April Queen

Authors: Douglas Boyd

To all our tomorrows: Chloe, Edward, Eleanor, Eve, Gwyneth, Hannah, Jessie and Lily

Vivant in pace!

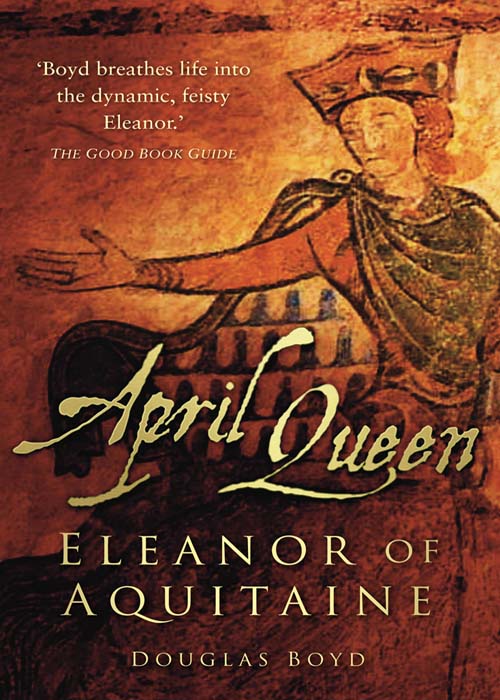

Cover Illustration:

detail of twelfth-century fresco showing Eleanor of Aquitaine and her son Richard the Lionheart, Chapelle Ste Radegonde, Chinon, France (

author’s photograph

).

List of Illustrations and Maps

2

Mistress of Paris, Aged Fifteen

5

Crusading Fever Sweeps Europe

6

Luxury in Constantinople, Massacre on Mount Cadmos

7

Accusation in Antioch, Joy in Jerusalem, Defeat at Damascus

Appendix A: The Search for Eleanor’s Face

Appendix B: Eleanor’s Poetry and Song

M

y thanks are due to Friedrich Heer, who shone Burckhardt’s light into many dark places of history; to my Gascon friends Nathalie and Eric Roulet, at whose home in Les Landes I first heard Occitan as a living language; to Eric Chaplain, managing editor of the Occitan publishing house Princi Neguer in Pau, for lending precious source material that saved both travel and much sitting in libraries; to Alain Pierre for keeping Occitan alive and making me probably the only author ever interviewed live on radio in that language; to fellow-author and horsewoman Ann Hyland for equestrian advice; to Dr Harold Yauner for his medical knowledge and many jokes; to Jennifer Weller for maps, seals and photographic help; to portraitist Norman Douglas Hutchinson for bringing his demon’s eye to bear on Eleanor’s likenesses; to Valérie de Reignac of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs de Bordeaux; to Caroline Currie for photo-reconnaissance; to Gabor Mester de Parajd of Les Monuments Historiques; to Les Amis du Vieux Chinon for permission to photograph the fresco in the Chapelle Ste Radegonde; to the staffs of La Bibliothèque Nationale, the British Library, the Public Record Office and the Bibliothèque Municipale de Bordeaux for their anonymous work, so vital to writers and scholars; to my partner Atarah Ben-Tovim for unflagging companionship in Eleanor’s footsteps in Europe, Turkey and the Levant; to ‘Biggles’ Turner for piloting my airborne camera platform G-AYYI; and to Elizabeth Stone and Sarah Flight at Sutton Publishing for their skill in making a readable book from so many pages of text and images.

To my agent Mandy Little I owe thanks especially for placing this book with Jaqueline Mitchell at Sutton, who treated the author as a long-distance swimmer tugged repeatedly off-course by fascinating currents of research, and repeatedly showed him the way to landfall. In this time of corporate publishing, that is rare. To Jaqueline, my deepest thanks.

Black and white plates

1 Mystery girl at Fontevraud, Eleanor or Blanche?

2 The hidden head, Bordeaux Cathedral

3 Eleanor in her early twenties, Chartres Cathedral

4 Henry’s prisoner: Eleanor aged fifty-two

6 Eleanor and Louis in the Portail Royal, Chartres

7 The golden Virgin of Beaulieu

9 Geoffroi de Lauroux at the wedding in Bordeaux

10 Henry’s father, Geoffrey the Fair

11 Eleanor’s state apartments in the Maubergeonne Tower, Poitiers

12 The audience hall, Poitiers

13 The porch of Poitiers Cathedral

14 Twelfth-century floor tiles from Aquitaine

15 Altar cross in Limoges enamel from La Sauve Majeure

16 Fresco in St Radegonde chapel, Chinon

17 Henry triumphant (fresco detail)

18 Eleanor hands the gyrfalcon to Richard (fresco detail)

19 Eleanor’s sons desert her (fresco detail)

23 The Lionheart’s effigy, Fontevraud

24 Berengaria’s effigy, L’Epau

25 Isabella of Angoulême’s effigy, Fontevraud

26 Effigy of Eleanor’s son John, Worcester Cathedral

27 The Plantagenet effigies, Fontevraud Abbey

28 The nuns’ kitchen, Fontevraud

29 Effigies of Eleanor and Henry, Fontevraud

Eleanor’s inheritance: Poitou and Aquitaine

Eleanor and Louis on the Second Crusade

Eleanor’s and Henry’s combined possessions on 19 May 1152

Was this Henry’s grand design?

Richard’s routes on the Third Crusade

Introduction

W

hen the occasional lists of the all-time rich and powerful are compiled by the media the name of Eleanor of Aquitaine is almost always present. The London

Sunday Times

in its list of the ‘50 Richest Ever’ labelled her the richest woman of all time. In its survey of the 100 most important people of the second millennium

Time

magazine dubbed her ‘the most powerful woman’ and ‘the insider’ of her century.

Charismatic, beautiful, highly intelligent and literate, but also impulsive and proud, Eleanor inherited just after her fifteenth birthday the immense wealth and power that went with the titles of countess of Poitou and duchess of Aquitaine. From that moment she played for the highest stakes, often with the dice stacked against her, until her spirit was finally broken by the death at the siege of Châlus of her favourite son, Richard the Lionheart. Neither before nor since has one woman’s lifetime been more crowded with excess of wealth and poverty, power and humiliation.

Although she was born in 1122 and died in 1204, this mysterious figure who was uniquely both queen of France and of England did not conform to preconceptions of medieval European womanhood. Raised in the Mediterranean troubadour society that esteemed amorous adventures, verse and music on a par with prowess at arms, she scandalised the tonsured schoolmen who wielded much political power in the north of France by her liberated behaviour and thinking. Even after two of her great-grandsons were canonised as St Louis of France and St Ferdinand of Spain, nothing could persuade the Church to reappraise its first judgement of her as a young whore who became an old witch. Borrowing plot and characters from the chronicles, four centuries after her death Shakespeare unkindly labelled her in his play

King John

a ‘cankered grandame’.

The first European poet since the fall of the Roman Empire was her crusading troubadour grandfather, Duke William IX, whose verse

was philosophical but also amorous and full of humour – as befitted a man whose mistress was called La Dangerosa! The troubadours, male and female, depicted women as sensual, empowered beings and not sinful chattels whose only proper function was childbearing, and the ideal of courtly love associated with Eleanor and her daughters was in that tradition.

At a time when even monarchs rarely set foot outside their own kingdoms in peace and few women except noble and royal brides ever left the country of their birth, she travelled extensively on both sides of the English Channel and much farther afield, seeing for herself the squalor of medieval Rome whose citizens had recently killed a pope, the decadent glory of Constantinople and the ugly truth behind the romance of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Returning from the Second Crusade after a year as prisoner of her estranged husband Louis VII of France, she was hijacked by Byzantine pirates and forced by Pope Eugenius III to share Louis’ bed against her will.

Like materials, people reveal their qualities when tested nearly to destruction; the courage of this extraordinary woman is best exemplified at the time her fortunes hit an all-time low. In 1173 the armed rebellion of her three adult sons by the marriage to Henry of Anjou was defeated by his swift and ruthless counter-offensive. Her one chance of escape lay in throwing herself on the mercy of his greatest enemy – Louis, the first husband whom she had tormented and divorced.

Betrayed to Henry by men she trusted in her own household when within a few leagues of safety on Frankish territory, she knew that he would pardon his sons but deal with her more harshly. Her death would permit him to remarry and sire more legitimate sons, playing them off against the first brood in his usual fashion with the threat of a punishment or the promise of a bribe that was never honoured. Yet, unless in one of the berserker rages that betrayed his part-Viking ancestry, he would not kill her for fear of losing her dowry of Poitou and Aquitaine. In addition, another murder would not go down too well in Rome so soon after being flogged in his underwear by monks at Canterbury Cathedral and Avranches as penance for his part in Becket’s death.

On the other hand, the pope would grant him an annulment if asked, for the degree of consanguinity was even closer than that which provided the spurious grounds for her divorce from Louis. However, that solution would also involve handing back her dowry

of Poitou and Aquitaine – and Henry never gave anything back, not even a son’s rejected fiancée whom he kept as his own mistress.

Eleanor knew exactly what lay ahead. Henry was eleven years her junior, a man in his prime who would never forgive her. He would allow her the illusion of freedom from time to time – an appearance at an Easter or a Christmas court, some cloth for a new dress or the privilege to go riding each morning, or to have books. But each carrot would be withdrawn when she refused to bite, and the stick would be used again harder than before.

Accustomed as she had been from birth to the luxury of good food and fine wine, fashionable clothes, amusing company, literature, poetry, music and dancing, how long could a queen live, deprived of all this and her liberty and dignity too? She was already fifty-two, in a time when most women died young in childbirth or from overwork or disease. To Louis of France she had borne two daughters. To Henry she had given five sons and three daughters to use as pawns in marriages arranged to seal the knots of alliances.

Judged by any standards, Eleanor had already lived a remarkable life. Born under the Roman laws of Aquitaine, which did not disqualify the female line from succession, she was raised to inherit the duchy after her only legitimate brother’s early death. This made her a teenage multi-millionairess, who married a crown prince and became queen of France two weeks later. Was that not enough glamour for one lifetime?

Not for Eleanor. Her years with Louis included rumours of scandalous love affairs in Paris and in the Holy Land on the Second Crusade. Divorcing him, she twice escaped kidnap and rape on the flight to safety in her own domains. There followed her years as duchess–queen of the Angevin Empire, on the move with Henry’s court as he crossed and recrossed the Channel to bring his restless magnates to heel as only William the Bastard had done before. How many women, or men for that matter, have lived such adventures and come home to tell the tale?