An Old Heart Goes A-Journeying (5 page)

Read An Old Heart Goes A-Journeying Online

Authors: Hans Fallada

In which Professor Kittguss pays a call that ends in a coalshed

B

ELLO, A SHAGGY SHEEPDOG

, was not really a very formidable animal, and he was now fawning and whimpering at Rosemarie’s side. The child firmly led her godfather by the hand through an unlighted room, full of the moldy reek of potatoes and the damp odors of a sink. Then she suddenly left him alone in a small, dismal, green-painted kitchen and vanished through a door behind which children’s voices raised a shrill clamor.

“Rosemarie!” cried the Professor.

“Marie, you little devil!” screamed a rasping woman’s voice from the corner of the hearth—and broke off abruptly.

Catching sight of the visitor the speaker turned on him sharply. The reflection from the kitchen lamp shone upon her pale face, her large brown eyes, and prominent cheekbones. It was a young face still, but the narrow, almost lipless line of her mouth looked old and evil, and her jutting chin was hard and resolute.

“Hullo!” cried the woman in her rasping voice as she eyed the belated visitor without moving from her seat.

“God be with you!” replied the Professor, advancing a step. “I am Professor Kittguss and . . .”

“And,” pursued the woman, overwhelming the Professor with a savage tirade, “if you’re from the Welfare Office, you’ve no business to come at such a time. I won’t show you the children today. The folks in the village can write to you all they like about the way we ill-treat the children, and starve them and neglect them, and you can set that sniffy old Welfare sister after me every week and every day and every hour, or you can come yourself, if you like. . . . A Professor, are you, eh? Well, you earn your keep by sitting down while I wear the flesh off my bones washing those little bastards’ filthy napkins for thirty marks a month! But I won’t show you the children today if you stay till midnight, now the girl’s off on the loose. I’ll show her the right end of the broomstick when she gets back. The folks round here are a bad lot, and they want to make everybody like themselves. You better come tomorrow morning about ten, and then you can see all the five little rascals, all neat and clean—unless one of ’em goes and makes a mess at the last moment—”

At first the Professor tried to stem the torrent, then he stood and listened patiently, feeling just as shocked and grieved as he had when Rosemarie burst out at him beside the fence. But when Frau Schlieker had finished, he went up to her, stretched out his hand, and said: “God be with you, Frau Schlieker.”

She eyed the hand in bewilderment, as though it had

struck her. Then she took it, growling: “Good evening, but you must go now.”

“No,” he persisted, his hand still outstretched. “I said—‘God be with you.’ That means something else.”

A few moments of silence followed. The Professor kept his frail hand still outstretched. At last she laughed, a harsh and awkward laugh. “All right, then: God be with you.” And for an instant she touched the Professor’s hand with chill damp fingers.

“But you must go now. I haven’t got so much time as you have. I’ve got five brats to look after.”

“And the sixth is Rosemarie,” said the Professor gently. “Did you mean Rosemarie, when you talked of the girl who had gone off on the loose?”

“Oho!” snarled the woman, back in her venomovs mood. “You want to know about Marie? Why did you behave as though you came from the Welfare Office, when you come from the Guardians, eh? We’re not afraid of a magistrate

or

a policeman, I’ll have you know! And if the brat’s been writing lies to you, my husband will show her the sort of hand he writes. I dare say you know the old saying: ‘Parsons’ kids are as bad as millers’ cows. . . .’ ”

She ran to the kitchen window: “Paul! Paul! Come at once. There’s company!”

Then, without pausing for breath, she continued her tirade. “And whatever I called her, I stand by what I said—there’s nothing much here that’s hers except debts. My old man and I can work till we’re dead just to provide her with her dinner, and us with five bastard brats to look after. All this to earn enough to keep my fine

young lady warm inside and outside in the winter—and not a pennyworth of thanks from anyone. Paul, here’s someone from the Board of Guardians asking after Marie.”

A tall red-haired man, still comparatively young, had entered the kitchen, carrying a bucket of milk. Smiling politely at the visitor, he said: “Well, Mali, now you’ll have to put the milk through the separator.”

“Me,” cried the woman, “with all I’ve got to do, and the girl out on the rampage all the afternoon—and you having a nap on the sofa? Ah, Paul, if the constable could get hold of Philip, I’d give him such a welcome home!”

“Ssssst!” said Paul, so abruptly that the Professor started. “Hold your tongue and see to that milk before it’s cold.”

Even the Professor noticed that the tall, amiable man now looked extremely forbidding. The woman picked up the pail and slunk out of the kitchen.

Presently Herr Schlieker recovered his good humor. “This way, please. There’s no fire in the parlor and you must take us as you find us. We’re poor folk, but we’re honest: we don’t steal wood out of the forest like some people I could mention. We’d sooner freeze ourselves, so long as the children’s room is warm. . . . Just wait here a minute. I’ll fetch the lamp. Keep quite still. It’s a bit dark, and the trapdoor to the beet cellar just behind you is open. Don’t move a step or you’ll fall into the hole, and the cellar’s pretty deep.”

The door clicked, and the old Professor was left standing in the darkness, bag in hand. For a long, long while

he stood there, not daring to lift his foot for fear of the open trap. . . . Surely there had been time to fill and trim and light twenty lamps. Moreover, kindly as the Professor was, he had not been taken in by the amiable Paul, who struck him as a two-faced rascal, and though he detested ill-natured gossip, that remark of Rosemarie’s kept recurring to his mind. “And,” thought the Professor, “I know from my old friend Fritz Reuter that a Schlieker’s a crook. . . . Dear, dear me,” the Professor exclaimed aloud in a sudden surge of disgust, “this is certainly no place for me—I must get home at once. But the child—that poor neglected child—she talked of setting the house on fire! No, I must stay and see it through. . . .”

At this point the farmer reappeared with the lamp.

“I’ve been quite a while, haven’t I? Yes, the gentry don’t like waiting, but a poor man has to run a long way before a rich man needs to get up. I had to feed the pigs: we’re only countryfolk here, sir, and animals come first. And you’ve been standing here like an image and I didn’t have the sense to remember that it’s old Pastor Thürke’s study, and of course there isn’t a trapdoor—Well, you as a learned gentleman know what it is to be a bit absent-minded, don’t you?—so I dare say you won’t be too hard on a poor chap like me?”

The Professor paid little heed to the man’s unctuous chatter. He had been looking about: the room was indeed a parson’s study, not unlike his own, with a standing desk and a writing desk, a green plush sofa in the corner, and a mahogany table in front of it. He lowered himself slowly on to the sofa and eyed with rather gloomy eagerness the bookshelves that lined the walls.

It went to his heart to see the books lying in confusion, dusty and neglected, with great gaps here and there, and some actually dropping out of their bindings.

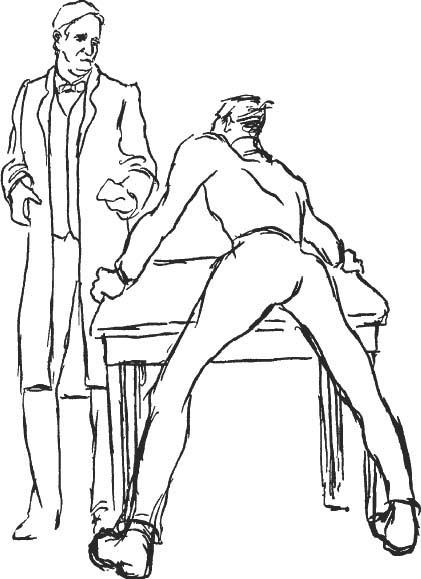

The Professor faces Paul Schlieker down

.

But for all his weariness, he felt at home in that derelict abode of learning, and he said to his host: “Pray do not talk to me like that, Herr Schlieker. I quite understand that my presence here is unwelcome. As soon as I know what is the matter with Rosemarie and how I can help her, I will trouble you no more—I shall go away.”

“Ah,” said Paul, thoughtfully rubbing his chin and gazing fixedly at the Professor, “so Marie’s been at it again, has she, writing to the Board about the wicked Schliekers, eh? Well, the Guardians can’t have much to do if they listen to what a child says without questioning me or the magistrate.”

“Not at all,” replied the Professor hastily. “Your wife misunderstood me, Herr Schlieker. I do not come from the magistrate or the Board of Guardians. I am Professor Gotthold Kittguss, of Berlin.”

The other went on rubbing his chin, as though he were rubbing a smile into his large and increasingly foxy countenance. “Who would have thought it?” he murmured. “So it’s not an official at all.” He leaned across the table and looked the Professor closely in the eyes. “But you are related to Marie, eh? You’re some sort of relative?—”

The Professor did not quail before that smiling, staring face: “No, I’m an old school friend of the late Pastor Thürke, and I want to . . .”

He stopped, for the other had flung the table aside and now faced him, fists clenched and flushed with fury.

“And you come here,” he shouted, his voice rising to a shriek of rage, “you come here without a shadow of right or claim. You raise a row in my house, you set the little beast against us, making her worse than she is already. Blast your professorship, I’ll kick you out of this house, you old ruffian! I’ll break all the bones in your body if I catch you here again, you . . . you. . . .”

Paul Schlieker really looked as though he were going to assault the Professor, and he stopped roaring only for a moment to get his breath.

Old Professor Kittguss may have feared dogs, rats, frogs, and various harmless beasts, but he had no fear of man. Slowly and with deliberation he rose from the sofa and gazed benevolently at the infuriated figure before him. Then he laid one firm gentle hand on his adversary’s shoulder, and, pointing with the other to his chest, said: “You’ve got a pain there, Herr Schlieker, I fancy? It is the evil spirit of anger within you, giving you pain. Until you cast it out you will never be happy. And you surely want to be happy?”

The other tried to shake off the old man’s grip, and for a moment he seemed about to strike his chest. But that he could not quite do, though he freed his shoulder from the old man’s feeble fingers. Paul Schlieker stepped back before the large brown eyes that seemed to look right through him, straightened his jacket, and said gruffly: “You’re just a silly old fool, that’s what you are. . . .”

“And, Herr Schlieker,” continued the Professor quite unperturbed, “that same evil spirit of anger makes you say things you don’t mean. You say you’ll set the dog on me, and break every bone in my body. You say that

sort of thing, but you don’t mean it. And why don’t you, Herr Schlieker?” asked the Professor, eying his adversary. “Because, fundamentally, you are a good man.”

“Well!—” gasped Paul, utterly dumfounded. Many things had been said to him in his life—indeed, there was hardly any abuse that he had not endured—but this had never been said to him before.

“Well,” he blurted out at last. “It’s no use talking sense to such a man. Tell me what you really want, or I’ll never get you out of the house, I can see that.”

“I want to look after my friend’s child, Rosemarie, Herr Schlieker,” said the Professor.

“Ho!” jeered the other. “And what do you want to look after? Her bit of property—the shanty here with thirty-five acres? Well, we’re looking after that, and doing a good job. I send in the accounts to the Board once a year, and they’ve never found anything to howl about yet.”

“If you are looking after Rosemarie’s earthly inheritance,” said the Professor, “I have no wish to interfere, and I am quite satisfied. But what of her heavenly inheritance?”

“Well, Herr Professor,” laughed Paul Schlieker, noticeably relieved. “Although my Mali and I are just simple folk, we aren’t heathen, and we say our grace before dinner and supper. But Marie don’t care about that sort of thing: you won’t find a more obstinate and defiant little girl in the whole village.”

“I don’t believe you,” said the Professor. “I knew my dear friend Thürke, Rosemarie’s father, very well, and there couldn’t have been a better or a kinder man. I knew his wife Elise too, and though it might be said

that she lived in a world of fairy tales and miracles, and knew no more of this life than a child, there’s a saying that an apple doesn’t fall very far from the tree. I dare say it’s true enough in this case, so will you be so kind as to go fetch the child, Herr Schlieker? I have only seen her in the dark, and I should like to see my friend’s daughter where it’s light, and talk to her and ask her a few questions in your presence.”

“She’s got no time now,” growled Herr Schlieker. “She’s been gallivanting around the whole afternoon, and now she’ll have to do her work.”