April Queen (2 page)

Authors: Douglas Boyd

When Henry discarded her at the menopause, she revived the civilised lifestyle of her own court at Poitiers, where art glorified love and praised womanhood – and where she was effectively queen in her own right, not a mere consort. Yet she risked everything in an intrigue worthy of the Roman Empress Julia to unite in rebellion three sons who detested each other as much as they hated their manipulative and brutal father. Why? And why, on being taken prisoner by him, did she not accept the honourable alternative he offered, and which most women of her class and age would have preferred: to renounce

her titles and retire to a convent? Frustratingly for the historian, during her fifteen years as Henry’s captive she had all the time in the world to dictate her memoirs but was deprived of secretary, quill, parchment – and at times of everything else except food.

On Henry’s death, she returned to the world stage aged sixty-seven as vigorous physically and mentally as any man or woman of half her age, demanding her jailer’s obedience by declaring herself still the crowned queen of England and thereby regent for her son Richard the Lionheart. Armed initially only with her own willpower, she governed England until he arrived and for much of his reign.

Her great moment of glory came at his coronation in Westminster Abbey, where the new monarch, who had no place in his life for women and certainly not for a wife, installed her as his dowager queen. This adored son of hers was among the worst rulers the realm would know, twice milking it dry of taxes in a ten-year reign, of which only a few months were spent in England – a country he despised, and whose language he never learned. Yet of all its kings, he alone has his statue in Westminster Square at the seat of government.

The crusades are no longer seen as a glorious episode in European history, yet for cinema and television audiences he remains King Richard of the Last Reel, heroically returning in the last minutes of the film from a mysterious Outremer to vindicate loyal Robin and his merry men and put the villainous supporters of his usurping brother John in their proper place. That web of myth, obscuring the terrible reality of what was called ‘knightly warfare’, has stood the test of eight centuries because it was spun by his mother as PR to drag out of an exhausted and over-taxed empire the enormous ransom demanded for his return from captivity, against the opposition of Prince John in league with King Philip of France, and the many Anglo-Norman barons who preferred to keep Richard locked up in Germany.

Rightly trusting no one else to conclude the deal, Eleanor then risked piracy on the high seas to convoy in person the thirty tons of ransom silver to Germany, bringing her son home after out-bluffing the Emperor, who had been offered bribes to renege on the bargain. To do all this in her mid-seventies tells us what strength of purpose she had, even then.

Why then have historians treated her so meanly?

The misogynistic Pauline clerks who penned the chronicles that are our primary sources polarised women as Eve or the Virgin Mary. For them, a woman as powerful and impious as Eleanor

was

Eve incarnate, and thus the cause of all man’s sin and suffering. The influential clerics

with whom she fearlessly crossed swords while queen of France – from the ascetic St Bernard of Clairvaux and the great statesman Abbé Suger to the Templar eunuch Thierry Galeran – did their best to thwart her in life; the chroniclers merely continued the character assassination after her death.

But surely historians take such bias of primary sources into account?

Friedrich Heer, Professor of the History of Ideas at the University of Vienna, was trained as a historian in the Swiss tradition of Burkhardt. He observed that his colleagues educated in the Rankean nineteenth-century German system of cause-and-effect, were so intent on fitting events into ‘logical’ sequences and making each one appear to have been inevitable that they snipped the pieces of the jigsaw to make them fit into what seemed evidence of a Divine Plan, with the steady hand of God ultimately in control of man’s actions.

So it was for Ranke’s British followers, including Bishop William Stubbs (1825–1901), whose influence on the teaching of medieval history at British universities lasted into the second half of the twentieth century. If history were made logically, then every human event would be predictable. But it isn’t. Making it appear so requires distortion of inconvenient happenings and sidelining history’s losers, of whom Eleanor was one of the most magnificent. It is significant that the first modern biography of her – Amy Kelly’s

Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Four Kings

(Harvard, 1950) – appeared as Stubbs’ influence was at last waning.

Heer offered a second reason why his academic colleagues had devoted scant space to this queen of France and England in their writings. Although her lifetime, spanning four-fifths of the twelfth century, fell within the academic province of European medievalists, he considered them ill equipped by their training to understand this transitional period when feudalism had many forms, monarchy was experimental, the concept of nations had not crystallised and frontiers were permeable by pilgrimage and trade, even between Christian and Moor. In the throes of an economic and cultural transition, Europe was then awash with revolutionary ideas and the new music, poetry and technology brought back by pilgrims, merchants and crusaders who had travelled to the East. Nowhere was this truer than in Aquitaine, so near in spirit and geographically to the light of Moorish Spain and so far from the gloom of Capetian Paris.

Herodotus’ original concept of

historia

was not the recital of dates and battles, but the gaining of knowledge by enquiry. Happily, in recent years medieval history has evolved, thanks to cross-fertilisation

with other academic disciplines and the expansion of women’s studies, which throw a different light on Eleanor’s lifetime. Yet her biographers since Amy Kelly have produced little new information about Eleanor, her husbands and children – and failed to explain why she chose repeatedly to pursue her own path at such great cost to herself.

In part, this is because documentation of the early twelfth century is sparse, compared with the later Middle Ages, so that the chronicles touch on Eleanor largely through hearsay tainted by scandal. In part, it is because women’s lives – even queens’ lives – were ill documented, compared with those of male contemporaries. In addition, there has been a tendency by Anglo-Saxon writers to treat her as a ‘French’ duchess, when she was effectively the queen by birth of a people who differed from the Germanic Franks in the north of what is now France by racial origin, language, culture, lifestyle and a whole system of values. Some English-speaking biographers have also betrayed an ignorance of even modern French, let alone Old French, Latin and Eleanor’s first language, Occitan – all of which are necessary to demystify this important historical figure.

Work on this biography began a quarter-century ago when I bought a partly medieval stone farmhouse in south-west France, where the local post office is in a castle built by Eleanor’s son John, of Magna Carta fame. Being bilingual in English and French, my ear was caught by the different usage and

accent chantant

of the locals, so different from the northern

accent pointu

which I and most foreigners learned in school. It was like being in the Highlands or Wales or Ireland, where Celtic people speak English with the cadence of their own language and using figures of speech that sound merely picturesque to outsiders but are the echo of its emotionally richer and more expressive idiom.

At that time the grandparental generation in the villages here still spoke what northerners despise as

patois

, meaning ‘the speech of those little better than animals’. Properly called Occitan or

la lenga d’oc

by those who speak it, it had been stubbornly giving ground during a century of prohibition in schools, where children were beaten for using the tongue they spoke at home. Since then, the media have achieved what the whip and the rod could not, killing a living language in less than two generations.

As a Scot, I sympathised with a people whose culture was being strangled by a more powerful neighbour. As a linguist I became fascinated by the language of the troubadours, which evolved from Latin so rich in shades of emotion and rhyming possibilities as to be the ideal tool of a civilisation to which the whole of Europe owes an

inestimable debt for producing the first flowering of the Renaissance and influencing all European lyric poetry since.

Banned from public use in France by François I early in the sixteenth century, Occitan changed so little that studying the everyday speech of my elderly neighbours was the vital first step to understanding Eleanor’s own language as she knew it and reading first hand the thoughts and feelings of her contemporaries and intimates. This in turn has opened windows into her values and her world that were closed to previous biographers.

Douglas Boyd

Gironde, south-west France, 2004

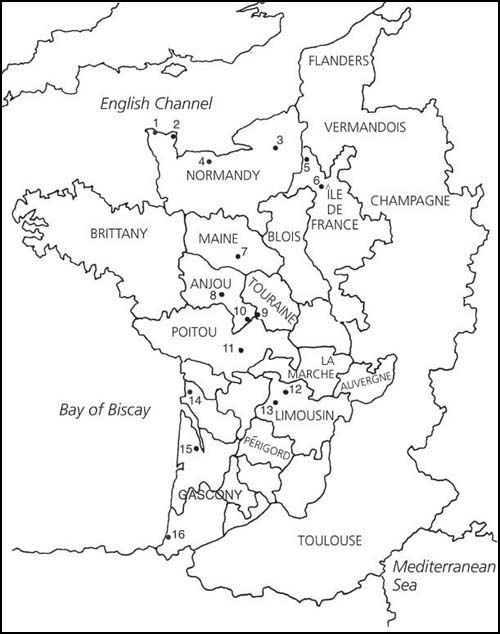

France in the twelfth century.

The Aquitaine Succession

E

leanor was just fifteen years old in May 1137. At an age that was considered adult for either sex she had the poise and confidence that came from having ridden with her father Duke William X

1

of Aquitaine for hundreds of miles in the same direction without meeting a soul who did not owe him allegiance. She was beautiful, she loved music and dancing, poetry and song. In a time when few men and fewer women could read, she was also literate in three languages and mature beyond her years.

Eleanor’s grandfather had used force of arms to weld the dissident barons of south-west France into a restive aristocracy that acknowledged his authority, but he had also been the greatest European poet since the fall of Rome, whose verses were declaimed and sung from the Atlantic to the Holy Land and beyond. A man of many contradictions, he had been the most courteous of suitors but also a great seducer of women. He had both defied the Church and been on crusade to Jerusalem.

But her father was an unlettered warlord, who had spilled so much blood on campaign in Normandy the previous year that he had set out from the abbey of La Sauve Majeure on Easter pilgrimage to the holy shrine of Santiago de Compostela

2

in Spain to purge his soul. This was in preparation for marrying the widowed daughter of his vassal

Viscount Aymar of Limoges in response to his counsellors’ urging that it was time to ensure a male heir for the rich county of Poitou and the vast duchy of Aquitaine.

Eleanor had passed the weeks since his departure with her younger sister Aelith in the ducal palace of L’Ombreyra at the south-east corner of the city of Bordeaux, two teenagers amusing themselves in the huge warren of apartments, audience chambers and tiled courtyards shaded by fig and olive trees. Aelith was two years younger, but both sisters were aware this would be Eleanor’s last springtime of freedom before an arranged marriage to some rich and powerful prince. With their mother and brother dead and their father absent, the girls were flattered and courted by the young unattached knights of the ducal court, while minstrels sang with lute and lyre their grandfather’s praises of women and love.

In the north, such behaviour would have been considered scandalous intimacy. Here it was one of the normal pleasures of life. And the scandal was that the duke’s betrothed had been carried off by a neighbouring baron and forcibly married in his absence – a deed that would cost him dearly when William X returned.

3

Then, at the beginning of May, everything changed. Maidservants came running through the palace with news that the knights who had accompanied Duke William X on his pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela had posted in haste past the monastery at Cayac and the great abbey of La Sainte Croix south of the city without stopping to give alms to the monks at the wayside. Once within the gates of Bordeaux they had ridden straight to the archiepiscopal palace in the south-west corner of the city, where they were closeted with the most powerful man in Bordeaux, the newly appointed Archbishop Geoffroi de Lauroux. But of Duke William there was no sign.