Blood and Guts (29 page)

Authors: Richard Hollingham

With round-the-clock care in a specialist burns unit, Jacqui gradually

started to recover. Since September 1999 she has undergone

more than fifty operations. Surgeons have done their best to rebuild

her face; they even managed to restore an eyelid that had melted in

the blaze. But now they've reached the limits of traditional reconstructive

surgery and there is little more they can do. Jacqui's face

remains terribly disfigured. Her features are crumpled, her neck

sagging, her skin a blotchy, crinkled patchwork. She has no hair,

eyebrows or lashes. Her nose is flattened and distorted, her nostrils

drawn upwards. She has only the remains of a single ear, and her left

eye is swollen. Jacqui is still recovering from the events of 1999 and

has devoted her life to campaigning against drink-driving.

After examining cases like Jacqui's, plastic surgeons such as

Peter Butler believe that face transplants are the only way forward.

Butler is one of Britain's top plastic surgeons and uses imaging techniques

to simulate the effects of a face swap. On a computer screen

his team can virtually place one face over another. In theory, the

technical problems of a face transplant have already been overcome.

The surgery is perfectly possible, although the cocktail of

drugs to prevent rejection would probably take ten years off a

patient's life. However, there are big ethical questions over whether

it is right to take the face of one person and transplant it on to

another. Our faces define us – how would a new face change us?

And what about the donor family – how would they react to seeing

the face of a loved one on somebody else's body?

Plastic surgery has come a long way since the brutal operations

conducted in early India, or Tagliacozzi's leather corset and pedicle.

The real triumph of plastic surgery has not been the cosmetic

surgery for the 'beauty cranks' – the botox, the silicone or the facelifts

– but the effort that has gone into fixing terribly damaged faces.

Over the centuries surgery has restored the faces of syphilis

victims, soldiers, airmen and the victims of fire or car crashes. Today

surgeons can save the lives of even the most badly burnt and injured

patients, such as Jacqueline Saburido, but despite all the advances in

modern medicine they can only do so much.

Soon (possibly by the time this book is published) someone in

the world will have received the first full-face transplant. You can bet

the story will be a sensation. However, advances in tissue engineering

will eventually enable surgeons to grow swathes of skin in the

lab. They have already been able to grow a human ear on the back

of a mouse. One day it might even be possible to construct an entire

new face from samples of a patient's own DNA. We can only hope

that the technology is used to reconstruct the faces of the victims

of conflict or tragedy rather than to boost the vanity of ageing

Hollywood stars, Page 3 models or the Gladys Deacons of this world.

Tagliacozzi's 16th-century jacket-and-strap arrangement.

You can see the pedicle linking the patient's upper arm and face.

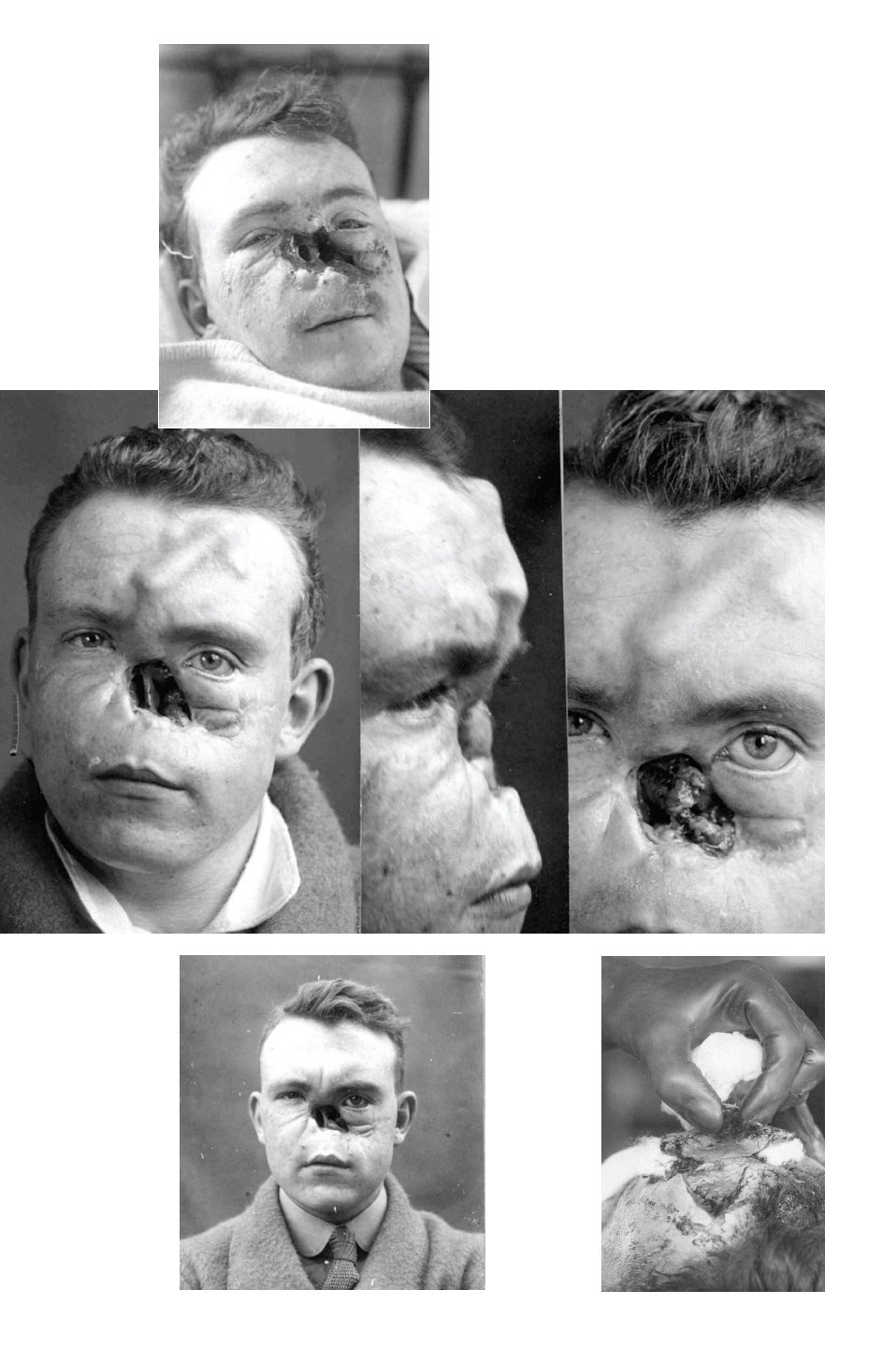

Rebuilding the face of

William Spreckley during the First World

War. The second picture shows the arrowshaped

piece of cartilage implanted

under the skin of Spreckley's forehead.

Looking at the final picture, it is hard

to believe that Spreckley was once

without a nose.

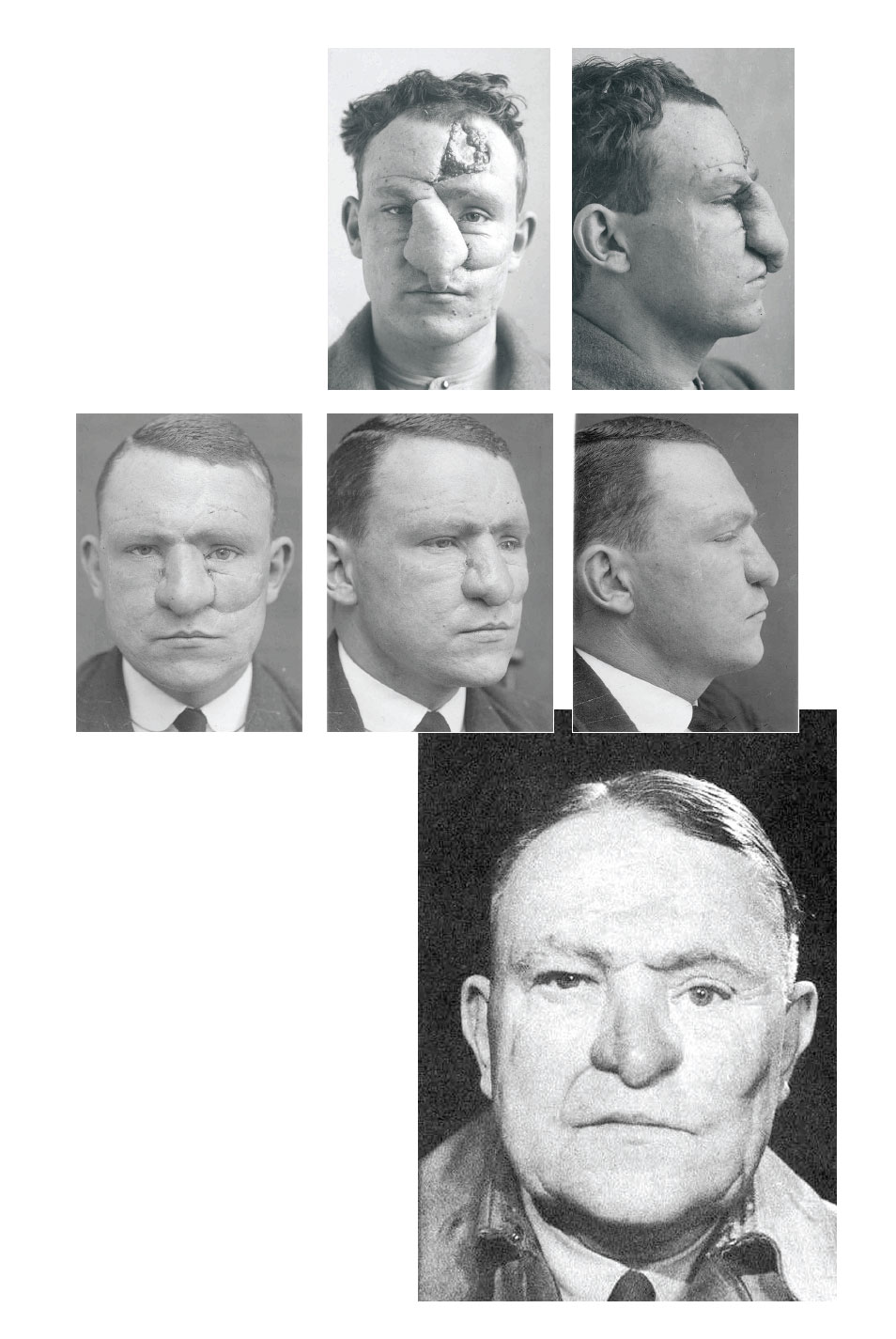

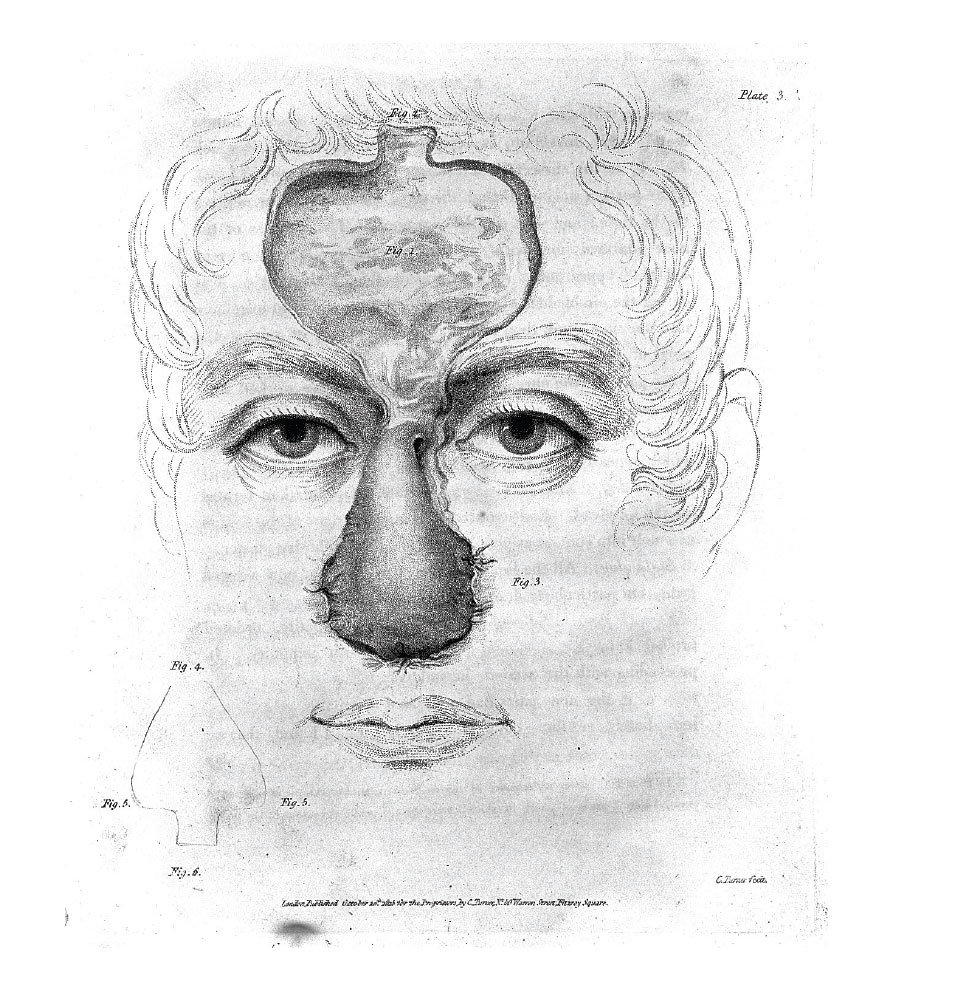

Drawing of an

early 19th-century

operation for 'restoring'

the nose. Although crude,

these procedures were

often successful.

Four members of

the Guinea Pig Club in

their ward at East Grinstead

in the 1940s. They are all

sporting tube pedicles

showing the intermediate

stages of facial

reconstruction.

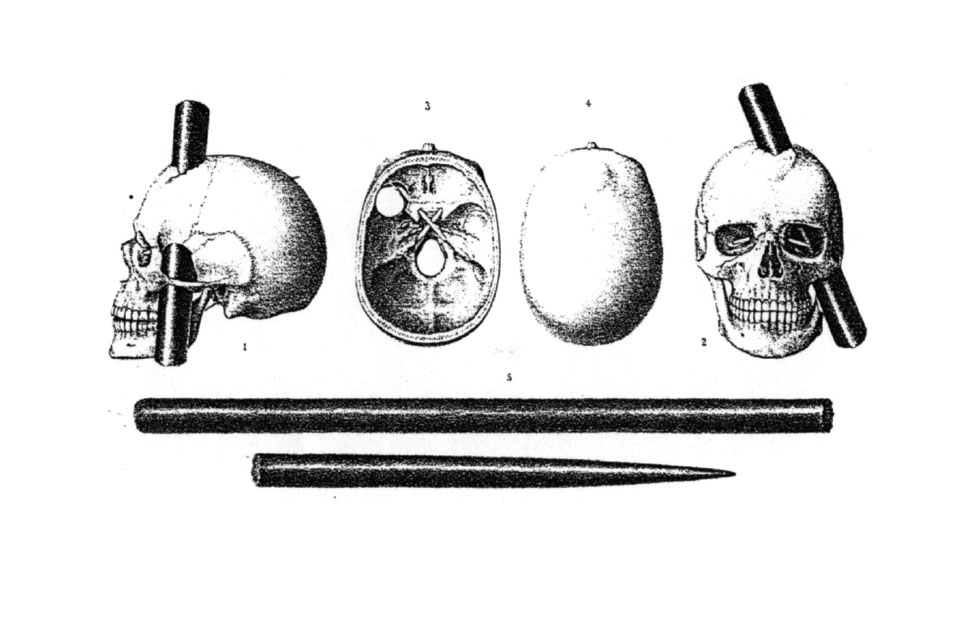

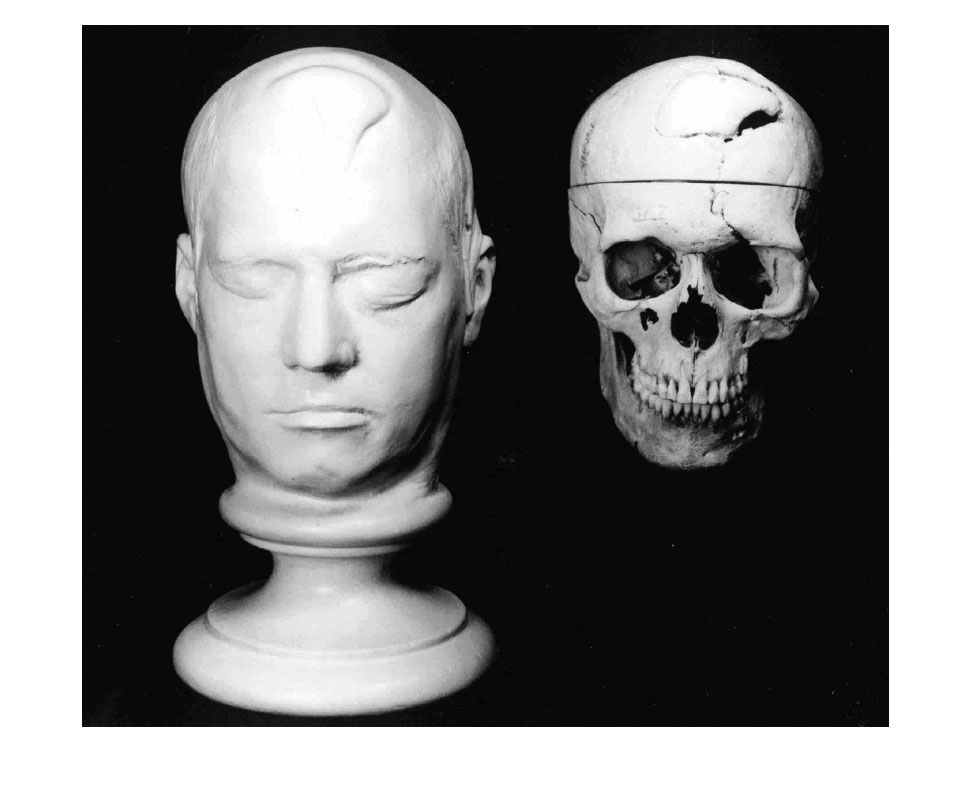

An 1850 interpretation of the passage of the

tamping iron through Phineas Gage's skull.

A mask made of Phineas Gage's face (probably when

he was still alive) pictured next to the railroad worker's skull.

The partially healed hole can be seen clearly on the top.

Another day at the office for lobotomist Walter

Freeman as he performs his procedure in front of a

fascinated audience. This picture dates from 1949, before

lobotomies became completely discredited.

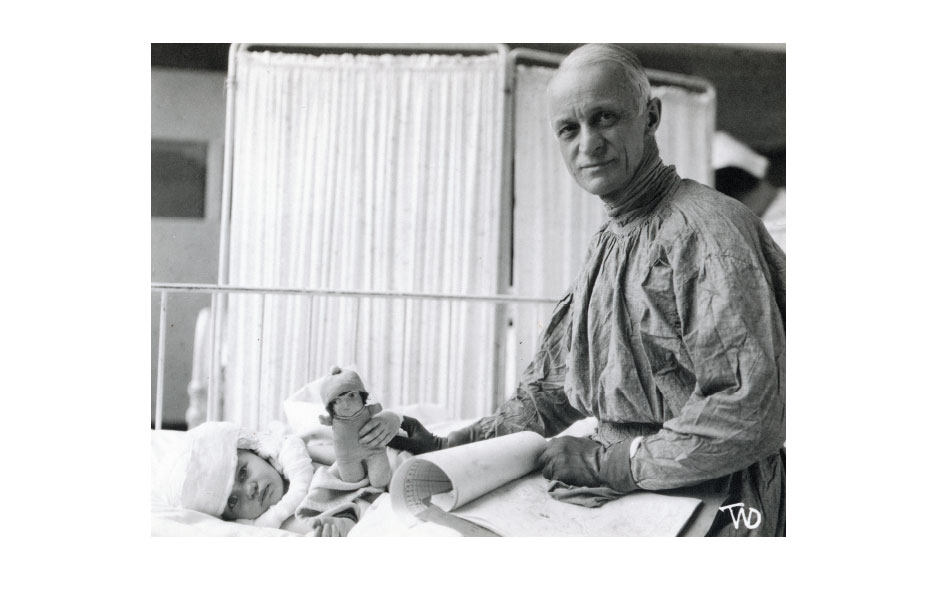

Harvey

Cushing, the

brilliant, god-like

surgeon who was

adored by his

patients.

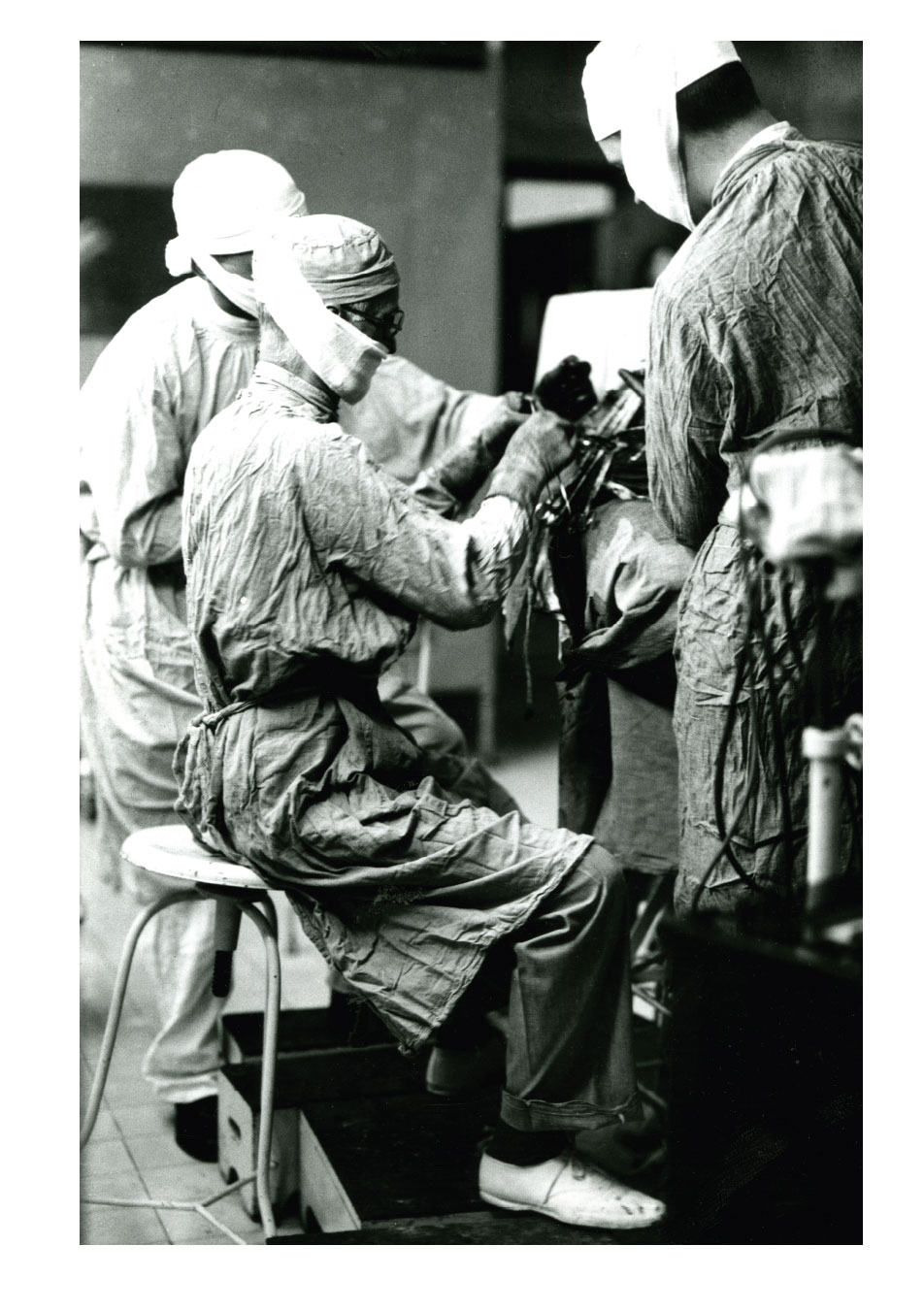

Harvey Cushing operating on his 2000th brain tumour

in 1931. During his impressive career, Cushing would save

hundreds of lives and transform brain surgery.