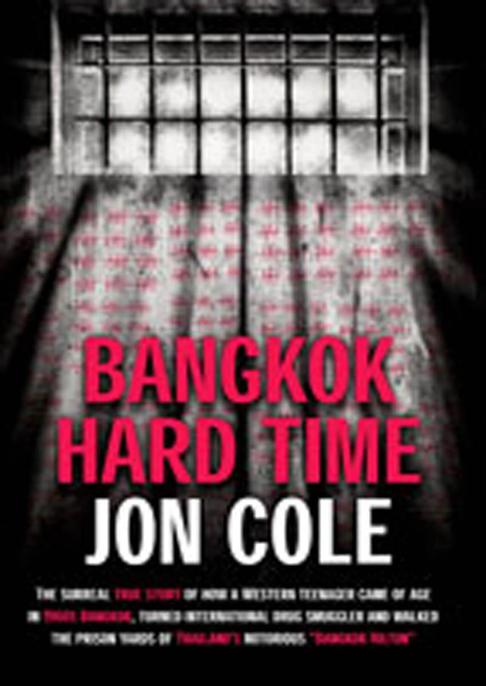

Bangkok Hard Time

Authors: Jon Cole

BANGKOK HARD TIME

J

ON

C

OLE

Contents

I Get Thai With A Little Help From My Friends

Into “The Crocodile” Via “The Lizard”

For

Carolyn Saluga

my International School Bangkok

English teacher, who would quote Socrates:

“The unexamined life is not worth living”

Into The Kingdom

As the plane dropped beneath the clouds on final approach, an enthralling vista appeared. Below was a maze of tree-lined canals lacing endless farms and rice paddies as far as the eye could see. All were in various mottled shades of reddish ochre and emerald green, surrounding a large sprawling city built around the wide brown river that undulated through it. So this was Bangkok.

All I knew of Thailand back then was that it used to be called Siam and that we were going there because it was close to Vietnam. All I knew of Vietnam was what I had seen on the daily TV news reports covering the latest war updates. The idea of living in a Third World country under the thatched roof of a bamboo hut was not my idea of “cool”. I was a silly sixteen-year-old punk who had just gotten a driver’s license. There would be no driving in Thailand, my father had said, though he assured us that we would not be living in a hut. That was damn small consolation. I was going to miss out on car-dating, drive-in movies, cruising with rock tunes blaring and hanging out at the Dairy Queen, amongst other juvenile joys. The mobile American teenage dream life quickly faded as a possibility from my perturbed adolescent mind.

The last days of 1966 found our family aboard this Saturn Airlines Boeing 707, leased by the US military, en route from Travis Air Force Base, California to Bangkok, Thailand. My father, an Army Green Beret colonel one year back from his first tour in Vietnam, had told us in his seemingly grandiose manner that we would be in Thailand as guests of The King.

My dad had been assigned to be an advisor to The Queen’s Cobra regiment of the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Force destined for Vietnam a year later. On board, in addition to my mother JoAnn, younger brother Steve, sister Carol and five-year-old brother David, were 150 or so US Army enlisted personnel … all of us without any clear idea of what to expect.

Upon stepping through the doorway of the plane, I was hit with an almost visible wall of warm heavy humid air that, bewilderingly, smelled both sweet and sour. Each arrival’s reaction to the new environment was different. Some covered their noses, some sniffed curiously and some cautiously. To me, it was enticing. Again on the many trips over the decades to follow, that first breath of warm moist Thai air upon disembarking was an experience, which I looked forward to with both a delicious anticipation and an undefined apprehension.

A short shuttle bus trip from the plane took us to the airport terminal where all passengers were gathered into a large hall. While we waited for our luggage, I overheard a grizzled US Army first sergeant standing on a chair to deliver an obligatory “Welcome to Thailand” orientation spiel to the company of GIs under his charge that had come off our flight.

The first sergeant was a tall, gangly black man who spoke with such a strikingly strong Southern accent that it sounded almost like a speech impediment. Additionally, he was speaking so slowly that one might even suspect that he may have been a little intellectually challenged. Those vocal qualities, working in combination with his monotone delivery, flipped the switch in your brain that tells your ears to listen to something else, which is what many in the hall were doing. Most of the GIs were engaged in excitedly hurried and hushed conversations concerning bars, bargirls and other closely related activities.

At first, I was straining to listen to the first sergeant’s words, but soon I found myself feeling compelled to hear what he had to say, almost as if you were listening to an oracle or a provender of what the future may hold. At times, I almost imagine that I can still remember what the first sergeant had said that day, word for word.

“You are now a guest in another people’s country and are expected to conduct yourselves accordingly,” the first sergeant announced in his painfully slow plain-spoken manner. “You are to respect and observe the laws and customs of the host population regardless of what you think of them.

“For example, you will not point with your foot. You will not touch a Thai person on their head. You will never touch a Thai child, though you may allow them to express their curiosity about you physically. For example, by pulling the hair on your arms or trying to examine your clothing. Because I am black, the children will sometimes want to touch my skin to see if it feels different.”

Then he advised, “If for any reason you have a problem with an adult Thai person, wait to see if another adult Thai will intercede for you, which, you will find, usually happens. When in doubt, smile and keep your hands to yourself.”

“Thailand has a king,” he continued to drone on in a monotone which sounded almost mantra-like. “Never demonstrate any disrespect to The King or images of The King. For example, you must stand when the Royal Anthem is played in a movie theater. Disrespect The King and you disrespect almost all Thai people. This is not The King’s law, it is the Thai peoples’ law.”

There was then a long pause and many thought the lecture was over until he continued with a final admonition.

“Obey the laws here and comply with Thai authorities or you may find yourself in a Bangkok jail, where there is very little we can do for you. The Thai people have the power here. Remember that you are here as a guest. Welcome to Thailand. You are dismissed.”

The GIs went in one direction. My siblings and I headed off in another direction. This was almost a metaphor for what was to follow. Over the next few years, my paths and theirs would cross but our experiences, perception and appreciation of Thailand would often differ greatly.

In preparation for his assignment, my father had been stationed at the Defense Language Institute of the Presidio in Monterey, California to learn the Thai language. Our father would come home and speak Thai to us; as a mini-immersion exercise, I suppose. We could not help but retain some of what we had heard. The language intrigued me and the ability to speak a few words of Thai upon arrival in the country certainly eased the transition

Also stationed at the Presidio at that time was Colonel Kelly. His lovely daughter Jean Marie was my friend, one-time beach outing companion and the young lady whom I have always considered as my first date. We had walked down the hill from the Presidio to the beach and waded in the cold water of a December Monterey Bay until chilled. Then with teeth chattering, we went to the fisherman’s wharf and rented a crab net, catching only a mutilated starfish. At dusk we walked back up the hill to The Presidio. After climbing the lower branches of the huge live oak tree between the giant old cannon and the NCO club, we had shamelessly held hands for almost a minute.

Now three years later in Bangkok, it was Colonel Kelly and family who greeted us at the airport following the first sergeant’s orientation speech. Colonel Kelly was initially my father’s superior and army-assigned sponsor or host. The Kelly family invited us over for dinner a few times. The lovely, gracious and popular bookworm Jean Marie took me around Bangkok, introducing me to some of the other kids at the American Teen Club, thus smoothing my introduction into the high school social scene there.

After weeks at a small hotel across the street from the US military-based Capitol Hotel, we moved to the house which would be our residence for the next few years. The structure was a huge, Thai-style home. Eight-foot-high walls surrounded the large manicured compound topped with broken glass bottles set into the concrete seams of the terracotta tiles. A cook, a maid, a gardener, a night watchman and a shy, pretty little wash girl had a separate house inside the compound. It was indeed a far cry from the bamboo hut that I had imagined. My premonition of living in a thatched roof bamboo hut would, however pathetically, become a reality almost two decades later.

On school days, a bus picked up my siblings and me at our compound and then duly delivered its cargo to the International School Bangkok (ISB) on Soi 15 off Sukumvit Road. (

Soi

is the Thai word for a small lane off a main road.) The ISB, a large school comprising elementary through high school classes, was indeed international in student body with all instruction conducted in English. Most of the students were American children of either US military, US State Department or related US assistance groups who were familiar with the experience of re-acclimating to a new place every year or two. It was no surprise to meet kids that you had known in other locations around the world where our dads had been stationed.

The sky over Bangkok was always filled with the contrails of B-52s either heading to or returning from bombing runs over Laos and Vietnam. None of the kids attached any significance to it other than that it was simply something some of our fathers were doing and an explanation as to why we were even there in Southeast Asia.

The sprawling campus of the school was within a guarded, limited-access walled compound. Once inside, it seemed almost like any other Stateside school. Even the cafeteria menu closely resembled American school fare. I quickly grew to hate sloppy joes. The cafeteria or snack shop did not serve any Thai food, which I found to be strange. The whole atmosphere seemed set up to insulate us from the real Bangkok just outside the walls. In spite of this insulation, culture shock was rampant among some kids, especially those who had never lived in a foreign country before.

With the exception of the small number whose families had lived in Thailand for an extended period, very few of the ISB students spoke more than a handful of words in Thai. Fewer still had any Thai friends, despite the fact that we were surrounded by millions of Thai people. It became a source of consternation for me when any of my classmates would adopt an elitist stance and treat the indigenous population with an air of superiority. It obviously was not a racial bias since many of the ISB kids were themselves of mixed races. Unlike the lower enlisted personnel (GIs) who typically had chosen to self-segregate themselves racially, the children of the American military higher rank had long ago left all that bullshit behind.

Unfortunately, the general thinking there was that the reason for the American presence in Thailand was to protect the weak little nation of Thailand from the Vietnamese. The arrogance behind that attitude made the typical “ugly American” appellation a charge that aptly applied in this case. Most kids were disdainful of the Thais as if it was their fault we were living out our prime teen years in this backward Third World country.

Some of the GI’s were even worse. Many would refer to the indigenous population as “dinks” or “slopes” and clearly treat them as their inferiors. Obviously, they had not yet taken that “Welcome to Thailand” orientation speech to heart. Our Thai hosts generally attributed these social

faux pas

to our own individual character flaws.

At first, admittedly, I also fell into that trap of ethnocentric thinking which kept me aloof out of ignorance and arrogance. One incident that stands out for me in this regard: a short couple of months after first arriving in Thailand, I spoke to a cab driver who was carrying me to some now forgotten location.

As I recall, it was an instance where I was supposed to arrive at a pre-arranged time and place to meet some other ISB friends. The traffic was heavy and my driver seemed in no particular hurry. When I berated and cursed him in English, he slowed and pulled over to the side of the road. It became quite evident that he understood what had been said because when he replied to me his remarks were spoken in the most sublime English with no detectable accent. Using some words of my own language I did not even really know the meaning of, he softly put me in my place by saying “Young man, you look like a handsome, intelligent student, but when you speak to me in this demeaning and deprecating manner, you appear unpleasant and ignorant.”

I immediately and shamefully realized that he was right. When I sought to apologize, he would not hear of it and told me to get out of his cab.

“I will take you this far for free,” he said. “But when you board the next taxi, you should present yourself as a young gentleman instead of as a rude boy,” was his parting advice. It was a changed young man that stepped into the next cab that stopped for me.

For the most part, we were ignorant of the fact that we were living amongst a civilization that was over seven hundred years older than our own. Unlike the neighboring countries of Burma, Laos and Cambodia, the nation of Thailand during the last millennium had never been colonized by a foreign power.

The same Thai governmental system that had seen the country transformed from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy in 1932 was still in power when WWII came along. Thailand had aligned itself with the Japanese by collaborating in order to preserve the country’s independence and even issued a declaration of war against the United States. However, the Thai people eventually turned against their own government and its Nipponese protectors.

During those years of collaboration, the Japanese built a huge facility, Klong Prem Central Prison, to hold the overflow of various malcontents, assorted criminals, members of the opposition and some higher value prisoners of war. The prison, which would soon become notoriously known as “the Bangkok Hilton”, was a place which I myself would also someday call home.

Meanwhile, among the American children there was a lot of moaning, whining and commiserating about the cool life they thought we were all surely missing back in the States. Many flitted from one air-conditioned, Westernized venue to another. These included the US Officers Club, the American Teen Club, the Polo Club or any of the many American-style restaurants catering to

farangs

(Thai loan word for foreigners) and their desire for things comfortably familiar in a neo-colonial manner. Indulging in the familiar was OK for a while. But soon I found that there were so many more exciting activities to pursue outside of the comfort zone we had burrowed ourselves into.

Before long, the bad boys of the school took me into their ranks. As young punks with tough-guy attitudes and a generally misplaced notion that we were

too

cool, the underbelly of Bangkok looked ripe like very inviting territory for our testosterone-laden egos.