Blood-Dark Track (30 page)

Authors: Joseph O'Neill

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Literary

My grandmother had been facing an ordeal of her own. Georgette Dakad was a strong woman – as a strong as a man, her friends used to say – but she was devastated by her husband’s disappearance; and things got no easier after 28 April 1942, when she gave birth to a third child, Amy. (Whom, in fact, she named Claude. When the little girl finally met her father at three and half years of age, she was renamed after a nurse who had been good to him. ‘Your name shall no longer be Claude,’ her father informed her. ‘You are Amy now.’) In their father’s absence, the three children grew up surrounded by women. Their grandmother, Teta, lived in the house, and their mother’s spinster sisters Isabelle and Alexandra were a constant presence. My mother said that she was a happy young child. When she grew old enough to ask about her father, she was told that Papa was away on a business trip. Then one day a spiteful girl said to her in the course of a kindergarten tiff about hopscotch, ‘At least

my

father isn’t in jail.’

Prices in Mersin were very high and Georgette was forced to make savings. The racehorse, Tayara, was sold, as was the shop in which the valuable hoard of tin had been secretly deposited by my

grandfather; and so (the story went) a fortune was mislaid. Georgette also had to take over the business of the Toros Hotel. This was not without its complications. The British, Mamie Dakad would later tell my mother, posted a spy in the hotel. Masquerading as a customer, he occupied the room near the office and stayed for some time, peeping and prowling around. One day, Georgette entered her office to discover that there had been a break-in. The safe was open, papers were scattered everywhere, but strangely the thousands of lira kept in the safe (a sum large enough to buy a property) were untouched. On another occasion, she was greeted on

the stairs of the hotel by an eminent Axis guest – the German or Italian ambassador, my mother thought – and she immediately went to the British consulate to report the encounter before they heard it from anyone else. Otherwise, Mamie Dakad effectively withdrew from society. She saw to the hotel in the mornings and stayed at home in the afternoons, when she would do housework and play cards with trusted girlfriends like Kiki and Dora and Lolo. According to Lolo, my grandmother was right to be cautious. The war split Mersin into factions, and a partisan or ambiguous gesture or flippant remark could lead to trouble with the Turkish authorities.

Georgette and Joseph, 1940. A family friend holds my infant mother.

In May 1943, the same month that Joseph Dakak was moved from the military hospital in Beirut to the monastery at Emuas, Denis Wright took over from Norman Mayers in Mersin. This was a significant development: according to my grandmother, Monsieur Wright helped her with sending and receiving letters, and he advised her not to invest hope and money in trying to secure her husband’s release but, rather, to await the end of the war. ‘I don’t remember giving her that advice,’ Wright said to me when I raised the subject, ‘but if I had advised her, that is the advice I would have given.’ ‘What do you remember?’ I asked. ‘I recall seeing her from time to time about her husband,’ Wright said. ‘I don’t recall much else.’ He added with a smile, ‘I take it you’ve read my letter about that party in Gözne.’

I had read it, in Wright’s volume of his letters home from Mersin. On the first weekend of September 1944, Wright went up to Gözne for ‘an end-of-season party arranged by the Vali but paid for by the Syrians’:

The Saturday evening dance took place in the garden of the coffee house: the Club orchestra was there and the refreshments were all prepared by the Syrians who complained that the Turkish women had done nothing to help with the fête.…

It was a rollicking party with a full moon shining down on us and all Gözne was there. The Syrians were as noisy as ever but seemed happier and less restrained in their own Gözne. I had a dance with Mme Dakad, the Toros Hotel woman whose husband is in one of our concentration camps in Syria or Palestine: it was the first time she had really amused herself in public since his arrest and the excitement of it all and the odd drinks she had had (and I gave her one which perhaps I shouldn’t have done) went to her head. She had a fit of crying and a sort of hysterics (by this time she had been removed from the dance floor to a room in the pub) shouting ‘

J’ai dansé avec M. Wright! Vive M. Wright! Vive le Consul d’Angleterre!

’ and repeating all this until she was forcibly taken home by Mme Carodi. She had recovered yesterday morning when I saw her playing poker – these Gözne Syrians play morning, afternoon and night daily and lose or win anything up to 300 liras a session, probably more. Mme Dakad has won about 3000 liras [about £410, which was more or less Wright’s annual salary] in the last few weeks, they say.

Denis Wright’s letters of the autumn of 1944 portrayed a more relaxed Mersin. The blackout was lifted, cricket matches were played at the ‘Braithwaites’ construction camp, and the consul represented Mersin in a tennis match. A jazz band played on the ‘millionairish’ seafront boulevard that was being built under the direction of the new Vali, Tewfik Gür. Jewish refugees bound for Cyprus passed through Mersin, and another excitement was the defection of an Austrian couple and a German who were working for German intelligence in Turkey – Herr and Frau von Kleckowski and Wilhelm Hamburgher. (The Americans had asked the British to smuggle them out of the country, and the trio stayed at the consulate before heading off to Syria on the Taurus Express.) Otherwise, life at the consulate passed quietly. On 11 November 1944, Mr Busk at the Ankara embassy noted, ‘The importance of Mersin has in the past lain in the fact that it was one of two accessible ports. We may hope that the Aegean will be shortly opened up and when this happens the importance of Mersin will sink to almost nothing.’

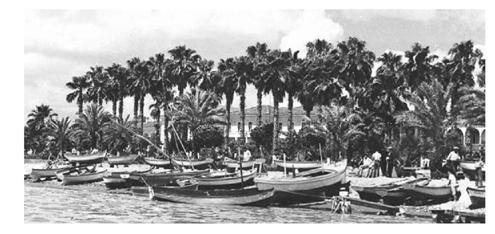

The old seafront at Mersin

And so, in January 1945, Denis Wright left Mersin for London. Before he left, he received a letter from my grandmother dated 9 January 1945 which he kept and later pasted in his album of memoirs. Mamie Dakad wrote (in French):

Mr Wright,

I have just learned of your departure and unfortunately there is not enough time to see you and thank you for all that you have been good enough to do for me. I hope that you will not forget me in Syria, because I must receive news from my husband.

Bon voyage and good luck.

Best wishes

G. Dakak

In May 1945, the European war ended. Still Georgette waited for her husband. Four months later, she was in the mountains, in Gözne, when she received a letter informing her of Joseph’s release. She was so absorbed by the letter that she didn’t notice a creature slithering in the vine overhead, and didn’t even flinch when the serpent suddenly fell and landed at her feet. My grandmother enjoyed telling her daughters this story, with its connotation of Eden regained.

T

he northern extremities of the Red Sea consist of two fingers of water that point, respectively, at the Mediterranean Sea and the Israel–Jordan border; and wedged between them is the triangle of the Sinai desert. The easternmost finger is the Gulf of Aqaba and at its very tip is the Israeli holiday destination of Eilat, a conglomeration of hotels, purpose-built lagoons and concrete apartment blocks generated by the proximity of coral reefs and submarine wildlife. I flew there from London on 7 April 1996, Easter Sunday. The British capital was passing through a tense, unpleasant phase, and I was glad to be leaving. A few days before, special stop and search laws, rushed through parliament that same week, had come into force: it was the eightieth anniversary of the Easter Rising, and intelligence reports suggested that the IRA planned to mark the occasion with violence. Londoners feared the worst. The IRA ceasefire had ended on 10 February with an explosion at South Quay, in the Docklands, in which hundreds had been injured and two killed. The city was subjected to further disruption and violence. Walking home one evening, I found that Soho was blocked off to traffic and that an ‘explosive device’ was being defused in a telephone booth I passed every morning on my way into work. Then, on Sunday 18 February, the 171 bus (which I used to take daily when I lived in south London) blew up at the Aldwych near Bush House, again at a place I walked by most working days. The explosion injured six and killed the carrier of the bomb, Eddie O’Brien, a twenty-one-year-old from Gorey, Co. Wexford. For a few days after, the spectacular carcass of the bus remained on the road, a fantastically mangled mass of strawberry metal coated with flakes of fine snow.

But the place I was flying into was far more dangerous than the one I was leaving. In nine days in February and March, Hamas suicide bombers had killed sixty-one people in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. These events triggered – as they were probably designed to – measures from the Israeli government that were as retaliatory as they were defensive, most notably the imposition of very strict restrictions on the movement of Arabs out of the West Bank and Gaza. With many thousands separated from their families and jobs,

the military and political crisis grew ever more bitter, and it seemed that further bomb attacks were imminent.

But there was no sign of trouble as I drove out of Eilat and across the stony heights and crumbling sandy hills of the Negev desert – only of ostriches, donkeys, camels and hovering hawks. I drove through Sodom and then, passing Masada, along the western shore of the Salt Sea into Judea. When the Salt Sea came to an end I turned westward; for some distance now (my map told me) I had been travelling in the Autonomous Territories. The desert was now freckled with bushes. Grazing lambs and nomad encampments appeared on the hills, and the roadside bloomed with poppies and shrubs with mustard- and lavender-coloured flowers. I passed through a couple of Israeli army checkpoints, and then, abruptly, I was in Jerusalem.

Jerusalem was more beautiful than I had ever imagined: a place of elevations and drops and, at its centre, where the walled Old City rose out of the green, bucolic depths of sheep-strewn valleys, extraordinary juxtapositions of pastoral and urban scenes. There was something else that I hadn’t anticipated. Because of planning regulations introduced by the British and evidently still in force seventy-five years later, buildings in the central districts of the city were constructed, or at least clad, in limestone, and as a consequence Jerusalem still presented to the world the pale stone exterior that used until a few decades ago to be so typical of the cities of the Levant. Ambling in tranquil, sunlit nineteenth-century districts in the New and Old Cities, I was overcome by visual and atmospheric echoes of old Mersin. It felt faintly absurd to apprehend the city in such humble terms, but as I walked amongst the dramatic throngs in the Old City – outlandishly outfitted monks and clerics, minuscule and bonneted old Greek women dressed entirely in black, East African pilgrims in long robes and turbans – and noted with amazement that the Arab, Christian, Jewish and Armenian quarters actually contained ancient populations of Arabs, Christians, Jews and Armenians (each attired in distinctive robes and hats and shawls), it occurred to me that this was precisely the vivid commingling of races and nationalities and religions and languages that

had so powerfully struck travellers to nineteenth-century Mersin. The link between this city and the little Turkish port of my childhood became clear: they were both profoundly Ottoman places. The gulf between modern, uniform Turkey and the culturally variegated Levant in which my grandfather grew up revealed itself. To trace his fate, I was beginning to realize, I needed to look deeper into that Ottoman world – in which, after all, Joseph Dakak had passed the first third of his life.

I stayed in the New Imperial Hotel, an attractive edifice in the Parisian style situated just by Jaffa Gate, in the Christian quarter of the Old City. Built in 1889 for Greek Orthodox pilgrims, the hotel was still the base for flocks of Greek women arriving for the Greek Orthodox Easter, who every morning and evening cawed and rustled in the hotel’s cavernous salon. There were remnants of the ‘Deli’ that used to operate here, and a sign persisted in proclaiming the availability of non-existent BEVERAGES! and SHAKES and DELI-SANDWICHES. On the balcony, lantern spheres advertised the croissants, brioches, cakes and ice-creams of yesteryear. The hotel motto – in English, like the other old signs – was painted on the wall of the ground floor entranceway:

Yesterday is already a dream and tomorrow is only a vision, but today well lived, makes every yesterday a dream of happiness and every tomorrow a vision of hope

.