Batavia (22 page)

Authors: Peter Fitzsimons

5 June 1629, approaching Batavia’s Graveyard

Exactly as Jacobsz has predicted, no sooner have Pelsaert and his sailing party approached the shore of the larger island than a mob of men, women and children appear, all of them clearly desperate.

At this vision, Jan Evertsz is as abrupt as he is clear in his barked warning to Commandeur Pelsaert: ‘They will keep you and us there. We don’t wish to go nearer. If you have anything to say to them, you can call out.

We are not going to run any risk

for your sake.’ Just two days earlier, such an utterance to the high and mighty

Commandeur

would have been every bit as unthinkable as the refusal of sailors to follow orders – cause for their keel-hauling and torturous death. But things have changed.

Pelsaert is entirely powerless

to enforce his will on men who are not only facing the likelihood of their impending deaths but also, as rough sailors in a rough aquatic world, are more capable of forestalling that death than he is.

And yet, Pelsaert is still so outraged at the impertinence of the bosun that he decides to jump overboard and swim ashore towards the mass of people. He would have done so, too, had the bosun not suddenly gripped him tightly, even while telling his men to row away.

Finally, Pelsaert, though it goes against the grain of everything he has learned as a member of the VOC over the last 20 years, knows he has no choice but to accede to their demands and so ceases his struggle. The boat continues to pull away as the men haul rhythmically on the oars, the only sounds being their heavy breathing, the gurgle of the waves slapping against the sides of their boat and the splash of the oars as they simultaneously hit the water. Pelsaert gazes forlornly back at the mob on the shore, wondering

what can they be thinking?

On that shore, the gathered mob stare at the departing boat in stunned fury. The

Commandeur

is abandoning them!

The

Commandeur

. . . is . . . abandoning them!

He was right there, right about to land . . . and now he has simply left! It is incomprehensible. It is devastating. It is unforgivable. Women weep. Men stare with glassy eyes at his receding figure. The children – though they are growing up fast in these extreme circumstances – look closely at their frothing parents, trying to work out what has just happened to make them so desperately angry and so devastated, all in one.

Slowly, the group on the shore break up. They return to their primitive hovels, which they have fashioned out of whatever they were able to bring with them and whatever has washed up on the shore – mostly pieces of sail held up by broken spars and loose bits of timber. The one who is perhaps the angriest of them all is Ryckert Woutersz, the Mutineer who for so long slept with his sword beside him in his hammock, primed to move at Jacobsz’s command. He has been ready to back the skipper at the risk of his own life, ready to attack Pelsaert at a single nod of Jacobsz’s head, yet these two now look as if they are combining forces to abandon the likes of him on this godforsaken bit of coral at the edge of the world. It is treachery of the highest order!

CHAPTER FOUR

Batavia’s Graveyard

At present the pack of all disasters has moulded together and fallen on my neck . . .

Commandeur Francisco Pelsaert

6 June 1629, smaller island

It is time for Jacobsz and his men to do what most of them have wanted all along. They will head off this morning in search of water, first on the higher islands, then, failing that, on the coast of

het Zuidland

, which they know must be only a short way to their east.

Now, even though Pelsaert would be only a dead weight, he must decide whether or not to accompany them. On the one hand, he tells himself, as the VOC’s senior man in the midst of this disaster, it is his responsibility to make a full report of what has occurred to the VOC authorities in Batavia and to oversee the rescue. What, however, of the people he is leaving behind? Surely, if he stays, his authority will help to keep them calm? Surely he will be able to organise them to better assure their survival? Then again, he thinks back to the scene on the island the day before –

could

that rabble be organised? Yet, there is the agreement he has come to with Jacobsz and the crew that if they

do

find water on the other islands or the

vaste landt

, mainland, they will take it back to the survivors. If he is

not

with them, will they honour that?

His mind is at sea, his thoughts surging through him like the rolling surf through the battered bones of the

Batavia

– no sooner does the

Commandeur

land on one decision than it is flushed away by another quickly taking its place. One final factor that he cannot deny is that, in a choice between staying on islands with little food and water, with an abundance only of starving and thirsty people, and getting into a boat that at least has a chance of eventually turning towards the only outpost of civilisation in this part of the world, the latter option is always going to be the most attractive.

So, finally, he decides to go. The only problem is Jacobsz’s point-blank refusal to even countenance the possibility of his trying to take his heavy chest of valuables with them, on the grounds that it would cause the longboat to lie too low in the water, making the vessel unstable. As this is squarely within Jacobsz’s province of responsibility – and what he says is no more than logical, anyway –

Pelsaert must cede

.

So it is that not long after the sun comes up, Pelsaert along with Skipper Jacobsz, Opperstuurman Claas Gerritsz and everyone else who was on the tiny island proceed into the gloriously dark blue of the deepwater channel, passing right by Batavia’s Graveyard once more. This again arouses furious protest from the survivors there, who wave, shout and beckon them to come ashore.

‘Brood! Brood!’

they cry. Bread! Bread!

Alas, as Pelsaert learned the previous day, they could not approach the island even if they did have bread or water to spare. In a vain attempt to forestall any accusations of abandonment, the

Commandeur

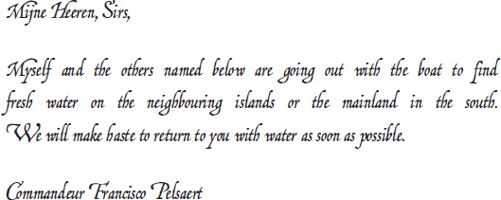

has left a message for those survivors back on Batavia’s Graveyard. Just up from where even a high tide might be expected to reach, there is, in clear view of the first person to land there – and it would be possible for a strong swimmer to get there from Batavia’s Graveyard – a bread barrel, albeit now empty, under which there is a note, penned by Pelsaert.

Click Here

As the people on Batavia’s Graveyard cry out once more when the longboat passes them by, Pelsaert averts his eyes. Not all of his men follow suit, however. One of them, Claas Jansz, the chief trumpeter, has just seen his wife, Tryntgien Fredericxs, on the shore, screaming for him, as she stands by her sister Zussie, who is doing the same. He and his wife became separated in the madness of the ferrying from the wreck, and they now lock eyes for the first time. But what can he do? Like many who make their living aboard ships, he cannot swim, and within a few seconds the longboat has pulled so far into the deepwater channel that it is simply out of the question for him to try jumping off the boat to get ashore. Besides which, he consoles himself, they will hopefully find plenty of water on the higher islands, and soon husband and wife will be reunited.

It is not just those on the larger island who are appalled to see the longboat disappear. There are those still out on the

Batavia

herself, watching them go and entirely unaware that Pelsaert has succeeded in insisting that, for the moment at least, the yawl should stay behind so it can help get more survivors off the ship once the weather has calmed. If it

ever

calms. For the huge waves continue to pound into the Abrolhos reef from the west, just as they have done for millennia.

For those souls still aboard the ship, it has been a tragic thing to see how quickly the once mighty vessel could be destroyed. Already, the

Batavia

is now a mere shell of her former self. The 70 survivors who remained aboard on the first afternoon of the wreck have now halved. One by one, the majority have tried their luck at drifting towards one of the two islands in the distance, clutching on to pieces of wood to help them stay afloat. Some drowned nearly immediately, the ocean swallowing them whole, squeezing the life out of their lungs and returning them to the surface, bloated and purple. Others appeared to have made it, though it is far from sure.

What is obvious is that, sooner or later, everyone will have to make the attempt, because each day sees a greater deterioration of the ship, and it will likely be only a few more days before the whole thing sinks beneath the waves. And yet, now, the one boat that can get nearly all of them off in the safest fashion is leaving them, heading north and already disappearing over the horizon! No one is more appalled than Jeronimus, watching closely from the poop deck, his half-lidded eyes taking it all in. What new game is this?

Quite what Jeronimus is going to do to survive, he isn’t yet sure, only that it will not involve him willingly throwing himself into that swirling and angry water. He will remain with what limited shelter the ship can provide right to the end.

Desperation is now Commandeur Pelsaert’s constant state. The only thing that changes, hour by hour, day by day, is that which he is desperate about. On this, the third day since hitting the reef, he is in the longboat with the 36 other crew members, all of them equally desperate to find water on one or both of the two larger, higher islands that lie west by nor’-west. From a distance, neither looks promising, as they are anything but green. But at least they are much higher above the sea than the two tiny islets they have come from, and there does seem to be

some

scraggly vegetation on them. Clearly, there is more chance of finding water there than anywhere else around them – where there is no chance at all.

There is, however, no deepwater channel beside these High Islands, and the boat is still nearly a mile off shore when its bottom lightly crunches upon rough rocks in the shallows. Reluctantly, they have to get out and wade forward, with great difficulty, half-lifting and half-dragging their boat to the shore.

At last ashore on the easternmost of the islands, their first impressions are dispiriting. With the apparent lack of a creek, or a spring, or pools of fresh water, they begin to dig, endeavouring to get down to water that they hope will be just a few feet or so below the surface. But their holes reveal only more sand beneath. The same happens when they venture a little further onto the island. The soil three feet down is marginally moister than the soil on the surface, but there is not the slightest indication that digging a lot deeper will yield a different result. True, at this point the obvious thing to do is for all of them to spread out around the two islands – it proves possible to wade between the two – but under the circumstances no one is keen to wander any distance from the longboat. That boat is the sole difference between them standing on a desert island and being stranded on a desert island, and everyone wants to keep it in sight at all times.

In the end, all they can find are some brackish pools of rainwater left in some of the small hollows on the cliffs of the larger island. Alas, sea-spray has made it so salty that it is only marginally closer to drinkable than ocean water. Sustaining themselves, thus, on only the supplies they have brought with them, they pass what proves to be a typical night in these parts – desperately uncomfortable.

7 June 1629, High Islands

The following morning is occupied with some more desultory searching for water, but with the same result. Things are looking grim . . .

Just before noon, Skipper Jacobsz engages in an extremely important task. As the skies have momentarily broken to reveal a half-hearted sun, it is time to use his astrolabe to calculate the position of his wrecked ship. It is something that must be accomplished quickly, as the sun comes and goes and there are a dozen other things he must attend to – most of which concern placating his sailors and ensuring that he remains in control – so he abandons his usual method. Instead of proceeding slowly and carefully, and checking all his calculations three times through, he does it just once.