As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth (2 page)

Read As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth Online

Authors: Lynne Rae Perkins

T

here was one bar of reception.

Ry called his own house first, where his grandfather was staying, along with the dogs. It was nice to hear another voice, even if it was his own, on the answering machine. He listened, then left a message that he hoped sounded urgent (“Something unexpected has come up and I need to talk to you to figure out what to do about it”), without sounding too alarming (“Don’t worry, I’m okay”). His grandfather was an old guy. He didn’t want to make him panic.

Wondering if his grandfather would remember to check the answering machine, he called his parents’ cell phone. Another thing he didn’t want to do was to wreck their Caribbean Sailing Idyll, but this seemed like a circumstance they would want to know about.

“Come on, you guys, answer your phone,” he said as it rang and rang.

What was left of the battery was fading from searching so hard for the faint signal, so he turned the phone off. It sang out its good-bye and turned out the lights.

“Okay,” he said aloud.

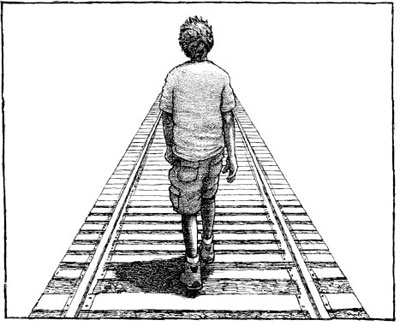

He looked again at the town. He would walk. He would walk along the train tracks. The tracks probably went through the town, or near it. The river was nearby, at least here, so he could take drinks. There would be people in the town, and he would figure out what to do next.

Unless it’s a ghost town, he thought, which almost made him laugh. But not quite. He was in the West. That could happen here.

I

t was not long before Ry felt that the sun and dry air might be baking his brain. He thought he could feel it begin to shrivel and misfire, maybe even vitrify, inside his skull. But when he walked over to the river and waded in and splashed his face and stood in the shade for five minutes, his brain seemed to reconstitute and he could go on.

He came to a place where a road crossed the tracks, and he had to think, Road or tracks? Road or tracks? Tracks won because they looked straighter. Very, very straight.

On one of his forays into the river, something brushed against his leg as he stood there. He looked down to see a number of fish, each one about the size of his forearm, all swimming along. He didn’t know what kind they were. He fingered the pocketknife in his pocket and mentally pictured himself sharpening the end of a stick and trying

to spear one of the fish. He could picture sharpening the stick, but in his mind’s eye every time he took a stab, he either missed or just knocked the fish off course. How long would it take you, what was the learning curve on fish stabbing? Maybe he should give it a try while he still had strength. Then there would be the whole starting-afire-with-a-stick thing. Unless he ate the fish raw.

“I think you can go for pretty long without eating,” he said aloud. “As long as you have water to drink.”

He sat on the bank, putting his boots back on, and a white shape in the weeds caught his eye. He picked it up. It was the skull of a small animal. He laughed softly as a thought struck him. The thought was that he had expected to spend his summer hiking and looking for bones. He had wanted to do it because it seemed like it would be doing something real. And here he was, hiking, and here was a skull. And it all felt pretty real, right?

The difference was that instead of hiking with a small group of people and a guide who knew where to go, he was utterly alone and not one person in the entire world knew exactly where he was, including himself. And he hadn’t expected his hike to be along a railroad track.

But although the track didn’t make for the most interesting hike, it was not interestingness he needed

most. He just needed to get somewhere.

Ry turned the skull over and looked at it from various angles. What was it? Looking into its vacant eye sockets he said, “You were probably a large rodent. I’m guessing not that long ago.”

He held it in one hand as he got to his feet, then slipped it into a side pocket of his shorts. He would find out later what it was. It might be cool to put it on his dresser at home. The truth was that it made him feel a little less alone.

He took inventory of what else was in his pockets. It was a short list: pocketknife, next-to-useless cell phone, wallet. The list of what he didn’t have at the moment was longer.

“But at least I have my health,” he said. It was a joke.

The wallet had eighty-three dollars in it, a hundred bucks less the cost of some Amtrak food. He looked around for a place to spend it. “Where’s the 7-eleven?” he asked. This was a joke, too.

He said his lame jokes aloud, to keep his spirits up. He didn’t know if he should panic or not. Well—he knew he shouldn’t panic. But he didn’t know how dire his situation was. It was the moment when the elevator drops and you don’t know whether to laugh or get started on the screening of your whole life passing before your eyes. Only a lot longer than that moment. It was that moment stretched into hours.

Periodically, he felt the urge to text someone.

Nowhere

, he imagined typing.

Still nowhere.

Each time, without thinking, he pulled out his phone, looked at its blank face, remembered, and shoved it back down in his pocket.

“It’s not like I’m the only living thing, though,” he said. “Look. Cows.” Black ones grazed on a hilltop in the distance.

It was probably a great place to be a cow. Or a pheasant. One of which fluttered up from the grasses at his approach.

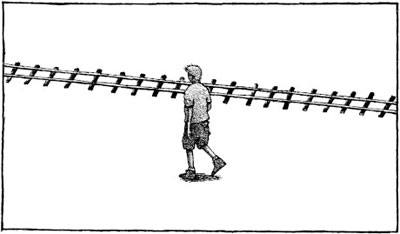

He walked past a field where cylindrical bales of hay were sprinkled like giant corks spilled on a tabletop. A dilapidated long-ago schoolhouse. A conglomeration of rusted buildings. A cluster of newer silvery ones. Ry stared for a long time at a small house painted bright orange with about twenty cars parked behind it, in varying states of decay, along with discarded bathroom fixtures and a windowless bus that seemed to have melted into the ground, faded to an almost greenish yellow, vegetation thriving around it and up through it. He decided to keep walking toward the little town.

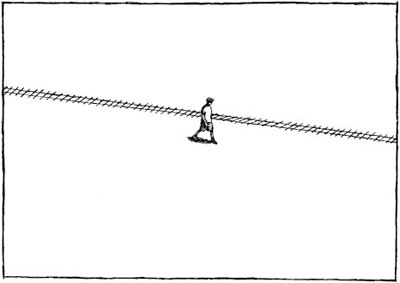

Down here in the bottomlands, Ry couldn’t see it. It had to be just beyond those next hills, though. Should he use his energy to climb up high again? What if night

fell before he got there? No. It couldn’t be that far. How often did trains come along, and would a train stop and pick up someone waving their arms? He didn’t think so. Would a train stop if the engineer saw a dead body near the tracks? Maybe the engineer would tell someone. But maybe he would be looking the other way.

The track split into two tracks now. That could be a good sign.

His stomach made the sound effect for a cartoon character hurtling through outer space in a spiral trajectory. The bones in his legs were softening into rubber bands. His forearms were covered with tiny scratches that were more painful than they looked.

Ry felt a sudden trickling from his nose, and then a flowing. He turned his head and lifted his arm to wipe it on the sleeve of his T-shirt and saw that it was blood. His nose was bleeding. Lifting the hem of his T-shirt and pinching his nose shut with it, he plodded along, breathing through his mouth, checking every few minutes to see if the bleeding had stopped.

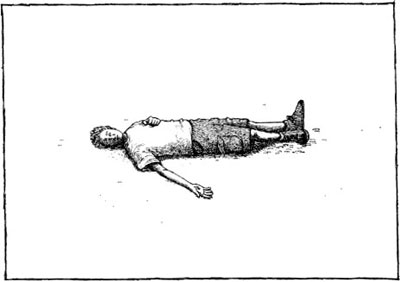

The sun was beginning to lower in the sky, shifting its strategy from beating down on his head and shoulders to blinding him. Ry started over to the river again and, without intending to, found himself sitting down halfway there. He

loosened the laces on his boots and then, without intending to, found that he was lying flat on his back. A large bird traced a silent circle high above. Was it a vulture, or a hawk? He wondered if he looked edible. He should not fall asleep out in the open. He was tired, though.

Vultures probably went by the smell. Of something rotting.

“It’s blood,” he said to the vulture, referring to his T-shirt, “but I’m not dead.” Still, maybe he should roll over closer to that tree. He was too tired to roll. He didn’t want to.

He pictured seasons going by as he lay there. Autumn leaves, covering him. They would have to blow over from those trees; the wind would have to be just right. Then the snows would cover him. By that time he would be picked clean. A skeleton, like the little creature by the river, now in his pocket. Probably some shreds of clothing would remain, fluttering in the frigid gusts of air. The little skull would lie next to his femur. Rest in peace.

The air had given up some of its heat. That was nice. A soft breeze floated over Ry’s closed eyelids. He dreamed he was lying on a bed. A huge bed; he couldn’t find the edges of it when he reached with his hands or his toes, but not a very comfortable one. Hard and lumpy. He must be in a motel room, because he became aware that the bed had a vibrating massage feature. Ry had heard about this, but he had never

seen one before. There was a metal box with a slot to put quarters in, to make it go. He was surprised at how loud it was, though—the loudness was canceling out most of the relaxingness. There was also a jerkiness to it, a stop-and-start irregularness, like trying to sleep when your neighbor was cutting up logs with a chain saw. He examined the metal box to see if he could adjust the setting, turn it down, but there were no knobs or dials, just the slot for quarters.

Then he sat up and opened his eyes.

A freight train was rolling by. It seemed to be slowing down; the sound of the steel wheels reached him in gently lurching waves as one by one the boxcars and tankers flowed along before him.

Ry thought he saw two figures, moving shadows, through the open door of a boxcar, and he saw that here was an opportunity for rescue. A way to shortcut his long hike. But the silhouettes gave him the creeps, too. And besides, most of the boxcar doors were shut.

He was on his feet now. He watched uncertainly for a time. The train seemed to be going slower and slower, slowing down to a complete. Stop.

Directly before him, a short set of metal steps led up to a metal mesh door in the metal mesh walls of a car carrier. If they hadn’t stopped so directly before him, beckoning

him, he probably wouldn’t have climbed on. But there they were. As if under a spell, he walked to them and hauled himself up. He climbed to the top step and tried the door. It was locked, so he turned around and sat down.

A few minutes later, there was a growing rumbling. When Ry stood up and leaned around, he could see between his car and the next that another train was passing in the opposite direction, on the second track.

Not long after the rumbling faded, his train began to move again. Slowly at first. Then continuing slowly. And slowly some more. The train never did move faster than very slowly while Ry was on it, because it was making its way onto a siding in a freight yard on the outskirts of the town. He had hopped onto the train just a mile or so out. He could have walked it, though he didn’t know that when he got on. He couldn’t see the town at the beginning of the track’s long, gradual curve. Even when he could see it, he was glad to be riding.

He rode with his legs stretched out, the backs of his heels resting against a lower step, watching this chunk of the world scroll by. When the train went over the river, on the trestle, Ry pulled his legs and feet up instinctively, uninstinctively forgetting how he had loosened his bootlaces earlier. His left boot caught on the edge of the metal step, his foot slipped

out of the boot, and the boot bounced once on the trestle and went sailing through the air, down into the milky coffee of the river water. He saw it reemerge to bob along downstream like a plastic duck in a carnival booth, way, way, way out of reach. He watched it in disbelief, his boot floating off to end up in some distant weedy backwater or at the bottom of the river, not doing anyone any good, while here was his foot in only a sock, his foot that the boot fit perfectly, never again to meet. He pulled the laces tight on the remaining boot and tied them.