And the Band Played On (29 page)

Read And the Band Played On Online

Authors: Christopher Ward

On Saturday the

Standard

published its correction, carefully pitched by Mr Dickie to save his neck.

The story of the Dumfries nurse named Grace Hume having been brutally murdered at Vilvorde by German soldiers has proved to be a malicious invention. The letters given to the press by Miss Kate Hume and published on Wednesday are forgeries and the Scottish Office are instituting an inquiry as to their origin.

The

Standard

report, which ran to over a thousand words, made it sound as if its own wide-ranging investigation had exposed the truth of the matter and reunited Grace with her father and stepmother.

We regret that the publication of the forged letters should have been the means of harrowing the feelings of our readers. But it is satisfactory to know that the appearance in ‘The Standard’ was the occasion of the immediate exposure of the imposture and of putting her family in communication with the young woman within a few hours and thus relieving anxiety regarding her fate which they had endured for days.

For good measure, the

Standard

even threw in an apology to the German army: ‘It is satisfactory to know that the character of the German soldiery has been saved from this foul stain.’

Although she was the innocent party in the hoax, Grace Hume must have felt compromised, for she wrote to her father that day from her lodgings at 62 Trinity Street, Huddersfield, to assure him that she had nothing to do with it:

Dear Father,

I am sorry you have been made miserable over the false report. I knew nothing about it until yesterday when I saw placards in the town . . . it is an absolute mystery to me. I neither know, nor yet have I heard of such a person as Nurse Mullard, neither have I been out of Hudd since war was declared . . .

I am very sorry that you should be put to any trouble and inconvenience at all but I hope you will understand that it is as much a worry and a trouble to me as well. The person who concocted the tale undoubtedly knows all about us . . .

Yours,

Grace

For the first time, the authorities started to take an interest in the affair. This was not good news for Kate, who had never wanted the story to go any further than George Street. The War Office had already been alerted by Andrew’s letter asking for news about his daughter, and the Scottish Office, concerned about the murder and mutilation of one of its citizens abroad, fired off a dozen letters. The Foreign Office was asked to make enquiries about the mysterious Nurse Mullard in Belgium. The Lord Advocate in Edinburgh asked the Procurator Fiscal in Dumfries for a full report. The Procurator Fiscal instructed Dumfries police to make enquiries – the Chief Constable of Dumfries, Mr William Black, heading the investigation himself. Nothing less than a prosecution followed by a public trial would satisfy the authorities: they wanted someone’s head on a plate.

The full force and fury of the state and the law now turned on Kate Hume, an unhappy seventeen-year-old girl who had staged a silly hoax in order to hurt her parents. The police investigation quickly established that Nurse Mullard was not a German agent but a fiction of Kate’s fertile imagination. When interviewed, Kate admitted forging the letters and, asked why she had done it, replied, ‘To hurt my father and stepmother.’ It should have ended then and there. But no one had thought to advise the police, before they commenced their investigation, on what crime Kate was supposed to have committed. She had certainly caused everyone a lot of trouble and she had forged two letters, but she had not done it for personal gain – her only motive was to annoy her parents. As one of the investigating officers observed, if that was a crime, then Scotland’s prisons would be full of teenagers, including his own daughters.

The Chief Constable, having now interviewed Kate himself, consulted the Procurator Fiscal because he felt that, unless ‘felonious intention’ could be proved, Kate had not been guilty of any crime. The Procurator Fiscal then consulted the Lord Advocate who had no doubt at all what Kate should be charged with. Kate’s actions were a clear contravention of Section 21 of the Defence of the Realm Regulations 1914, an emergency Act that had been introduced a month earlier to protect Britain at war. Anyone charged with an offence under the Act would face a military trial by court martial. The maximum sentence was death by hanging or firing squad.

The Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) gave wide-ranging powers to the government for the duration of the First World War. It included bans on flying kites, lighting bonfires, buying binoculars and, even more bizarrely, feeding bread to wild animals. Its principal objective was to keep morale at home high and to prevent people from passing on information that might assist the enemy. In their wisdom, the various authorities believed that Kate had indeed assisted the enemy and she was duly charged at the end of September and held in police custody. The police, in accordance with the provisions of the Act, then contacted the military authorities at Hamilton where, it was proposed, she would be imprisoned pending her court martial. The police would provide the necessary evidence for her trial.

The military authorities at Hamilton – busy training soldiers for war and at the same time rounding up drunkards and deserters – didn’t at all like the idea of keeping a seventeen-year-old girl in their cells, court-martialling her and then possibly standing her blindfolded against a wall and shooting her. They started looking at the small print of DORA and decided that the regulations only applied in ‘Proclaimed Areas’ within the meaning of the Act. Dumfries did not constitute a proclaimed area, whereas Vilvoorde did. As Kate had never been to Vilvoorde and neither had her sister Grace, Hamilton made the strongest of polite protests to the Lord Advocate, asking him to review the decision.

The Lord Advocate asked a distinguished King’s Counsel, Mr J. Duncan Millar, Liberal MP for North East Lanarkshire, for a second opinion. Mr Millar agreed, in a private memorandum, that a charge under DORA might be difficult to sustain and that a safer course was to press charges of forgery in a criminal court. As a result, the charge against Kate was amended to ‘concocting and fabricating’ letters and forging signatures ‘with the intent of alarming and annoying the lieges, and in particular your father Andrew Hume and your stepmother Alice Mary Hume, both residing at 42 George Street, Dumfries’. Kate was remanded in custody to Edinburgh prison.

Soon afterwards, the Lord Advocate received another opinion – a rather more unwelcome one but also given in private – this time from the Solicitor General, Sir Thomas Brash Morison. He wrote expressing his concerns about charging Kate with anything: ‘A difficulty might arise at the trial from the preposterous nature of the story . . . I have doubts whether anyone at all seriously believed it (the hoax).’

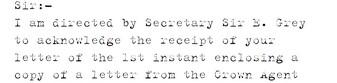

Meanwhile, in spite of Kate’s confession, the police went about their business of gathering evidence for the prosecution. Handwriting experts were called in to compare Kate’s handwriting with that of ‘Nurse Mullard’ and forensic examination of plain sheets of paper found in Kate’s office revealed that they had a similar composition and texture to the paper that ‘Nurse Mullard’ had used to write to Kate. In all, twenty-two witnesses were interviewed, including her father and stepmother who were to give evidence for the prosecution. However, there was one major obstacle that still had to be overcome. The police had great difficulty in establishing beyond any reasonable doubt that Nurse Mullard did not exist, and this was a fundamental pillar of the prosecution case. While the War Office was fairly certain that there was no one called Nurse Hume on the casualty lists, they had no way of knowing if there was, or wasn’t, anyone called Nurse Mullard helping at the Front. Indeed, they had little idea of what was going in Vilvoorde, having had difficulty at first even in ascertaining where it was. The Crown Agent for Scotland started applying pressure in Whitehall to answer the question, provoking a flurry of letters between the Foreign Office and the War Office. On 6 November, even as thousands of troops were taking up their positions in trenches and as Vilvoorde was being shelled by the Germans, Ralph Paget, Assistant Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, found time to write to the Secretary to the Army Council as follows:

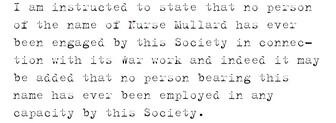

In the end, the Red Cross came to the rescue. After a month-long investigation in Belgium and a thorough search of filing cabinets in London, Frank Hastings, Secretary of the British Red Cross Society, wrote to the War Office: