Ardor (44 page)

Authors: Roberto Calasso

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

And so it might also be said: “It is only with the offering that a brick becomes whole and complete.” In those words we may find an answer to the question of what is the object of the gesture—an inevitable question, given such a profusion of liturgical gestures. An object—therefore also the object of knowledge—is never just that which is enclosed within a perimeter of matter or within the limits of a definition. To be complete, the object must also include within itself the gesture of the offering—and the entire liturgy is an immense variation on that gesture.

* * *

“The sacrificer being the sacrifice, he thus heals the sacrifice by means of the sacrifice.” Hidden in a sequence of invocations, we find an all-embracing formula, which describes the essence of that action—the sacrifice—which claims that it is everything. In this autistic and tautological vortex, only one word is added: the verb

heal.

The rest consists of grammatical variations on the word

sacrifice.

And if the verb

heal

is the only other word, this already indicates that everything proceeds around a wound, which coincides with life itself.

The sacrifice is a wound. Which has to be healed by inflicting another wound, but

in a certain way.

And, since wound is added to wound, the wound never closes. And so the sacrifice must be performed over and over again.

* * *

The sacrifice is an interrupted, incomplete suicide (Sylvain Lévi, with his masterly concision: “The only authentic sacrifice would be suicide”). But the ritualists were used to thinking to the extreme. What would happen if, on that journey toward the sky and coming back from the sky, which is the sacrifice, someone refused to

come back

? It would be a new rite, the

sarvasv

ā

ra

(the ritualists were relentless classifiers). A rite befitting an old man “who wishes to die.” It will begin with a series of actions and chants that make up the first part of the sacrifice, the part that moves toward the sky. When it is complete, the sacrificer lies down on the ground, with his head covered. Other chants follow. At the end of which the sacrificer

must

die. But if he doesn’t die? The ritualists also thought of this: “If he remains alive, he shall celebrate the last oblation of the

soma

sacrifice, after which he will seek to die of hunger.”

And there is yet one more eventuality: what if someone, before reaching old age, wishes to reach the sky through the sacrifice and not come back to earth? The ritualists advised against it: “People say: ‘A life of a hundred years leads to heaven.’ And so one ought not to yield to one’s desires and die before having reached the last term of life, for this does not lead to heaven.” And we know why: the gods don’t like intruders.

* * *

In thought, there is no evolution but rather an occasional concentration, accumulation, crystallization in particular places at particular times. For

ousía

, it occurred in Greece between the sixth and the fourth centuries

B.C.E.

; for

sacrifice

in India, between the tenth and sixth centuries

B.C.E.

; for

hunting

in certain tribes, in various parts of the world, we know not when. Each of these peoples was the most tenacious, most lucid, most obsessive in thinking about what is hidden behind those words. Then time served above all to unlearn, to obfuscate these elements of knowledge. But they remained there, waiting to be picked up once again, expanded, worked out, connected.

Sacrifice is a system that can have countless, uncontrollable variants. Always belonging to the same set. More than being a system, it is an attitude: the sacrificial attitude. It is to be found (or not) at every moment in a person’s life. And according to the teachings of the Br

ā

hma

ṇ

as, it is present throughout life, in its perpetual pulsation.

* * *

In the theories of sacrifice, after many twists and turns, we reach a final fork: either sacrifice is a device used by society to ease certain tensions or to satisfy certain needs, in which case it has to be said that it is a ruthless institution based upon a collective illusion that is perpetuated from generation to generation; or it is an attempt by society to blend with nature, taking on certain irreducible characteristics, in which case it must be seen as a form of metaphysics put into action, celebrated and displayed in a formalized sequence of gestures. In the first case, sacrifice would be an official part of society to be rejected without any second thoughts: a society that, in order to sustain itself, needs to choose arbitrary victims, simply because it

must

kill someone, is a society that no enlightened thinking could put forward as a model. In the second case, sacrifice would be a form of metaphysics to be refused or accepted. And an experimental form of metaphysics, based not just on certain propositions, but on certain acts.

* * *

Rudra is the most powerful objection to the sacrificial world of the Vedas. He accompanies it like a shadow, he watches its disruption. In the Black Age, that patient, noble work of sacrificial builders would no longer be feasible. Rudra, the nameless, was to become the ever-present

Ś

iva, already multiform in his names, ruler over every cult. For only

Ś

iva, as obscure as the primordial archer, the unnameable Rudra, resembles the obscurity of time. Only

Ś

iva can absorb time into himself—time which kills without remedy.

Desire, K

ā

ma, swirls about with his sugarcane bow and his five flower-arrows.

The only one who can reduce him to ashes is Śiva.

This was the obsessive thought: desire that provokes action, that produces fruits. One of these fruits is the world itself—its enchantment. The one who incinerates desire is therefore the destroyer of the world. But does this mean that

Ś

iva would become an enemy of desire? Such a conflict would be too simple, too crude. On the contrary:

Ś

iva is also the one who, more than anyone else, is susceptible to desire, who continually exasperates it, who pushes it to the extreme, who lets it run in his veins—to the point that sometimes we might think that

Ś

iva

is

desire, that

Ś

iva is K

ā

ma.

When Brahm

ā

curses K

ā

ma, he incites him to turn on

Ś

iva, because he knows that only

Ś

iva can crush K

ā

ma. In the same way that he knows that only K

ā

ma can wound

Ś

iva. By bringing K

ā

ma and

Ś

iva together, Brahm

ā

knows that in this way he can avenge himself against the one who has subjugated him (K

ā

ma) and the one who has mocked him (

Ś

iva). And he hopes they will torment each other endlessly, like two warring brothers.

XVII

AFTER THE FLOOD

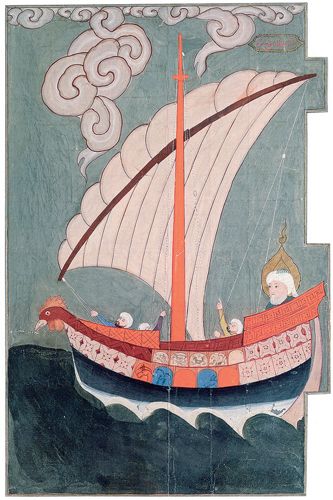

Noah left the Ark, obeying Elohim’s command. And with him all other creatures, one by one, countless pairs of animals of every species. Long processions, especially of insects. As many left the Ark as had entered, since none of them had had intercourse during the voyage. Intercourse was forbidden in times of calamity. And during the long months of the voyage, even death was held in abeyance, even for those whose lives were fleeting. Noah didn’t know what Elohim intended to do now. His last manifestation had been a disaster that had wiped away the land. And now his voice was inviting him to set foot once again on land that was barely dry. But what if Noah had got it wrong, from the very start? What if he himself had incurred the wrath of Elohim, as had happened to the rest of his generation? So Noah decided to do something that had never been done before. He built an altar. No more than a block of stone. But no one had thought of doing such a thing until that moment. Then Noah made a choice “among every clean beast and of every clean fowl” and killed them, beside the altar. Then he laid out the various pieces of flesh on the altar so that they burned completely. This is what we must assume, since the chronicler says that he “made holocausts rise on the altar.”

It was a strange, systematic slaughter of single animals. And their corpses were laid out on the same stone block. Yahweh was satisfied. The smell of the burnt flesh, horrible to men, was sweet to his nostrils. When Utnapi

š

tim did the same as Noah in Mesopotamia, after the flood, “the gods gathered like flies around the officiant.” Yahweh, on the other hand, did not move but began to think. He decided he would not “curse the ground any more for man’s sake.” Had his opinion of man perhaps changed? No. He thought then, as he had done before the flood, that “the object of man’s heart is evil from his youth.” This was how man was made. But this was no reason for man and the earth to be destroyed, as had almost just happened. Nevertheless, man had to follow certain rules. And his life had to undergo certain changes. First of all, from that day forth, men would inspire “fear and dread” in all creatures. This was itself something new, since, immediately before creating Adam, Elohim had thought only of offering him and his descendants “authority” over all the creatures of the earth. Between “authority” and “fear and dread” there was a distinct difference. But it was now the era

after the flood

—and this was a sign of it. Elohim then proclaimed another innovation: “Every moving thing that lives shall be food for you, like the green herb: I have given you all this.” Only one proviso was attached: “But you shall not eat flesh with its soul, which is the blood.” There were then a few words about killing. Any being that has killed a man—whether the killer is an animal or another man—would in turn be killed. We are not told by whom, hence it would not necessarily be revenge. The only certainty was that the killer would be killed, even if it was an animal that had killed a man. The killing of a human was a cycle from which there was no escape. And Elohim added: “For in the image of Elohim, Elohim has made man.” They were the same words that Elohim had thought before creating man, but which perhaps he had never spoken to him. About this, the chronicler doesn’t tell us. But those words are now spoken to Noah, immediately after the moment in which Yahweh had thought that “the object of man’s heart is evil from his youth.” And so that being which had been formed in the image of Elohim kept in his heart the desire for evil. Thus it was, and thus it must continue to be, thought Elohim. It was one of his thoughts that men most ignored.

In making his first “covenant” with mankind, Elohim limited himself to two actions: eating and killing. He made no mention of idols, adultery, stealing, or respect for parents, as if the only possible guilt serious enough to violate the covenant was centered on eating and killing. Eating also came within the sphere of killing, since Elohim now allowed flesh to be eaten. More precisely, the flesh of slain animals. But if the blood, being the soul, was eliminated from that flesh, then the killing would not have been a true killing. It involved Elohim in a line of reasoning that was very similar to that of certain Vedic ritualists in relation to sacrifice.

Finally, Elohim declared that the rainbow would be the seal of the covenant. It was a pact containing very few rules. When, over the years, Elohim felt the need to renew the covenant, all would be expanded. But for now, with Noah, he wished to add nothing else, as if those meager instructions included all the others that would be added in the future. In the first place, man was granted dominion over nature. He was allowed a surplus of force over all other beings. At the same time Elohim reserved life to himself. So man would therefore never be self-sufficient. So man could kill animals, but not eat their blood. So man had to perform sacrifices, because only after sacrificing had he become once again agreeable to Elohim. There was an obvious difficulty in these precepts, for man—in order to sacrifice as well as to eat—had to take the life of other creatures. But Elohim thought this could be overcome: to eat the flesh of animals, all that man had to do was drain the blood away. And in the sacrifice? Noah had celebrated a holocaust, where the animal was wholly consumed by fire. More than losing its life, it disappeared from the face of the earth—and passed on in its entirety to Elohim. For the moment, human life could proceed on that basis.

* * *

Anyone wishing to approach the phenomenon of sacrifice through the Bible will come up against two questions: why did Abel, “after a certain time” and after his elder brother Cain had offered to Yahweh “the first fruits of the earth,” wish to kill “the firstlings of his flock” to offer them with “the fat thereof” to Yahweh? And why did Noah, as soon as he set foot on dry land, want to kill examples “of every clean beast and of every clean fowl” to offer them to Yahweh?