Blood Brotherhoods (99 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

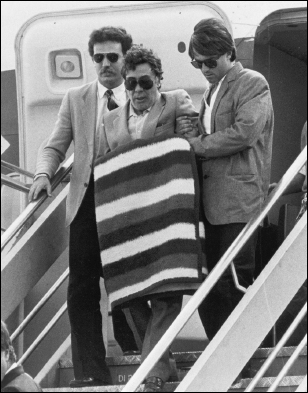

The most important informer in Italian underworld history. Cosa Nostra’s Tommaso Buscetta is brought back to Italy in 1984 after surviving a suicide attempt.

W

ALKING

C

ADAVERS

I

N HIS LAST INTERVIEW

, G

ENERAL

C

ARLO

A

LBERTO

D

ALLA

C

HIESA HAD SPOKEN ABOUT

the ‘fatal combination’ of being a danger to the mafia, and of being isolated. The same sense of isolation was articulated very clearly by one young magistrate based in Trapani, on the very western tip of Sicily. In 1982 a TV journalist provocatively asked him whether he was mounting a ‘private war’ against the mafia. The magistrate calmly explained that only certain magistrates would deal with mafia crime, and build up what he called a ‘historical memory’ about it. For that reason, what those few magistrates were doing in the public interest ended up looking like a private crusade. ‘Everything conspires to individualise the struggle against the mafia.’ And that, of course, is precisely how

mafiosi

themselves viewed the struggle: as a confrontation between Men of Honour and a few ball-breakers in the police and judiciary. For the

mafiosi

, the lines between private business and the public interest are simply invisible.

The young Trapani magistrate who made this point was a brusque, bespectacled classical music–lover called Gian Giacomo Ciaccio Montalto. One evening, only a few months after the interview, he and his white VW Golf were hosed with bullets. The street where he lay bleeding to death was a narrow one, and tens of people in the overlooking apartments must have heard the gunfire. Yet no one reported the incident until the following morning. Right up to its tragic conclusion, Ciaccio Montalto’s battle was an individualised one indeed.

As each ‘eminent corpse’ fell, seeming to confirm the mafia’s barbaric supremacy over Sicily, the tightly knit but isolated group of police and

magistrates who were fighting Cosa Nostra somehow found the will to carry on. One of the worst blows came in the summer of 1983 with the death of Falcone and Borsellino’s boss, the chief of the investigating magistrates’ office, Rocco Chinnici. Chinnici was murdered by a huge car bomb outside his house; two bodyguards and the janitor at the apartment block were also killed in the explosion. This was the most spectacular escalation yet of the Cosa Nostra’s terror campaign. Chinnici was one of the first magistrates to understand the importance of winning public support for the anti-mafia cause, of leaving the Palace of Justice to speak in public meetings and schools. His shocking death was intended to intimidate the whole island.

As one hero was cut down, another stepped in to take his place—a volunteer. Antonino Caponnetto was a quiet man, close to retirement, who gave up a prestigious job in Florence to return to his native Sicily. Before he even moved into the barracks that would be his Palermo home, Caponnetto knew what he wanted to do: adopt another lesson from the battle against terrorism in northern Italy. Faced with the daily threat of the Red Brigades, investigating magistrates had decided to work in small groups, or ‘pools’ (the English word was used), so that the elimination of one magistrate would not cripple a whole investigation. Caponnetto wanted to use the same method against the mafia. The Palermo anti-mafia pool—Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, along with Giuseppe Di Lello and Leonardo Guarnotta—would share the knowledge and the risks, uniting the different cases into a single great inquiry. The pool system was the magistrates’ response to the ‘fatal combination’.

The Palermo pool made steady progress. For example, Gaspare ‘Mr Champagne’ Mutolo’s phone was tapped, and the passages of his heroin trade with the Far East reconstructed. Mutolo’s supplier, Ko Bak Kin, was arrested in Thailand and subsequently agreed to come back to Italy to testify. Ballistic analysis had revealed that the same Kalashnikov machine gun was used in a whole series of mafia murders—from that of Stefano Bontate to General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa’s. The weapon was a common signature that began to make patterns discernible in the gore. Most importantly, the Flying Squad produced a report on 162

mafiosi

that included a rough sketch of the battle lines in the war that had led to the extermination of Stefano Bontate, Salvatore Inzerillo and their followers. But as yet, investigators were reliant on secret internal sources from the world of the mafia—men who were far too afraid, and far too mistrustful of the authorities, to give their names, let alone give evidence that could be used in court.

Then, in the summer of 1984, came Tommaso Buscetta, the boss of two worlds. The new penitent’s evidence marked a huge leap forward. Buscetta began from scratch by revealing the name that

mafiosi

used for their brotherhood. ‘The word mafia is a literary invention,’ Buscetta told Falcone. ‘This organisation is called “Cosa Nostra,” like in the United States.’

Buscetta’s interviews with Falcone carried on, almost without interruption, until January 1985. He revealed Cosa Nostra’s entire structure, naming everyone he could remember—from the soldiers at the bottom of the organisational pyramid, to the bosses of the Palermo Commission at the top. Drawing on nearly four decades of experience as a Man of Honour (he was initiated into the Porta Nuova Family in 1945), Buscetta taught Falcone about the exotic inner workings of the mafia world, its rituals, rules and mind-set. He identified culprits responsible for a host of murders. Still more importantly, he explained how those murders fitted into the strategic thinking of the bosses who had commissioned them. At last, the entire story of Shorty Riina’s rise to power in the Sicilian underworld made sense. The Sicilian mafia was not an unruly ensemble of separate gangs. It was Cosa Nostra: a unified, hierarchical organisation that had undergone a ferocious internal conflict.

Until now, Falcone and his colleagues had been examining the Sicilian mafia from the outside. It was as if they were trying to draw a floor plan of a building by peering in through the keyhole. Buscetta changed everything ‘by opening the door for us from the inside’, as Caponnetto would later recall. Falcone thought that Buscetta ‘was like a language professor who allows you to go to Turkey without having to communicate with your hands’. Following Buscetta’s example, more penitents would begin to talk. The most important of them was Totuccio Contorno, the soldier from Stefano Bontate’s Family who had narrowly survived a Kalashnikov attack in Brancaccio.

The pool managed to keep Buscetta’s collaboration a secret for months. Finally, on 29 September 1984, the secret could be kept no longer. Arrest warrants for 366

mafiosi

were put into effect at dawn: the operation became known as the St Michael’s Day blitz. The police ran out of handcuffs. And when the police’s work was done for the day, the pool held a press conference to proclaim to the world that the Sicilian mafia

as such

was to be brought before justice. Borrowing a word used to describe the massive prosecution of the Nuova Camorra Organizzata in Naples, the press began to talk about the forthcoming ‘maxi-trial’ in Palermo. In the streets where dialect was spoken, the trial became simply

’u maxi

. And the central issue in ‘the maxi’ would be Buscetta’s allegation—the ‘Buscetta theorem’, it was

dismissively labelled—that Cosa Nostra was a single, unified, hierarchical organisation.

The boss of two worlds was perfectly well aware of the historic scale of the trial that was being prepared around his testimony. Indeed a sense of his own historical mission was probably part of the mix of motives that led him to turn to Giovanni Falcone.

When the news first broke that Tommaso Buscetta was helping investigators, many commentators assumed that he was the first Sicilian

mafioso

to break the code of

omertà

. We now know more than enough about mafia history to be certain that Sicilian

mafiosi

have always talked. Both the winners and losers in the Sicilian underworld’s constant struggle for supremacy have broken

omertà

over the decades.

The winners talked in order to make a partnership with the police: in exchange for passing on information on their criminal competitors, they would be granted immunity from harassment. At a grassroots level, for the police or

Carabinieri

who demonstratively walked arm-in-arm around the piazza with the local boss, this arrangement guaranteed a quiet life. The Sicilian mafia specialised in a higher level of partnership with authority: when the mafia threatened to make Sicily ungovernable, ‘co-managing crime’ could become a cynical and covert official policy.

The mafia’s losers have broken

omertà

for a reason every bit as sordid: revenge. Abandoned by their powerful friends, out-fought and out-thought by their mafia rivals, they turned to the police as the instrument of vendetta, when no other instrument remained.

Tommaso Buscetta, like generations of

mafiosi

who broke the code of

omertà

before him, was a loser. He was part of the Transatlantic Syndicate that brokered narcotics between Sicily and the United States. As such, he felt the wrath of the

corleonesi

both before and after he decided to speak to Giovanni Falcone: between 1982 and 1984, no fewer than nine members of his family were killed, including two sons and a brother. The boss of two worlds, like many of the mafia’s losers before him, had many reasons to seek vengeance through the law. He was also like many mafia witnesses before him in that he told only a part of what he knew: his drug-trafficking friends were barely touched by his revelations.

Buscetta’s testimony also followed a script, a narrative about his personal journey that many other defeated

mafiosi

before him had recited. Once upon a time there was a good mafia, he claimed, a Cosa Nostra that adhered to the organisation’s true, noble ideals. Now Cosa Nostra had changed. Honour

was dead, and greed and brutality held sway. Now the mafia killed women and children—and so he, Tommaso Buscetta, as a true Man of Honour, would have nothing more to do with it. A misleading and self-interested tale, of course.

But if

mafiosi

have always talked, and Tommaso Buscetta was like the many

mafiosi

that had talked before him, why was he so important? Why is he always defined as the ‘history-making’ penitent? The main reason is that, whether the mafia reabsorbed them, intimidated them or simply killed them, mafia defectors rarely got to repeat their testimonies where it really counted: before a judge. What the prosecutors knew, they could not prove. When the mafia’s losers spoke, Italy refused to believe them. And a Sicilian elite that had been profoundly implicated with the killers of the mafia since Italy was unified needed no further invitation to bury what the mafia’s defectors said in verbiage: the mafia did not exist, they said; it was all a question of the Sicilian mentality, they said; all those rumours about a secret criminal association were the result of northern prejudices and paranoia; it was all the fault of Arab invaders, centuries ago.

Between talking to the police and testifying to a court, there was a long and difficult journey. For Falcone and the Palermo anti-mafia pool, the challenge was to help the boss of two worlds make it to the end of his journey. Only then could he really be said to have changed the course of history.

Falcone and Borsellino received crucial help in that task from the United States. The investigations into drug trafficking that had first drawn Falcone into the fight against the mafia had taught him just how profoundly linked, by both kinship and business ties, were

mafiosi

on both sides of the Atlantic. Falcone was a pioneer in grasping that anti-mafia investigators had to have the same, international outlook as their foe. Sicilian magistrates and police could make themselves twice as effective by seeking the help of their American counterparts. Buscetta, the boss of two worlds, was almost as important a witness in the United States as he was in Italy. And the United States, unlike Italy, had a proper witness-protection programme to which Buscetta could be entrusted.