At All Costs (19 page)

This final step nosed the Stuka over into its dive toward the

Santa Elisa.

“In order to judge the steepness of the dive, there were lines marked on the starboard side of the canopy, which when aligned with the horizon indicated a dive angle of up to ninety degrees,” said Captain Brown of the RAF. “Now, a dive angle of ninety degrees is a pretty palpitating experience, for it always feels as if the aircraft is over vertical and is bunting. But as the speed builds up, the nose of the Ju 87 is used as the aiming mark. All this while

terra firma

is rushing closer, with apparently suicidal rapidity.”

If the German had any such thoughts of death, they were misplaced. His threat was not terra firma, nor the sea, nor the cold steel deck of a ship. It was an angry Norwegian gunman who was taking the war personally. If the fight between freighter and dive-bomber got down to

mano a mano,

this time the pilot didn’t have a prayer.

Larsen stared the Stuka down, through the concentric circles of his scope, as the 500-kilo bomb on the plane’s belly raced toward his bull’s-eye. Tracer fire streamed from the other ships and slipped beyond the Stuka, disappearing in diminishing gold streaks into the darkening sky, like hundreds of shooting stars traveling in reverse. The young pilot watched them whizzing past his wings, his heart beating like the thump of a Bofors as he desperately waited for the red light on the altimeter to flash so he could whack the knob that would release his bombs and pull his plane out of the dive that seemed as though it would never end.

Larsen held his fire until he was sure he couldn’t miss. He never went off half cocked about anything. The Stuka kept diving. Larsen kept waiting.

When it was time to shoot, he was calm and cold. He squeezed the trigger in his right hand.

This one’s for Minda.

He watched his tracers silently speed between the circles in his sight. It was nearly night, and the small dark Stuka in the scope looked more like a bat than a bomber. As the tracers met their target at top dead center of the concentric circles, the Stuka flashed like a bulb in an old camera. Chunks of German steel scattered into the evening sky, and red flames streamed like blood over the fuselage, charring the swastika on the Stuka’s tail.

“Third Mate Fred Larsen, stationed at a 20mm Oerlikon gun amidships, shot down a Stuka at about 1,000 yards range,” reported Ensign Suppiger. “It crashed into the sea on our starboard beam, about a ship’s length off.”

The dive that the pilot thought would never end had ended, about five hundred feet short of his target.

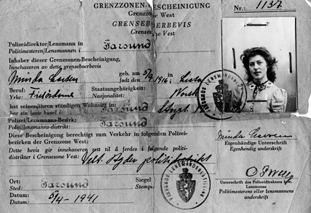

COLLECTION OF MRS. M. LARSEN

When Fred Larsen was three years old, he lost his father, mother, a sister, grandfather, and grandmother to the global flu pandemic. He was sent to Norway to be raised by an uncle, who died when Larsen was ten. He went to sea at seventeen, and never looked back.

COLLECTION OF MRS. M. DALES

Lonnie Dales, an all-American boy from rural Georgia, was born brave. He boarded the SS

Santa Elisa

at eighteen, fresh out of the new U.S. Merchant Marine Cadet Corps, and was assigned to an Oerlikon rapid-fire cannon on the bridge, under the mentoring eye of Third Officer Fred Larsen.

IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM, LONDON - HU 66906

Larsen attended mariners’ college in Norway, where he married Minda, the farm girl who stole his heart. He returned to sea in the summer of 1939. On April 9, 1940, their first wedding anniversary, Germany invaded and occupied Norway. Nazis came by sea, their ships looming off Norway’s rugged coast. Minda and Jan—the infant son Fred had never seen—were trapped.

COLLECTION OF MRS. M. LARSEN

The Gestapo issued Minda an ID. German soldiers filled the streets outside her small apartment. They staggered back to their quarters late at night, loud and drunk, just outside her bedroom window. She held her son to her breast, and whispered in his ear that his father would bring them to America.

BILL KOOIMAN COLLECTION

The attack on Pearl Harbor put the U.S. at war with Germany, and U-boats soon began sinking merchant ships along the Atlantic Coast. The

Santa Elisa

was the target of

U-123

. In a mystery at sea, the

Santa Elisa’s

hull was ripped open, and her cargo of fuel ignited. Larsen and the chief mate led the firefight for nearly five hours. When lives were at stake, Larsen was the first to arrive, and the last to leave.

IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM, LONDON - A8701

More bombs fell on Malta in April and May 1942 than on London during the entire Battle of Britain. Axis planes came in hordes from nearby Sicily. Limestone rubble filled the streets, and Maltese lived in caves as enemy submarines and bombers kept Allied merchant ships from bringing in supplies. With no natural sources for food or water on the arid island, some 270,000 people starved.

IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM, LONDON - A16150

For the first two weeks after the siege on Malta began, the island’s entire air force consisted of these three overachieving Gloster Gladiator biplanes, called Faith, Hope, and Charity.

IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM, LONDON - A19000

Night bombing raids were frequent, and the Royal Malta Artillery painted the sky with streaks of white light from antiaircraft fire. The guns could be controlled by one man in a bunker, like a wizard showering the sky with shrapnel and big bangs.