Beyond the Sky and the Earth (15 page)

Read Beyond the Sky and the Earth Online

Authors: Jamie Zeppa

It occurs to me now that in Sharchhop, the same word is used for both “thrown out” and “lost,” and there is no distinction between “to need” and “to desire.” If something is thrown out, it is lost to further use, and if you want something here, you probably also need it. When I study my Sharchhop book, I wonder who is richer, who poorer. English has so many words that do not exist in Sharchhop, but they are mostly nouns, mostly things: machine, airplane, wristwatch. Sharchhop, on the other hand, reveals a culture of material economy but abundant, intricate familial ties and social relations. People cannot afford to make a distinction between need and desire, but they have separate words for older brother, younger sister, father’s brother’s sons, mother’s sister’s daughters. And there are two sets of words: a common set for everyday use and an honorific one to show respect. There are three words for gift: a gift given to a person higher in rank, a gift to someone lower, and a gift between equals.

In the village, few written records are kept, but everyone knows who is related to whom, why that person left the village, what inauspicious signs shone down as they set out, what illnesses and misfortunes befell them after, what offerings were made, what consolation followed. Here the world is still small enough that knowledge is possible without surnames, records, certificates of birth and death. The world is that small, and yet it seems vaster to me, bigger and older and more complex than my world in Canada, where there is an official version of every life and death, and history is lopped and fitted and trimmed into chapters, and we read it once or twice and forget. It is written down; there is no need to remember. There is no need to remember, hence we forget. Whereas here history is told so that it can be remembered, it is remembered because it is told. The Sharchhop word for “history” translates into “to tell the old stories.”

Back at home, I collect my two buckets of rainwater from below the eaves. The tap water has been off for two days, but the rain has been plentiful. I am managing. In the evening, I am surprised by the sound of a vehicle outside my window. A white hi-lux has wedged itself in front of the building, and boxes, crates and tins are being unloaded onto the muddy ground. My Australian neighbor, I think, and it is. He knocks on the door later, a man with tufts of greying hair standing on end and a big grin. He introduces himself as Trevor and starts handing things over. He has brought my tin and a note from Sasha, bread from Thimphu, Swiss-made cheese from Bumthang, peaches and plums from Tashigang, and letters from home that ended up at the field office. I start to help him cart his luggage up the stairs but he waves me away. “Go read your mail,” he says kindly. I tear open the envelopes and read hungrily. Then I put my groceries away, arranging things carefully on the shelves. I feel immensely rich and unaccountably lucky, as if I had just won a lottery.

At my desk, I start a letter to Robert about the difference between arrival and entrance. Arrival is physical and happens all at once. The train pulls in, the plane touches down, you get out of the taxi with all your luggage. You can arrive in a place and never really enter it; you get there, look around, take a few pictures, make a few notes, send postcards home. When you travel like this, you think you know where you are, but, in fact, you have never left home. Entering takes longer. You cross over slowly, in bits and pieces. You begin to despair: will you ever get over? It is like awakening slowly, over a period of weeks. And then one morning, you open your eyes and you are finally here, really and truly here. You are just beginning to know where you are.

I write about all the things I have learned. Mustard oil must be heated until it smokes before you fry anything in it. Climbing a mudslide is easier barefoot. Water has a lower boiling point at high altitudes. Now I am knowing, as my students would say. All my former knowledge and accomplishments seem useless to me now—all the critical jargon I carry around in my head, tropes and modes and traces, thirteen definitions of irony, the death of the author, the anxiety of influence, there is nothing outside the text. So what? That doesn’t help me in the least now. Let Jacques Derrida come here, I think. Let him stay up half the night scratching flea bites and then deconstruct the kerosene stove before breakfast. I have had to learn everything all over again, how to walk without falling headlong into bushes, how to clean rice, how to chop chilies without rubbing my hand in my eye and blinding myself. Eight year olds have had to take care of me. My ignorance amazes me.

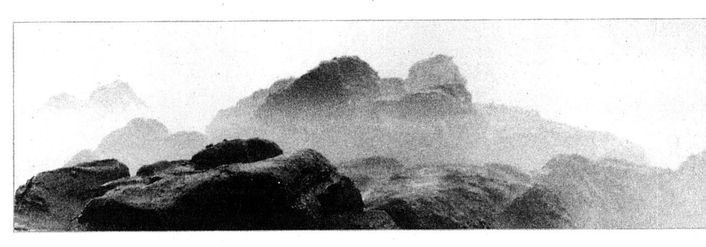

Now when I long for the small comforts of my Canadian life, I remind myself that someday I will be home, longing perhaps for the misted view of mountains from my bedroom window, the smell of woodsmoke, a room lit by candlelight, the sound of rain moving into the valley. The rain has stopped, and the clouds are shifting to reveal a sharp, thin crescent moon and one bright star. It’s the kind of moon you can climb into, a silver boat, a rocking chair. Robert, I write, I am just beginning to realize where I am.

Movement Order

Early in June, the

rains set in, and

were so constant

that ... there

generally fell a

shower in some part

or other of the

twenty-four hours,

and the tops of the

hills were constantly

involved in clouds.

rains set in, and

were so constant

that ... there

generally fell a

shower in some part

or other of the

twenty-four hours,

and the tops of the

hills were constantly

involved in clouds.

—

Samuel Davis

in Bhutan, 1783

Samuel Davis

in Bhutan, 1783

Rangthangwoong

T

he start of a three-day holiday, and I have a list of things to do: get rid of the rat in the kitchen without the aid of the trap that so horrified my students (oh miss, they told me, you is killing this rat, then you is coming back as rat for many lifes), fix the screens that let in a thousand flies a day (the same karmic rule applies to killing flies), bake bread using the old pot-in-the-pot-on-the-kerosene-stove method. But then Trevor knocks on my door to say that he is going up to Tashigang for the weekend and do I want to go. I stuff a toothbrush and a clean tee shirt into my jhola and race down the stairs to where the hi-lux is coughing up a cloud of gritty smoke.

he start of a three-day holiday, and I have a list of things to do: get rid of the rat in the kitchen without the aid of the trap that so horrified my students (oh miss, they told me, you is killing this rat, then you is coming back as rat for many lifes), fix the screens that let in a thousand flies a day (the same karmic rule applies to killing flies), bake bread using the old pot-in-the-pot-on-the-kerosene-stove method. But then Trevor knocks on my door to say that he is going up to Tashigang for the weekend and do I want to go. I stuff a toothbrush and a clean tee shirt into my jhola and race down the stairs to where the hi-lux is coughing up a cloud of gritty smoke.

Tashigang has grown somehow in two months, I think, as we pull into the center of town between a bus that is disgorging an endless stream of stiff-limbed, dazed passengers and a truck loaded with crates. It seemed so small and medieval when we drove through in March. I took no account then of the tarmacked roads, the electricity wires, the number of buildings—bank, hospital, telephone exchange, barber, tailor, post office, hydropower cell, wireless station, school, police headquarters, petrol station, bars, bars-cum-hotels. I didn’t notice the hand-drawn AIDS poster on a shop wall. I didn’t notice you could buy shoes in Tashigang. And shoe polish, playing cards, colored markers, curtain rings and hair dye. I didn’t notice you could buy so many things you didn’t actually need.

Two Westerners are sitting on a bench outside the Puen Soom, and although it has been months since I met them in Thimphu, I recognize them instantly. Leon, posted in Wamrong, and Tony from Khaling, are in the second year of their contracts. They are both tall and blond and very thin, but in their faded cotton clothes and rubber flip-flops, with colorful jholas at their feet, they do not seem out of place. They are reading and sipping glasses of murky liquid. Mud puppies, they inform me, sweet tea with a shot of Dragon Rum. Tomorrow they are going to visit Catherine, the Canadian teacher in Rangthangwoong, and they invite me to come along. I hesitate. I don’t want to miss my ride back to Pema Gatshel with Trevor tomorrow, but when will I get another chance to go to what-was-it-called again? I decide to go.

Leon and Tony are staying with Kevin, another Canadian teacher posted in Tashigang. “Is there room for me, or should I stay in a hotel?” I ask.

“Which hotel would that be?” Leon asks, gesturing grandly at the bazaar. “Bedbug Inn? The Flea Seasons?”

“This is eastern Bhutan,” Tony says. “Where there’s a floor, there’s room.”

On the way up to Kevin’s house, we stop at a bakery to buy soft, flat rounds of Tibetan bread. On one wall are somber black-and-white photographs of the four kings of Bhutan and a religious calendar from last year, the Year of the Earth Dragon. On the wall opposite is a poster of a scarlet-lipped, dagger-nailed Joan Collins. No one seems to mind the incongruity.

Kevin lives in a concrete block of a house furnished with the usual wooden benches and stiff chairs. We sit in the kitchen, drinking beer, peeling vegetables for dinner and sharing reports on the lateral road, the mail situation, and the state of everyone’s health—who got what from where and what they did about it. I laugh until my throat hurts. A leech up the nose wouldn’t have seemed so funny three months ago.

Outside, shadows collect under the eucalyptus trees and the air is filled with birdsong and the whistling of pressure cookers as neighbors prepare their evening meals. Inside, I find the electric lights harsh and strangely wasteful. I am used to having a circle of warm light only where I need it; I feel out of sync with the growing twilight outside and keep checking my watch. Leon and Tony have brought sleeping bags; I borrow a blanket from Kevin and lay some cushions down on the floor. It is nine o’clock and Tashigang is still awake: Bhutanese folk music drifts up from the bazaar, a vehicle honks impatiently, trucks lumber up the road, a woman yells repeatedly for Sonam to come home. Eventually, the sounds begin to fade away, Sonam finally comes home and even the thriving metropolis of Tashigang goes to sleep.

The bus to Rangthangwoong turns out to be a truck. We squeeze ourselves into the open back and wait for the driver. People keep climbing in, and soon I must balance awkwardly on one foot until my other foot finds a tentative resting place on a sack of rice. The engine grunts and wheezes to life and the truck lurches off down to the river, over the bridge called Chazam, and onto a rough, dusty road. The landscape is dry and sun-bleached, with chir pine trees dotting the dry, rocky slopes, a complete contrast to the wet, dense green of the enclosed Pema Gatshel valley. I turn my face into the hot wind and the girl next to me smiles and admires my silver earrings. She looks about fifteen, and has a pretty, heart-shaped face. Her earrings are thick, hand-fashioned hoops of gold. “Yours are nicer,” I tell her in Sharchhop. She shakes her head shyly. A group of students in their school ghos and kiras begins to sing. A man in a blue-striped gho, smelling strongly of arra, lurches against us when the truck turns a sharp corner and stops. We are at Duksam, two rows of crooked wooden shops along a narrow tarmacked road; several passengers leap out, several more leap on.

When the bus starts up again, I notice the man in blue has pushed himself between me and the girl. He is singing loudly as he clamps his hand over the girl’s breast. She looks away but there is no place for her to move. I cannot read her expression. I don’t know what to do, if I should do anything. Part of me is thinking, this is not your culture. You’ve been here for a few short weeks, you don’t even speak the language. You don’t know what’s going on here, who are you to interfere? The other part of me is thinking, it is perfectly clear what is going on here. It is not a matter of cultural differences. But it cannot be

perfectly clear,

except to a Bhutanese, and I am profoundly unsure, paralyzed by this inner argument. Finally, I work my way between the man and the girl. When he tries to reach around me, I elbow away his hand, and he looks into my face, puzzled. I look straight back. The singing around us has stopped. The man grins and shrugs and turns away. I try to look at the girl, but she is looking straight ahead and will not meet my eye. I can only hope I have done the right thing.

perfectly clear,

except to a Bhutanese, and I am profoundly unsure, paralyzed by this inner argument. Finally, I work my way between the man and the girl. When he tries to reach around me, I elbow away his hand, and he looks into my face, puzzled. I look straight back. The singing around us has stopped. The man grins and shrugs and turns away. I try to look at the girl, but she is looking straight ahead and will not meet my eye. I can only hope I have done the right thing.

Rangthangwoong is halfway up a mountain, a village scattered around three large houses with ground-floor shops. Catherine is dressed in a grey kira, but her bright auburn hair sets her apart in the crowd waiting for the bus. Her quarters, located above one of the shops, consist of a bed-sitting room and, across a communal hallway, a bathroom and kitchen. She has been here for two years already, and she is very excited because the landlord has just installed a tap in her kitchen. We go to admire it, turning it on and off, laughing at ourselves. Someone has brought her a bottle of fresh buttermilk, and she pours us each a cup and then we walk up to the ruins of a ninth-century castle. Sitting below, on a grassy knoll, Catherine points to a mountain at the end of the valley. “That’s India,” she says. “The town is Tawang, in Arunachal Pradesh. At night, we can see the lights. My headmaster says you could walk there in one day.” This, of course, is illegal, she adds. You would run into the army at the border. This is where the Indo-China war spilled over into Bhutan in 1962. After the Chinese invasion of Tibet, India began to station troops along the northern frontier, including along Bhutan’s northern borders. The brief war was the result of growing tension along the northeastern Indian border, with both China and India claiming the area as their own. The older people still talk about it, Catherine says, the sudden appearance of helicopters in the sky over a village that had never even seen a vehicle. They thought it was the end of the world.

Other books

Wolf Claim (Wolves of Willow Bend Book 3) by Long, Heather

The Burning Shadow by Michelle Paver

Rocky Mountain Rose (Rocky Mountain Bride Series Book 3) by Lee Savino

Daphne by Beaton, M.C.

Lightning Strikes Part 2 (36 Hours) by Baxter, Mary Lynn

Wars of the Irish Kings by David W. McCullough

Love In Alabama (The Love In Series Book 1) by Shelby Gates

There's Something About Lady Mary by Sophie Barnes

No Horse Wanted by Melange Books, LLC