April Queen (45 page)

Authors: Douglas Boyd

It was for Eleanor a brief reunion with her favourite son and Joanna, the daughter she hardly knew.

11

Four extremely busy days after arriving in Sicily, the situation in England caused her to set out on the homeward journey with letters from Richard appointing the Cornish-born Archbishop Walter of Rouen as replacement for the unpopular Longchamp, leaving Berengaria at Bagnara with Joanna as her chaperone. Something of their pointless existence is conveyed in the comment that they were as happy in each other’s company as ‘two doves in a cage’.

12

To get around the embargo on women accompanying the crusade by a technicality, they set sail eastbound three days later in advance of the main invasion fleet of 150 sailing ships and 53 galleys. Their vessel was a

dromon

– a fast Byzantine armed merchantmen with fore- and aftercastles, a lateen sail and fifty oars on each side, each rowed by one man. It had ample space for the considerable baggage of the two royal ladies and was escorted by two other vessels.

Leaving Sicily on 10 April, Richard’s fleet stopped over in Crete and Rhodes, probably to allow the horses to recover health and strength. Being unable to vomit during storms, many destriers were severely distressed on arrival in the Holy Land, suffering from the diet

of dry grain and stale water, and with muscular problems from being cooped up in stalls below decks.

13

Making landfall for the third time at Limassol on Cyprus, where the

dromon

carrying Joanna and Berengaria had been driven by a storm in which two English ships were crippled and pillaged by wreckers, Richard demanded reparation from Isaac Comnenus, the self-appointed Byzantine ‘emperor’ of the island.

When Comnenus refused, Richard unleashed his army in a blitzkrieg conquest of the island, whose grain harvest would go far to feed the hungry besiegers of Acre, themselves partly besieged by encircling Muslim forces. In a three-week campaign, he added the island to his other possessions. Taken prisoner, Isaac Comnenus’ daughter was placed in Joanna’s care as a hostage,

14

but it was not until 30 May – eleven months after the joint departure from Vézelay and ten days after Philip’s arrival at Acre – that her father surrendered, trusting Richard’s promise not to put him in irons. He was instead thrown into a dungeon, fettered with silver chains.

By then Richard was married at last, after putting off this duty of state until only a few months short of his thirty-fourth birthday. With Lent over and no shortage of priests and bishops to perform the ceremony, he could hardly delay any longer. Despite his cruelty and

the forbidden side of his life, Richard was devout. In order to take communion at the wedding he had to confess and afterwards expiate the sin of sodomy by being publicly flogged in his underwear. Given absolution after the act of contrition, he was united in matrimony to the hapless Navarrese princess who, on having a coronet placed on her head by the bishop of Evreux, became the first and only queen of England who never set foot in the country.

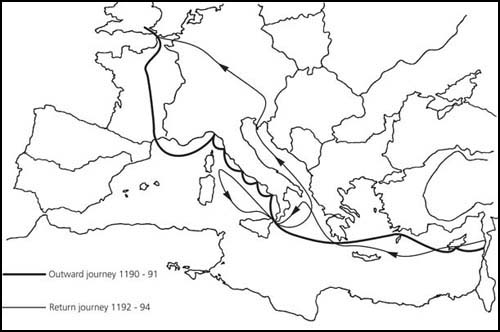

Richard’s route on the Third Crusade

The wedding ceremony took place in the small citadel chapel of St George. The bride’s appearance is a mystery, although we know the groom was magnificently attired in a rose-coloured

cotte

, embroidered with silver crescents that glittered in the sunlight, and a scarlet bonnet richly worked with figure animals and birds. His spurs were golden, as was the handle of his sword, and the mounts of his scabbard were silver. The saddle of his sleek Spanish charger also glittered with spangles.

15

All this splendour and display was, of course, illicit under his crusader’s vows. What the bride wore was seemingly of no interest to the celibate chroniclers, for no account survives. Whether or not the eight-year marriage was ever consummated remains as much a mystery as her appearance, for there was no issue. His crusader’s vow was not the only obstacle; although Richard had acknowledged paternity of a bastard by a serving girl in his youth, one bastard for a king who died aged forty-one was hardly proof of sexual prowess with women.

Among the wedding guests was the king of Jerusalem – none other than Guy de Lusignan, who had ambushed Eleanor when Patrick of Salisbury was killed twenty years before. Exiled by Henry, he had made his fortune in the Holy Land, where there was always a shortage of European warriors of suitable lineage due to the ravages of the climate, disease and the hazards of intrigue and combat. Following a similar path to that taken by Eleanor’s uncle, Prince Raymond of Antioch, he had married Sibylle, sister of the leper King Baldwin.

On Baldwin’s death, swiftly followed by that of his six-year-old son – due, some said, to poison – Guy’s wife had inherited the throne, making her husband king of Jerusalem. She and her two young daughters had died of disease while living in the siege camp outside Acre, leaving her widower with only a shaky claim to the throne.

16

Guy had therefore come to beg Richard’s support not against the Saracen, but because half the nobility of the Latin Kingdom supported his opponent Conrad of Montferrat. Impetuously, Richard espoused the Lusignan cause not only because Guy’s family were his vassals but because Philip had already endorsed Conrad of Montferrat’s claim to the throne.

Meanwhile, Eleanor was in Rome visiting Celestine III in her capacity as queen-regent of England, and making certain provisions that were to prove timely. It was not the first time they had met. Berengaria or not, she saw no reason to renounce her title, queen of the English, and it was thus she addressed the new pope on Easter Sunday, the day after his election. He was a former friend of Becket and student of Peter Abelard, whom she had known during her years on the Ile de la Cité as Cardinal Giacinto, or Hyacinth.

One of her requests was for the immediate consecration of Geoffrey the Bastard as archbishop of York, to stop him contending for the throne and complicating the Longchamp–Walter–Prince John situation. Her powers of persuasion led Celestine not only to acquiesce but exceptionally also give her Geoffrey’s

pallium

– the scarf of lamb’s wool that was a bishop’s badge of office, and which he usually had to travel to Rome to request in person.

Richard’s army anchored off Acre on 8 June. The city had been under siege for two years, for although Saladin was a brilliant general he was unable to stop the constant trickling away of the various Muslim contingents theoretically under his command and never had enough men at his disposal at any one time to mount a relief operation. The French were bearing the brunt of the fighting, along with what was left of the German army that had fought its way through Turkey under Frederik Barbarossa, reduced by many taking the opportunity to return home prematurely after his accidental death by drowning in the icy River Göksu.

Disembarking on 10 June, Richard found Philip ill from dysentery in the siege camp and suffering badly from the summer heat, which rendered even mail armour like an oven, despite the surcoats worn over them as insulation. After three months encamped outside Acre in the heat and stench caused by lack of sanitation, contagious infection and poisoning by unclean food was taking its usual toll of the Frankish besiegers. Some men had already been flogged for resorting to cannibalism.

17

In addition, Philip was depressed by the perpetual bickering of the various European contingents who on occasion cheered a telling blow by the enemy during a sortie, pleased that fellow-Christians of another language or country were in trouble.

Succumbing soon after his arrival to a bad bout of the malaria that had troubled him for years, Richard had himself carried on a litter from point to point, directing operations. With all his years of experience in the arts of war, he had made his preparations well. The latest models of prefabricated English and Poitevin siege-towers and catapults he had brought with him, with their jokey names like

Malvesin

or

‘Bad Neighbour’, were added to those already in position around the beleaguered city to ensure its rapid reduction. Far from welcoming this, his allies, who had spent a year and more blockading the city, resented the newcomers, whom they suspected of being likely to claim an inordinate share of the credit for victory. Continuing his policy of undermining Philip, who was paying three gold pieces per man per month to local reinforcements, Richard now poached them by offering four.

In company with Archbishop Walter of Rouen, Eleanor had obtained letters from the Pope demoting Longchamp from the status of prelate. Because of the delays of travel, it was normal to have several sets of letters to fit different circumstances on arrival. She also had letters from Richard to William the Marshal and the other justiciars covering just about every move that Longchamp or Prince John might make. After borrowing 800 marks from the Templars, or moneylenders, she left Rome with Archbishop Walter and journeyed north. Once through the Alps, he headed for England and she returned to Normandy, reaching Rouen on 24 June.

It is impossible to exaggerate the horror behind the sterilised accounts of medieval warfare. Outside the walls of Acre, the besiegers were fighting malaria and dysentery, typhoid fever from contaminated water and tick-borne typhus. Cholera might break out at any moment and rats feeding on the refuse brought the risk of plague. Night and day, the crusaders catapulted into the city missiles of stone and iron and fire, as well as living and dead prisoners and putrid carcasses of animals designed to spread disease among the defenders, who in turn operated counter-batteries of catapults, often returning the same missiles, and raining down on the attackers arrows, stones and fire.

At night the thudding of catapults and rams, the yells of exultation and screams of the wounded, prevented those who were not exhausted from sleeping.

18

The elegant pavilions of the nobles gave some respite from the clouds of flies breeding in the open latrines, and the sand flies and mosquitoes that bit every inch of exposed flesh, but many men slept in the open, even on the ground, despite the risk of scrub typhus.

Saladin sent heralds far and wide announcing the call to lift the siege, but his emirs refused to attack the vastly increased forces of the besiegers.

19

His inability to compel obedience was the crusaders’ most potent weapon. On 12 July the garrison, dying of thirst, surrendered in defiance of his orders after a last vain attempt by his nephew to fight a way through with a relief column.

The crusaders’ entrance into the city was marred by disputes over booty and fatal outbreaks of violence over rival claims to prestigious locations.

Philip’s Franks set themselves up in what had formerly been the Templars’ quarters, but when Richard’s contingent found themselves competing with the Austrians for the royal palace, an incident occurred which was to cost everyone in England dearly. The pennant of Duke Leopold of Austria, floating beside Richard’s standard, was torn down and cast by some unnamed Plantagenet knight or man-at-arms into the filth of the moat, used as an open sewer. Given the arrogance of Richard and his followers since their late arrival, the insult was taken as intended.

So bad was the relationship with Philip that, when his son and heir had been ill, Richard reportedly told him as a joke that the child had died.

20

Getting steadily sicker with scurvy from the vitamin-deficient diet, Philip had by now lost his hair and nails,

21

and was so weak that his advisers feared he was dying. From trench mouth or Vincent’s disease, he was also losing teeth. Ten days after the fall of Acre, a deputation of Frankish nobles came to Richard, begging him to release their king from the reciprocal oath to return home together. The scornful reply was that it would be a shameful thing to renounce the crusade before the liberation of Jerusalem, but if Philip’s life depended on it, he could depart.

22

With every penny spent, Philip now demanded a half-share in the loot from Cyprus to pay his homeward voyage,

23

to which Richard retorted that he wanted half of Flanders in return, Count Philip having died without heir soon after arriving at Acre.

24

Richard was touching bottom financially and anxiously awaiting the ransom money promised by Saladin for the 3,000 prisoners taken at Acre. On 31 July 1191 Philip set sail from Acre in a small squadron of Genoese galleys, putting in at Tyre before making his way through the pirate-infested Aegean islands via Rhodes and Corfu, where he waited for a safe-conduct from Tancred of Sicily and the German Emperor to pass through their territories.

Back in the Holy Land, Richard was enjoying his now undisputed position as the leader of the crusade, and counting among his forces 10,000 Franks left behind under Hugues de Bourgogne.

25

They proved to be a mixed blessing because they had to be fed and equipped, for which he was relying on the arrival of the 200,000 dinars that had been demanded for the garrison’s ransom, of which Philip had renounced his share.