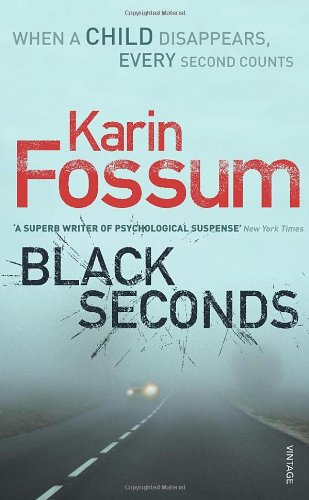

Black Seconds

Authors: Karin Fossum

Karin Fossum made her literary debut in Norway in 1974. The author of poetry, short stories and one noncrime novel, it is with her Inspector Sejer Mysteries that she has won great acclaim. The series has been published in sixteen languages.

Charlotte Barslund translates Scandinavian novels and plays. Her recent work includes

Calling Out For

You

by Karin Fossum,

Machine

by Peter Adolphsen and

The Pelican

by August Strindberg.

Don’t Look Back

He Who Fears the Wolf

When the Devil Holds the Candle

Calling Out For You

Black Seconds

TRANSLATED FROM THE NORWEGIAN BY

Charlotte Barslund

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Adobe ISBN: 9781407017358

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Vintage 2008

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright © Karin Fossum 2002

English translation copyright © Charlotte Barslund 2007

Karin Fossum has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

First published with the title

Svarte Sekunder

in 2002 by J. W. Cappelens Forlag A.S., Oslo

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by Harvill Secker

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

www.vintage-books.co.uk

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

This edition was published with the financial assistance of

The Random House Group Limited supports The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the leading international forest certification organisation. All our titles that are printed on Greenpeace approved FSC certified paper carry the FSC logo. Our paper procurement policy can be found at www.rbooks.co.uk/environment

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

CPI Bookmarque, Croydon CR0 4TD

TO ØYSTEIN, MY YOUNGER BROTHER

The days went by so slowly.

Ida Joner held up her hands and counted her fingers. Her birthday was on the tenth of September. And it was only the first today. There were so many things she wanted. Most of all she wanted a pet of her own. Something warm and cuddly, which would belong only to her. Ida had a sweet face with large brown eyes. Her body was slender and trim, her hair thick and curly. She was bright and happy. She was just too good to be true. Her mother often thought so, especially whenever Ida left the house and she would watch her daughter’s back disappear around the corner. Too good to last.

Ida jumped up on her bicycle, her brand-new Nakamura bicycle. She was going out. The living room was a mess: she had been lying on the sofa playing with her plastic figures and several other toys, and it was chaos when she left. At first her absence would create a great void. After a while a strange mood would creep in through the walls and fill the house with a sense of unease. Her mother hated it. But she could not keep her daughter locked 1

up for ever, like some caged bird. She waved to Ida and put on a brave face. Lost herself in domestic chores. The humming of the Hoover would drown out the strange feeling in the room. When her body began to grow hot and sweaty, or started to ache from beating the rugs, it would numb the faint stabbing sensation in her chest which was always triggered by Ida going out.

She glanced out of the window. The bicycle turned left. Ida was going into town. Everything was fine; she was wearing her bicycle helmet. A hard shell that protected her head. Helga thought of it as a type of life insurance. In her pocket she had her zebra-striped purse, which contained thirty kroner about to be spent on the latest issue of

Wendy

. She usually spent the rest of her money on Bugg chewing gum. The ride down to Laila’s Kiosk would take her fifteen minutes. Her mother did the mental arith metic. Ida would be back home again by 6.40 p.m. Then she factored in the possibility of Ida meeting someone and spending ten minutes chatting. While she waited, she started to tidy up. Picked up toys and figures from the sofa. Helga knew that her daughter would hear her words of warning

wherever she went. She had planted her own voice of authority firmly in the girl’s head and knew that from there it sent out clear and constant instructions. She felt ashamed at this, the kind of shame that overcomes you after an assault, but she did not dare do otherwise. Because it was this very voice that would one day save Ida from danger. 2

Ida was a well-brought-up girl who would never cross her mother or forget to keep a promise. But now the wall clock in Helga Joner’s house was approach ing 7 p.m. and Ida had still not come home. Helga experienced the first prickling of fear. And later that sinking feeling in the pit of her stomach that made her stand by the window from which she would see Ida appear on her yellow bicycle any second now. The red helmet would gleam in the sun. She would hear the crunch of the tyres on the pebbled drive. Perhaps even the ringing of the bell: hi, I’m home! Followed by a thud on the wall from the handlebars. But Ida did not come. Helga Joner floated away from everything that was safe and familiar. The floor vanished beneath her feet. Her normally heavy body became weight

less; she

hovered like a ghost around the rooms. Then with a thump to her chest she came back down. Stopped abruptly and looked around. Why did this feel so familiar? Because she had already, for many years now, been rehearsing this moment in her mind. Because she had always known that this beautiful child was not hers to keep. It was the very realisation that she had known this day would come that terrified her. The knowledge that she could predict the future and that she had known this would happen right from the beginning made her head spin. That’s why I’m always so scared, Helga thought. I’ve been terrified every day for nearly ten years, and for good reason. Now it’s finally hap

pened. My worst nightmare.

Huge, black, and tearing my heart to pieces. 3

It was 7.15 p.m. when she forced herself to snap out of her apathy and find the number for Laila’s Kiosk in the phone book. She tried to keep her voice calm. The telephone rang many times before someone answered. Her phoning and thus

revealing her fear made her even more convinced that Ida would turn up any minute now. The ulti mate proof that she was an overprotective mother. But Ida was nowhere to be seen, and a woman answered. Helga laughed apologetically because she could hear from the other woman’s voice that she was mature and might have children of her own. She would understand.

‘My daughter went out on her bicycle to get a copy of

Wendy

. From your shop. I told her she was to come straight back home and she ought to be here by now, but she isn’t. So I’m just calling to check that she did come to your shop and bought what she wanted,’ said Helga Joner. She looked out of the window as if to shield herself against the reply.

‘No,’ the voice answered. ‘There was no girl here, not that I remember.’

Helga was silent. This was the wrong answer. Ida had to have been there. Why would the woman say no? She demanded another reply. ‘She’s short with dark hair,’ she went on stubbornly, ‘nine years old. She is wearing a blue tracksuit and a red helmet. Her bicycle’s yellow.’ The bit about the bicycle was left hanging in the air. After all, Ida would not have taken it with her inside the kiosk.

4

Laila Heggen, the owner of the kiosk, felt anxious and scared of replying. She heard the budding panic in the voice of Ida’s mother and did not want to release it in all its horror. So she went through the last few hours in her mind. But even though she wanted to, she could find no little girl there. ‘Well, so many kids come here,’ she said. ‘All day long. But at that time it’s usually quiet. Most people eat between five and seven. Then it gets busy again up until ten. That’s when I close.’ She could think of nothing more to say. Besides, she had two burgers under the grill; they were beginning to burn, and a customer was waiting.

Helga struggled to find the right words. She could not hang up, did not want to sever the link with Ida that this woman embodied. After all, the kiosk was where Ida had been going. Once more she stared out into the road. The cars were few and far between. The afternoon rush was over.

‘When she turns up,’ she tried, ‘please tell her I’m waiting.’

Silence once again. The woman in the kiosk wanted to help, but did not know how to. How awful, she thought, having to say no. When she needed a yes.

Helga Joner hung up. A new era had begun. A creeping, unpleasant shift that brought about a change in the light, in the temperature, in the land scape outside. Trees and bushes stood lined up like militant soldiers. Suddenly she noticed how the sky, which had not released rain for weeks, had filled 5

with dark, dense clouds. When had that happened?

Her heart was pounding hard and it hurt; she could hear the clock on the wall ticking mechanically. She had always thought of seconds as tiny metallic dots; now they turned into heavy black drops and she felt them fall one by one. She looked at her hands; they were chapped and wrinkled. No longer the hands of a young woman. She had become a mother late in life and had just turned forty-nine. Suddenly her fear turned into anger and she reached for the tele phone once more. There was so much she could do: Ida had friends and family in the area. Helga had a sister, Ruth, and her sister had a twelve-year-old daughter, Marion, and an eighteen-year-old son, Tomme, Ida’s cousins. Ida’s father, who lived on his own, had two brothers in town, Ida’s uncles, both of whom were married and had four children in total. They were family. Ida could be with any of them. But they would have called. Helga hesitated. Friends first, she thought. Therese. Or Kjersti, perhaps. Ida also spent time with Richard, a twelveyear-old boy from the neighbourhood, who had a horse. She found the contact sheet for her daughter’s classmates stuck on the fridge, it listed everyone’s name and number. She started at the top with Kjersti.

‘No, sorry, Ida’s not here.’ The other woman’s concern, her anxiety and sympathy, which con cluded with the reassuring words, ‘She’ll turn up, you know what kids are like,’ tormented and haunted her.

6

‘Yes,’ Helga lied. But she did not know. Ida was never late. No one was home at Therese’s. She spoke to Richard’s father, who told her his son had gone down to the stable. So she waited while he went to look for him. The clock on the wall mocked her, its constant ticking: she hated it. Richard’s father came back. His son was alone in the stable. Helga hung up and rested for a while. Her eyes were drawn to the window as if it were a powerful magnet. She called her sister and crumbled a little when she heard her voice. Could not stand upright any longer, her body was beginning to fail her, paralysis was setting in.

‘Get in your car straight away,’ Ruth said. ‘Get yourself over here and together we’ll drive round and look for her. We’ll find her, you’ll see!’

‘I know we will,’ Helga said. ‘But Ida doesn’t have a key. What if she comes back while we’re out looking for her?’

‘Leave the door open. It’ll be fine, don’t you worry. She’s probably been distracted by some thing. A fire or a car crash. And she’s lost track of time.’

Helga tore open the door to the garage. Her sister’s voice had calmed her down. A fire, she thought. Of course. Ida is staring at the flames, her cheeks are flushed, the firemen are exciting and appealing in their black uniforms and yellow helmets, she is rooted to the spot, she is bewitched by the sirens and the screaming and crackling of the flames. If there really was a fire, I too would be 7

standing there mesmerised by the shimmering heat. And besides, everything around here is like a tinder box, it hasn’t rained for ages. Or a car crash. She fumbled with her keys while she conjured up the scene. Images of twisted metal, ambulances, resusci tation efforts and spattered blood rushed through her mind. No wonder Ida had lost track of time!

Distracted, she drove to her sister’s house in Madseberget. It took four minutes. She scanned the verges the whole time; Ida was likely to appear without warning, cycling on the right-hand side of the road as she should, carefree, safe and sound. But she did not see her. Still, taking action felt better. Helga had to change gears, steer and brake; her body was occupied. If fate wanted to hurt her, she would fight back. Fight this looming monster tooth and nail.