Batavia (19 page)

Authors: Peter Fitzsimons

Worse still, by the first strains of light, the true grimness of their situation becomes clearer, as they see the jagged rocks and seething shallows all around. They haven’t hit at low tide; they have hit somewhere near high tide. It is impossible for anyone to stay upright for long on the deck, as the whole thing shifts and bumps alarmingly with every wave. Now, the ocean recedes around them even more, and they begin to see the cruel teeth of an entire reef emerging from the waves, extending out on both sides from the bow of the ship, as she starts to tilt over alarmingly to her starboard side. The breakers are hitting that reef for some two miles to port and one mile to starboard. The only gap in the reef appears to be about half a mile to port, where the force of a millennia of waves has carved a deepwater channel. If they were just a little more than a mile to their starboard, they would have missed the reef entirely, but that was not to be their fate.

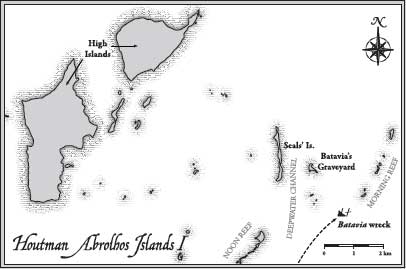

Jacobsz now has at least a rough idea of what has happened. Perhaps they are further to the east than he thought and they have run aground on the Houtman Abrolhos Islands, which the VOC has warned all skippers to stay clear of. Jacobsz believed they were still 600 miles to the west of them, but in fact it seems they are now . . . well . . . right on top of them. The skipper – perhaps because the

Batavia

has proven to be faster than most

retourschips

– has seriously miscalculated.

It means, at the very least, that Jacobsz’s captaincy career is finished there and then, but there remains a far more pressing issue for him to worry about. This is, simply, surviving long enough to have the luxury of being punished and losing his command.

And that is not going to be easy.

As the light of dawn continues to illuminate the seascape, they can see, even through the now pouring rain and still howling wind, that north-west beyond the reef are apparent the dim outlines of nearby low-lying islands, the nearest of which looks to be about a mile away. It is, to be sure, an enormous relief to know there are islands lying close and the ship has not simply hit a reef in the middle of the ocean, but the fear is that those islands might be covered when the high tide returns.

By now, a kedge has been rowed out and dropped astern, but, despite 30 men hauling with every ounce of their strength on the capstan, the ship fails to move a jot. They are well and truly caught, and as the tide continues to fall each movement of the sea causes the Indiaman’s hull to see-saw upon the reef, with the for’ard part landing with shocking blows. At the fulcrum of this macabre pivot is the mainmast, now turned blacksmith’s hammer. With each passing wave, which comes about every ten seconds, the mast rises to its full height, only to crash back down upon the cruel anvil of the reef. Each mast blow causes the whole ship to shudder in pain, right down to the base of her very keel.

It is now time to take the most extreme measure of all: the mainmast itself will have to be cut down. This will hopefully prevent it from pounding the ship to pieces and lighten the vessel to such an extent that, once the high tide returns in nine hours or so, the men might just possibly be able to refloat her. They would then get her to the shallows of one of the nearby islands and, after giving the carpenters the chance to repair enough of the damage, they could possibly still limp into Batavia.

Such are the severe ramifications of cutting down the mast, so heavy is the responsibility of doing it, that long Dutch tradition holds that

only the skipper can strike the first blow

. And so it is that, once the sailors have slashed all the rigging connected to it, Ariaen Jacobsz himself steps forward, spits on both of his hands, grips the axe with intent and, with one last look skywards at the mighty mast that was the pride of Amsterdam and the entire Dutch seafaring people, strikes a tremendous blow. The mast, of course, barely quivers, its many tons of timber only shivering a little.

The blow is more of a signal than anything else, and four sailors now step forward and begin hacking away with ever more frantic strikes of their own. In such circumstances, with the wind howling, the ship listing and the base of the mast continuing to pound down on the keel, it is never going to be easy to make the mast fall where they want it to – cleanly over the side and into the sea – so all they can really do is hope.

When at last, after 15 minutes of chopping, the mast finally gives way with a wrenching roar, such is the day, so malevolent are the maritime and nautical gods, that the mast with all its spars and sails and rigging falls exactly where they

don’t

want it to fall – straight down the length of the ship.

The massive mast destroys everything in its way and only narrowly misses a small knot of the ship’s company clinging on to the poop deck. Its impact on the deck pounds the ship harder than ever, and as the waves wash over the lower decks for the first time it is now obvious to all that the last glimmer of hope they have been holding on to – that the

Batavia

might still be able to get off the reef – is now dead.

‘The Lord our God has chastised us with many rods,’ laments Pelsaert.

‘Our back is as surely broken as the

Batavia

’s.’

With a series of frightening cracks, more of the spars on the mizzen mast now give up the unequal struggle and themselves break in sympathy, also roaring down to the deck below in a tangle of wood, canvas and rope.

Pelsaert and Jacobsz decide that the most urgent thing for now is to get the more manoeuvrable of the boats, the yawl, through the gap in the reef and into the channel to establish whether the two nearest islands can be used to safely deposit people and goods for the short term. Around and about them, as they make ready to launch once more, the seabirds continue to dive and whirl, caw-cawing with vague concern over these strange proceedings. At last, all is ready.

For such an important task as this, and at Pelsaert’s behest, Ariaen Jacobsz himself climbs down into the yawl, being held steady by several sailors already on board, and finally succeeds in getting away from the stricken

Batavia

, so they can reconnoitre.

Forlornly do the rest of the ship’s company watch them go, as they huddle on the deck with as many of their belongings as they can salvage pressed tightly to them. In the near distance, they watch the clearly visible sail of the yawl as it travels from a spot close to one of the small islands to another spot close to the other island – both of them are tiny puddles of land in an otherwise unbroken sea – and then at last comes back towards them

just before nine in the morning

.

With hope in their hearts again, they see Jacobsz return and clamber up the lee side of the

Batavia

.

‘Ja

, ’tis possible,’ he reports to Commandeur Pelsaert quietly, as the sailors – who in these extreme circumstances have stepped up in the hierarchy aboard the ship – huddle close to hear him. ‘There is nowt of shelter or fresh water on either isle, but both will be safe from the high tide. Neither is easy to land on, but ’tis possible.’

At least this is one small mercy, for there is now no denying it, the whole ship is beginning to break up. The timbers so carefully crafted and joined by the teams of master tradesmen back in the Amsterdam shipyard are coming apart plank by plank, as every heave lessens the

Batavia

’s resistance.

At ten o’clock, it finally happens. With one last agonised groan, and then a fearful

crack

, the for’ard part of the ship below the waterline on the port side bursts asunder as the ocean – denied access for eight months – has its final revenge on the

Batavia

and crashes through the splintered oak and into the hold. Some of those closest to the breach in the hull, including several carpenters and caulkers who are right at the spot trying to prevent from happening the very thing that has occurred, immediately drown, while others manage to scramble up to the higher decks just in time. Among those parts of the ship that will now forever be underwater is the

broot-kamer

,

bread-locker

.

As the hold fills with water, the ship shifts position, with the stern starting to sink ever lower and gravity beginning to grip everything not fixed in place and slide it downwards. This includes people.

Jacobsz, aghast, now gives orders that the priority of those still on the ship must be to salvage food and water first, and everything that is still dry must be brought up to the deck in great haste. He has high hopes of getting most of the ship’s supplies and people onto the sad, barren little strips of land substantially intact, but everything – heaven and earth and the very gods themselves – seems to be against them.

Any traces of cohesion and discipline among the crew have long since disappeared with the moon, replaced by something far closer to the heavy storm clouds that have now gathered overhead. It was one thing to take strict orders from someone in authority when all was calm, when the presence of the Company was felt in the air they breathed and the penalty could be as high as death for disobedience. But it is quite another when all seems lost, and when this same authority has guided you onto this godforsaken reef. Suddenly, the Company is not there any more for the common sailors and soldiers, and those who do obey orders are doing so more because they understand it is their best hope of redemption than because of any lingering loyalty.

On the deck, some people have become so desperate to get off the ship that they hurl themselves into the surf in the hope of swimming to the island. No fewer than a dozen of them are grasped by the capricious claw of this raging animal of an ocean. They are cast up, then flung down upon the reef, and thereafter drown.

In this weather and these waters, no one can truly hope to swim to the nearby islands, and nor does it seem possible that anyone can stay for long on the

Batavia

, as the ocean continues to pound her and the wind to howl.

They are where they are, and there they will stay until they are either rescued or able to launch the other boats. Obvious to nearly all, the 32-foot yawl and the 40-foot longboat – both of which have oars and sails and can carry, respectively, ten people and 35 people comfortably – are all that stand between the ship’s company and certain death.

As tiny as the closest island is – just three times the length of the

Batavia

and not a lot wider, with no vegetation to speak of or even soft sand to rest on – it is at least solid land, above water, which is a very good start in the circumstances. With this information, the sailors and some of the soldiers set to with a will, making ready to begin ferrying people to dry land. In the time since the mast has fallen, the situation on board has continued to deteriorate, and time is now of the essence.

At this point, had they been left entirely to their own devices, both Jacobsz and Pelsaert may well have tried to start ferrying their precious cargo to the island, leaving the people till last. By this time, however, it is obvious that if they even attempt such a thing while the panicking, howling people on the deck clamber to board the boats even before they are in position, there will be an open revolt.

Thus, despite the appalling conditions, they begin to ferry people to relative safety, while several of the ship’s senior officers start to laboriously bring the precious cargo of money chests and other valuables to the main deck and secure it.

Some of the sailors and soldiers help in this process. Others are either too panicky or now believe it doesn’t matter what they do, for all is lost – and so refuse to cooperate. Still, though, there are just enough sailors and soldiers remaining at their posts and staying relatively calm to keep up the difficult operation of getting passengers from the deck of the

Batavia

into the yawl and longboat whenever they come alongside.

Notable among these are two Dutch soldiers, Wiebbe Hayes and Wouter Loos. Pelsaert has already noticed Hayes, in particular, quite a few times on the trip, and he has not noticed many other soldiers.

There is a way this man carries himself

that marks him as a cut above, even though he remains humble, something about his quiet, competent manner that is appealing and lends confidence to those around him . . . and never more so than on this occasion.

Every time the boats pull alongside after transporting more people, Hayes is there on the deck of the

Batavia

, helping passengers down, passing supplies, offering soothing words and doing whatever needs to be done to accomplish the hazardous task as safely as possible.

And, so, the day wears on. By the time the afternoon deepens and the light begins to fade, Jacobsz and his men have managed to ferry 180 people to the closest and tiniest island, along with ten casks of bread and several barrels of fresh water. In the madness of it all, husbands have been separated from wives, and children from parents, but the main thing is that over half of the ship’s company has been transferred, along with Pelsaert’s exceedingly heavy casket of jewels and the cameo –

together worth well over 50,000 guilders

.