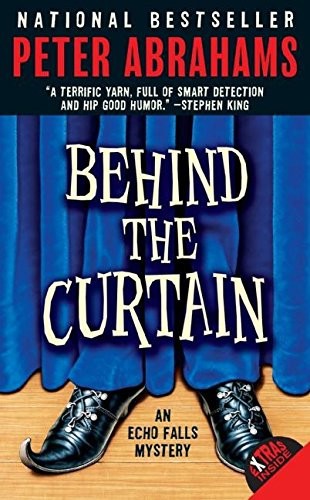

Behind the Curtain

Read Behind the Curtain Online

Authors: Peter Abrahams

Behind the Curtain

An Echo Falls Mystery

To Rick Starke

INGRID LEVIN-HILL SAT in math class, her mind wandering pleasantly.

“ANYONE SEEN The Echo?” Mom said, setting the takeout cartons…

INGRID HAD HEALTH last period on Fridays. Time slowed way,…

INGRID HAD A DREAM she dreamed over and over, all…

FINAL SCORE: ECHO FALLS 2, South Harrow 1. Should have…

SOMETHING TO EAT turned out to be dinner in the…

“PHONE.”

“HI, GRAMPY,” INGRID said through the open window of the…

TUESDAY, A DAY OF the week Ingrid would just as…

INGRID LAY ON HER BED, reading from The Complete Sherlock…

INGRID AWOKE IN THE night. She wasn’t used to all…

SOMETIME LATE FRIDAY night or early Saturday morning, Ingrid dreamed…

“THIS CHILD,” SAID MS. Groome, “has a rather wild story…

“SHE WANTS TO GO to soccer,” Mom said.

IM-ING, SUNDAY NIGHT.

“YOU MUST BE INGRID,” said Dr. Josef Vishevsky.

“Coffee?” Mom said.

“I PLAYED HOOKY ALL THE time,” said Julia LeCaine.

“SPYING ON YOU, GRAMPY?” Ingrid said. “I don’t understand.”

NO ONE HOME: TY still at practice, Mom and Dad…

INGRID WALKED ALONG the basement corridor in Echo Falls High.

“HOW WAS REHEARSAL?” Mom said, looking up from a set…

A REAL BIG STORM, BUT Ingrid’s snug little boat was…

MOM AND DAD BOTH came home before five, very unusual.

SUNDAY MORNING, breakfast at the Rubinos’. Sausages, ham, eggs, pancakes…

FROM The Echo:

AFTER SCHOOL ON Wednesday: last soccer practice before Saturday’s championship…

AND THEN JULIA’S face was gone.

CHIEF STRADE TOOK JOEY and Ingrid to Benito’s, best pizza…

I

NGRID

L

EVIN

-H

ILL SAT

in math class, her mind wandering pleasantly. She had the best seat in the house—very back of the outside row by the windows, about as far as could be from the teacher, Ms. Groome. Ferrand Middle School stood on a hill overlooking the river, about a mile upstream from the falls. There was always something interesting to see on the river, especially if you were in the habit of noticing little details. Little details like how the water ruffled up as it flowed around a rock, and a big black bird drifting on the current, wings tucked under its chin, and—

“Ingrid? I trust I have your attention?”

Ingrid whipped around. Ms. Groome was watching her through narrowed eyes, and her eyes were narrow to begin with.

“One hundred percent,” said Ingrid, in the faint hope of pacifying Ms. Groome with math talk.

“Then I’m sure you’re excited about MathFest.”

MathFest? What was Ms. Groome talking about? The word didn’t even make sense, one of those contradictions in terms.

“Very excited,” said Ingrid.

“Just in case Ingrid happened to miss any of this,” said Ms. Groome, “who wants to sum up MathFest?”

No one did.

“Bruce?” said Ms. Groome.

Brucie Berman, middle row, front seat, class clown. His leg was doing that twitchy thing.

“MathFest be my guest,” said Brucie.

“I beg your pardon?”

Brucie tried to look innocent, but he’d been born with a guilty face. “Three lucky kids from this class get to go to MathFest,” he said.

“And MathFest is?”

“This big fat fun math blowout they’re having tomorrow,” said Brucie.

“Not tomorrow,” said Ms. Groome. “Saturday morning, eight thirty, at the high school.”

“Even better,” said Brucie.

Ms. Groome pursed her lips, totally focused now on Brucie. There was lots to be said for having Brucie in class. Ingrid tuned out, just in time to catch that big black bird disappear around a bend in the river. No way this had anything to do with her, no way she’d be one of the chosen three. She shouldn’t even have been in this section, Algebra Two. There were four math classes in eighth grade—Algebra One for the geniuses, Algebra Two for good math students who didn’t rise to the genius level, Pre-Algebra, where Ingrid should have been and would have been happily, if her parents hadn’t crawled on their knees to Ms. Groome, and Math One, formerly remedial math, for the kids out on parole.

Math blowouts on Saturday morning. Who thinks these things up? Grown-ups, of course, the kind with a sense of humor like that warden in

Escape from Alcatraz.

Ingrid was half aware of Ms. Groome scrawling long chains of numbers on the blackboard, all dim and fuzzy. She wrote a note—

What’s the word for stuff like giant midget or

MathFest?

—balled it up, and tossed it discreetly over to Mia’s desk across the aisle. Mia was the smartest kid in the class, should have been in Algebra One, but she and her mom had moved from New York last year and the school had messed up.

Mia flattened out the note, read it, wrote an answer. The sun, one of those little fall suns, more silver than gold, shone on Mia’s hand—her fingers, skin, everything about her, so delicate. She rolled the note back up, flicked it underhanded across the aisle. Ingrid reached for it, but all at once, so sudden she wasn’t sure for a moment that it had really happened, another hand darted into the picture and snatched the note out of the air. Nothing delicate about this hand, skin scaly, knuckles all swollen.

“What could be so important?” said Ms. Groome, unfolding the note. “I’m dying to find out.” The sun glared off fingerprints on her glasses, hiding her eyes. She read the note, stuck it in her pocket, returned to the front of the class. Her mouth opened, just a thin sharklike slit. Some withering remark was on the way, but at that very moment, like a message from above, the bell rang.

Class over! Saved by the bell! Chairs started scraping all over the room as the kids got up. Hubbub,

and lots of it. Thanksgiving couldn’t come soon enough.

“Just a second,” said Ms. Groome, not so much raising her voice over the bedlam as cutting through it like an ice pick. Everyone froze. “We still haven’t chosen our MathFest team.”

Brucie raised his hand.

“Thank you, Bruce. Congratulations.”

“Oh, no,” said Brucie. “Wait. I was just going to say let’s do it tomorrow.”

Ms. Groome didn’t seem to hear. “Any volunteers for the other two spots?”

There were none.

“Then the pleasure will be mine,” said Ms. Groome. She smiled, if smiling meant the corners of the mouth twisting up and teeth making a brief appearance. “Mia. Ingrid. Everybody wish our team good luck.”

“Go team,” said everybody, in a great mood because it wasn’t them.

“But wait,” said Brucie.

“I could get sick,” Brucie said on the bus ride home.

Someone snickered.

“What if I forged a note?” Brucie said. “With

Adobe Photoshop I could make it look like a doctor’s—”

“Zip it, guy,” said the driver, Mr. Sidney, his

BATTLE OF THE CORAL SEA

cap slanted low over his eyes, like a ship captain in rough seas. Brucie zipped it; the other choice was walking the rest of the way, as Brucie had learned on the first day of school last year and then had to relearn again just last week.

Mr. Sidney stopped in front of Ingrid’s house.

“See you, petunia,” he said. Girls were petunia to Mr. Sidney, guys guy. Things must have been a lot different when he was growing up.

Ingrid stepped off the bus, started up the brick path to her house. Ninety-nine Maple Lane was the only place she’d ever lived. Not the biggest, newest, or fanciest house in the neighborhood, Riverbend, but there were lots of good things about it. Such as the breakfast nook in the kitchen with windows on three sides, where the family—Mom, Dad, Ingrid, and her brother, Ty, a freshman at Echo Falls High (home of the Red Raiders)—ate just about all their meals; and the living-room fireplace, the bricks set in zigzags that matched the brick patterns in the chimney and front walk, a nice touch in Ingrid’s opinion; and maybe most of all her bedroom at the

back, overlooking the town woods—the smallest room in the house, excluding bathrooms, and the most peaceful.

Ingrid went around to the side, unlocked the mudroom door. Nigel ambled out.

“Hey, boy,” said Ingrid, reaching down to pat him.

Nigel loved to be patted, maybe his second favorite thing, next to food. But now he changed course, making a kind of slow-motion swerve that took him just out of reach of her hand.

“Nigel?”

Nigel, crossing the lawn, swiveled his head around in her direction, walking one way, looking another. He had a jowly face and tweedy sort of coat, just like Nigel Bruce, who’d played Dr. Watson in the old black-and-white Sherlock Holmes movies; Ingrid, a lover of Sherlock Holmes, had them all on DVD. Her Nigel, like Dr. Watson, could be slow on the uptake. Unlike Dr. Watson, he wasn’t always reliable.

For example, the way he was now avoiding eye contact and had resumed his course, headed for the road. Nigel wasn’t allowed on the road. Ingrid, with a book in hand called

Training Even the Dumbest Dog

, had spent hours with Nigel, teaching him not to leave

the property, rewarding his eventual success with a pig-out of Hebrew Nationals, his hot dog of choice.

Nigel paused at the edge of the lawn, right forepaw raised in the attitude of one of those clever pointing dogs that understand commands in several languages. Was he remembering those hot dogs, even maybe just a little bit?

“Nigel?”

He stepped onto the street, a dainty little movement—like Zero Mostel in the

Producers

movie, one of Ingrid’s favorites—that still surprised her and always meant no good. The next moment he was picking up the pace, pushing himself into that waddling trot, his top speed.

“Nigel!”

Ingrid dropped her backpack, hurried after him. Nigel tried to go faster—she could tell from the furious way his scruffy tail was wagging, slowing him down if anything. He reached the other side of Maple Lane, sniffed at the Grunellos’ grass, and then made a beeline for the stone angel birdbath that stood by their front door.

“Don’t you dare,” said Ingrid, running across the lawn.

Too late. Nigel raised his leg against the birdbath.

Ingrid grabbed his collar and dragged him away, trailing a golden arc all the way back to the road. Nigel didn’t like the Grunellos, a quiet middle-aged couple who were kind to animals, never bothered anybody, and spent a lot of time away. Like now, please God. At the edge of the driveway he snatched up the Grunellos’ copy of

The Echo

.

“Put that down.”

But he clung to the rolled-up newspaper with all his might until they were back at the mudroom door. Then he dropped it in a casual sort of way and scrambled inside.

“Kiss those hot dogs good-bye,” Ingrid said. She could hear him panting in the kitchen as though he’d just performed some incredible feat.

Ingrid picked up

The Echo

, kind of drooly and tattered now. She’d have to make a trade, dropping their own copy back on the Grunellos’ lawn. But the delivery kid had missed them today.

Ingrid went inside, glancing at the front page. The big story was

SENIOR CENTER OPENS WITH A BANG

,

accompanied by a photo of some white-haired people laughing their heads off around a flowerpot. Below that was something about new rules from the Conservation Commission, pretty

much chewed through, and below that, under a headline that read

ECHO FALLS NEWCOMER

,

was a photo of a striking woman who looked to be a little younger than Mom. She actually resembled Mom—dark hair, big almond-shaped eyes—but although Mom was beautiful, you couldn’t call her striking. Ingrid gazed more closely, saw the prominent cheekbones, the fine shape of the lips, everything perfect, if a bit severe; maybe not like Mom after all.

Ms. Julia LeCaine, formerly of Manhattan, has moved to Echo Falls to take the position of vice president of operations for the Ferrand Group.

Hey. Dad worked for the Ferrand Group. And he was a vice president too.

Ms. LeCaine, a graduate of Princeton University with an MBA from the Wharton School of Business, founded an Internet company. A former outstanding soccer player, she was a Team USA alternate in 1992. Welcome to Echo Falls, Ms. LeCaine!

Ingrid went into the kitchen, took a Fresca from the fridge. Bliss, essence of. Whoever invented

Fresca was a genius. Could that be an actual job, inventing sodas? A whole new career possibility arose, handy backup in case her number-one choice, acting and directing on stage and screen, didn’t pan out.

Ingrid drained the can to the last drop, opened the trash cupboard under the sink.

“That’s funny,” she said.

At the top of the trash bag—which needed to be replaced, Ty’s job—lay

The Echo

, today’s

Echo

, still rolled up. How could that be? Mom and Dad were at work, wouldn’t be home for a couple hours at least, and Ty was at football practice, the only freshman on the varsity. Ingrid glanced over at Nigel, lying by the water bowl with one paw over his eyes in that way he had, as if warding off the light. Nigel—getting out of the locked house, retrieving the paper, depositing it in the trash, locking himself back in? Only in an upside-down universe.

Ingrid heard a footstep somewhere upstairs. Oh my God. She recalled a moment like this once before, when she’d helped Chief Strade solve the Cracked-Up Katie case. A creepy moment that led to all sorts of scary things. She stood motionless by the kitchen sink. Another footstep, right overhead. That would be Mom and Dad’s office, the extra

bedroom on the second floor. And was there something familiar about that footstep? Did footsteps have a sound unique to every person, like fingerprints but much harder to distinguish? Ingrid didn’t know; but she thought she recognized that footstep.

She went into the front hall, up the stairs, turned left toward the office. The door was half open. Ingrid peeked in.

Dad was at the desk, his back to her. The computer was on and he wore a suit—all Dad’s suits were really nice, with sleeve buttons that you could actually unbutton—but he wasn’t working. Instead he was slumped forward, his head on the desk.

“Dad? Are you all right?”

He sat up quickly and swiveled around. Ingrid caught a glimpse of his face as she rarely saw it—pale and anxious. Then came a smile and in a second he looked more like himself, the handsomest dad in Echo Falls.

“Hi, cutie,” he said. “What are you doing here?”

“Me?” said Ingrid. “I’m home from school.”

“Oh,” said Dad. “Right.”

“Everything okay, Dad?”

“Sure,” said Dad. He glanced at the computer, switched it off. “Just punched out a little early. All

work and no play—” He paused, waiting for her to finish.

“Makes Dad a dull boy,” Ingrid said.

He laughed.

The computer was blank now, but Ingrid had quick eyes and they’d grabbed that last fading screen: Jobs.com.