At All Costs

CONTENTS •••

CHAPTER 1

Malta, Summer of 1942

CHAPTER 8

From Nelson to Cunningham

CHAPTER 9

Debut of the Luftwaffe

CHAPTER 14

SS

Santa Elisa,

June 23

CHAPTER 19

Admiral Neville Syfret

CHAPTER 20

Lieutenant Commander Roger Hill

CHAPTER 24

Dive-Bombers at Dusk

CHAPTER 25

Bad Day for Secret Weapons

CHAPTER 26

Ithuriel

and

Indomitable

CHAPTER 28

Captain Ferrini’s Amazing Hat Trick

CHAPTER 29

This One’s for Minda

CHAPTER 30

Screams on the Water

CHAPTER 32

Retreat of the

Commodore

CHAPTER 34

Night of the E-Boats

CHAPTER 35

Hell in the Aftermath

CHAPTER 38

Swerving Toward Malta

CHAPTER 40

Lame Duck off Linosa

CHAPTER 45

The Teetering Tirade

CHAPTER 46

Nine Down, Four Home, One to Go

CHAPTER 48

Moscow Saturday Night

For Grandma Moses, who lived to see it

PART I •••

FATE IN THE CONVERGENCE

CHAPTER 1 •••

MALTA, SUMMER OF 1942

I

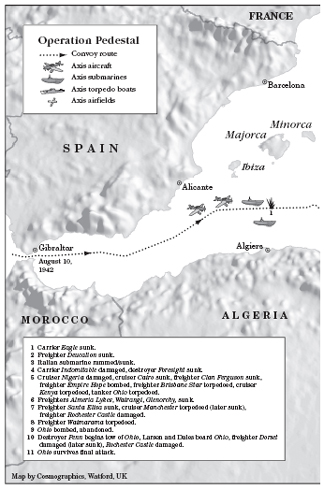

n the summer of 1942, scores of thousands of men, women, and children were starving and living in caves and tunnels on Malta, a block of limestone the size of Cape Cod rising out of the Mediterranean like a little white pebble kicked by the toe of the boot of Italy.

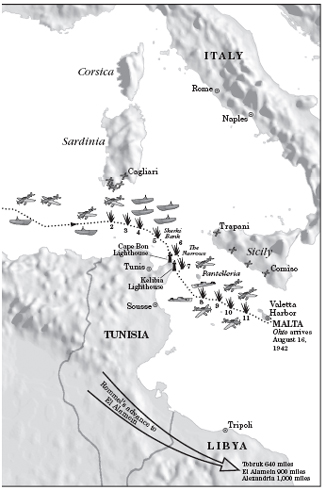

The island had been under siege for two years. Malta was the most heavily bombed place on Earth, with more bombs falling in April and May than during the entire summer and fall of the Battle of Britain. German and Italian planes flew from airfields on Sicily, just sixty miles north of Malta. If Italy was the boot kicking Malta, Sicily hung over the island like the massive other shoe, ready to drop.

“Malta is not only as bright a gem as shines in the King’s Crown, but its effective action against the enemy communications with Libya and Egypt is essential to the whole strategic position in the Middle East,” Prime Minister Winston Churchill told the House of Commons. It was an understatement for him. Sometimes stubborn but never alone on the issue, Churchill believed that Malta must survive for the war to be won. He might have echoed Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, who wrote, “Malta, my dear sir, is in my thoughts sleeping and waking,” to the Russian prime minister in 1799.

“It was evident that Malta, laying as it does in the very center of the Mediterranean, and flanking the Italian lifeline between Italy and North Africa, was not only of the greatest importance, but was, in fact, the vital key point which must be held at all costs,” said Governor-General William Dobbie. “Its loss would obviously open the door to disasters of the first magnitude, the outcome of which was not good to contemplate.”

“I cannot believe that Malta was more desirable a prize [for the Axis] than Moscow, but there was really no comparison,” said Air Marshal Hugh Lloyd, the Royal Air Force commander on Malta in 1942. “Malta stood athwart the path to Cairo and our oil in Iraq, and had to be eliminated first of all.”

It was all about oil, again. Churchill called Malta the “windlass of the tourniquet” on the supply lines of General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps, and Rommel was after the Mideast oil, which fueled the British war effort. Axis convoys from Italy to North Africa kept Rommel in supplies, but submarines and bombers from Malta destroyed much of that shipping; bombers also made runs over North Africa, striking truck convoys. If Malta were to fall, and the Luftwaffe and Italian Navy were to move in where the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy were desperately hanging on, Churchill believed it would be impossible for the British Army to keep Rommel from marching across North Africa and taking Egypt. After that, the Mideast oil fields would be lost. Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Persia (Iran) would be Hitler’s.

This was Hitler’s “Great Plan,” in which his army would conquer Russia, come down through the Caucasus, and meet the Afrika Korps to complete a Nazi wall encircling Europe, looping clockwise from Scandinavia to Spain, confining and enslaving Europe.

“With Malta in our hands, the British would have had little chance of exercising any further control over convoy traffic in the Central Mediterranean,” said Rommel, who pushed Hitler for an invasion of the island, to get it out of his way.

“Malta was really the linchpin of the campaign in the Mediterranean,” said Admiral Andrew Cunningham, Commander in Chief of the British naval forces in the Mediterranean and Britain’s greatest admiral since Nelson. “The island served as the principal operational base for the surface ships, submarines and aircraft working against the Axis supply line to North Africa. The Navy had always regarded the island as the keystone of victory in the Mediterranean, and considered it should be held at all costs.”

Cunningham’s German counterpart, Admiral Eberhard Weichold, wrote in a report to Hitler, “It cannot be emphasized sufficiently often, that a Malta capable of fighting is essential to the possibility of effective action against the African supply route for the Panzer army, and, moreover, a cornerstone in the whole defense of Egypt and the English position in the Mediterranean and the Middle East. I see only one possibility, and that is through a strategical offensive: The British Air Force in the Central Mediterranean, that is Malta, must be obliterated.”

“There was no lasting solution for the enemy short of the conquest of Malta,” said Churchill.

The stomachs of the Maltese might have been empty, but their hearts were pure and their faith indomitable, and they didn’t die easily. They had been digging into the limestone and living in caves forever, and their tolerance was nearly as strong as their belief in the power of the Virgin Mary. There are limestone temples on Malta five thousand years old, the most ancient man-made structures in Europe, older than the Egyptian Pyramids. They were built like bomb shelters ahead of their time, with altars believed to be for worship.

Seventy-eight churches, thirteen hospitals, and twenty-one schools had been bombed in the two years since the beginning of the siege. Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica bombers had made thousands of runs over Malta, destroying an uncountable number of other buildings and killing more than five hundred people in April alone. The magnificent Opera House in Valletta had been reduced to rubble, and it remains a monument in ruin to this day. A 500-pound bomb fell through the Mosta Dome in the ancient walled city of Mdina, skidded across the floor of the church as three hundred people were praying, and came to a stop without exploding. It was clearly a miracle, they all said.

The bombers turned the towns to mountains of limestone rubble, and then turned the big blocks of rubble into smaller blocks: rubble to rubble, dust to dust. Sometimes a house that had been bombed to rubble became a family’s new home, its limestone blocks rearranged into a limestone cave. Or sometimes a family moved out of a perfectly good home and into the security of a cave, which they often dug themselves. Some of the caves were no more than big dents in a cliff, which the Maltese called “caterpillar caves.” They also called them “ready-made graves.”

The soft limestone hardened when exposed to the salt air. Irish coal miners were brought in to help dig the caves, because they had the skills, and because the Maltese men worked all day in the dockyards or manned the antiaircraft guns around the harbor and at the edges of the island. The possibilities for tunnels were endless. Passageways led to one- and two-room homes and communal areas. People in the cities around the harbor lived their hungry lives underground, sharing all the sights, sounds, and smells, all the fighting and loving and living and dying and sometimes birthing, and always the praying, with the Virgin Mary hovering in every cave.

Sand flies flew out of the cracks in the limestone, carrying their fever. Cockroaches, bedbugs, and lice ruled. The “Malta Dog,” a virulent form of dysentery, barked in the corners. The hunger never went away.

Lacking a river, forests, and rich soil, Malta could provide little of its own food and none of its fuel, so its survival depended upon cargo ships. Supplies coming from Gibraltar, 999 miles to the west, and Alexandria, 866 miles east, had been cut off by Axis air forces and navies. Some foodstuffs trickled in over the “Magic Carpet,” a slim trail of fast minesweepers and minelaying submarines from Alexandria, but not nearly enough to sustain the island’s 270,000 people.

The Maltese lived mostly on rationed bread, olive oil, and tomato paste, drank homemade wine they called “screech,” and smoked bamboo for want of tobacco. The macaroni factory operated only when there was flour. Citrus, fig, date, and almond trees grew wild on the island, but they were perpetually picked clean. Adult males received a weekly ration of six ounces of rice, six ounces of preserved meat, six ounces of preserved fish, and five ounces of cheese. Women and children received less. Victory kitchens served one thin meal a day, maybe a skinny sausage and some peas; the goats had all been eaten, and the spring potato crop had failed. Chickens, eggs, milk, and fruit were sold on the black market, but the price was beyond reach to all but a few. Beasts of burden killed by bombs were bled and butchered if it could be done before they began to rot.

By the summer of 1942, any freighter sent to Malta was virtually on a suicide run. The sea was prowled by vicious “wolfpacks” of Axis submarines. The sky was blotched by aircraft from Sicily, Sardinia, and Libya, the Italian colony stretching much of the length of the North African coast. Fast and deadly torpedo boats, which the Italians called E-boats, owned the night.

The 10th Submarine Flotilla on Malta had done its best to protect the cargo ships coming in, but a handful of subs running on empty wasn’t enough for the job. The flotilla’s home was on the fifty-acre Manoel Island in Marsamxett Harbor, where its personnel hunkered down against the bombing in the sheltered limestone buildings of a former

lazzaretto,

which had quarantined victims of the plague in the sixteenth century, and more recently been a leper hospital. But the Luftwaffe blitz in April had chased the “Fighting Tenth” to Alexandria, with its five remaining subs. There wasn’t enough diesel fuel left on Malta for them, anyhow.

That left the defense of the island up to the Royal Malta Artillery and the struggling Royal Air Force, which flew from three primitive bases on the island. But diesel fuel was needed by the generators making electricity for the RMA antiaircraft batteries, which were connected by wires strung across the island and could be controlled by one man in a bunker, like a wizard showering the sky with shrapnel and big bangs. Generators also powered the searchlights and radar stations that spotted enemy aircraft.

Meanwhile, the RAF bombers and fighters were running on fumes. The RAF was so low on aviation fuel that planes were towed by a tractor to the runway, to save the pints used by taxiing. When the last tractor was blown up by bombs, the ground crews began pushing the planes.

In addition to the diesel needed by the submarine fleet, fuel oil was needed by the Royal Navy warships, minesweepers, and tugboats, a few of which were based on Malta, with others coming and going. The movement of the fleet into the central Mediterranean from Gibraltar or Alexandria required the refueling in Malta of destroyers and sometimes a battleship. But by the summer of 1942, the fuel was no longer there for them.

Kerosene was also needed on the island, for heat, light, and cooking. It was rationed and sold from carts guarded by policemen, to prevent black market sales.

The diesel, fuel oil, and kerosene were often blended, leaving little distinction. The submarines, warships, freighters, and antiaircraft guns used any and all of it for fuel. Malta’s survival was down to one thing: a tanker carrying oil must get in.

It had been nine months since a convoy with freighters had made it to Valletta, Malta’s harbor city. Eight solo cargo ships had trickled through in that time, but that scarcely postponed the reckoning. Malta’s days were numbered, literally; a secret countdown was on, to September 7. Governor Dobbie had recently taken an inventory of the food and fuel, and had informed Prime Minister Churchill that if a convoy didn’t get through by then, Malta would be forced to capitulate to the Axis.