An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism: The Essentials of Buddhist Spirituality (30 page)

Read An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism: The Essentials of Buddhist Spirituality Online

Authors: William Stoddart,Joseph A. Fitzgerald

Tags: #Philosophy

96

An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism

Green Tārā, Mongolia, early 18th century

Tibet

97

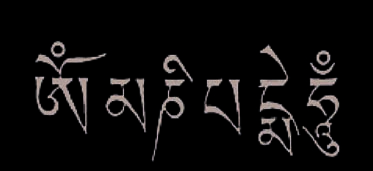

the emptying of the mind of worldly things, invocation is the filling

of the mind (and heart) with a revealed Divine Name and its saving

grace.

The masculine and feminine principles of

tantra

are present in the

Names contained in the

Mani-Mantra

,

the central invocatory prayer

of Tibetan Buddhism, namely,

Om Mani Padme Hum

: “O

Thou Jewel

in the Lotus, hail.” The Jewel may be interpreted as Avalokiteshvara

(the Bodhisattva representing the Buddha’s Mercy or Compassion)

and the Lotus as his feminine counterpart Tārā. The Lotus (

padma

)

is

the existential or “horizontal” support for the “vertical” or “axial”

Jewel (

mani

).

The Lotus is thus the symbol of the pure and humble human soul

(viewed as feminine and “horizontal”) that opens out its petals (i.e.

acquires the fundamental spiritual virtues) so that it may attract, and

become the fitting vehicle of, the Jewel of Buddheic grace (viewed as

masculine and “vertical”). This symbolism is identical to that of weav-

ing, in which the weft (horizontal) and the warp (vertical) are in the

same “sexual” relationship to one another. “Weaving” is in fact the lit-

eral meaning of the word

tantra

.

There is an obvious analogy between the Tibetan formula and sim-

ilar invocatory prayers in other religions, such as

Sītā-Rām

in Hindu-

ism and

Jesu-Maria

in Catholicism.

As indicated in the table on the preceding page, the union of the

“Subject” with the “Object”, of the Invoker with the Invoked, of the

Lover (masculine) with the Beloved (feminine) results in

Ānanda

or

“Bliss”. In Buddhist

tantra

this spiritual union is called

Mahāsukha

(“the Great Bliss”). This is symbolized in Tibetan art by the tantric stat-

ue of

Yab-Yum

(literal y “father-mother”), which portrays the loving

union of the masculine and the feminine principles.

The

mantra

Om Mani Padme Hum

(“O Thou Jewel in the Lotus, hail!”)

98

An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism

His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama,

lama tulku

of Avalokiteshvara

Take heed of the lives of the saints, the law of karma, the miseries

of worldly existence . . . , the certainty of death, and the uncer-

tainty of the time of death. Weigh these things in your minds,

and devote yourselves to the study and practice of Remembrance.

Milarepa3

3 In the above quotation, Remembrance means “remembrance of the Buddha”

(

Buddhānusmriti

) through the way of invocatory prayer (

mantrayāna

).

Tibet

99

iv. The Panchen Lama and the Dalai Lama

In order to understand the roles of the Panchen Lama and the Dalai

Lama, it is necessary to take into account the “celestial principles” (i.e.,

the Buddha or Bodhisattva) which they represent. These are respec-

tively Amitābha Buddha and Avalokiteshvara. (See the tables on pp.

72-73.)

Amitābha Buddha is the Buddha (or Aspect of the one and uni-

versal Buddha) who presides over the “Western Paradise” (i.e. the state

entered by those who achieve salvation through the invocation of the

Name of Amitābha).

Avalokiteshvara (known as “Chenrezig” in Tibetan) is the Bodhi-

sattva who represents one of the main qualities of Amitābha, namely

Mercy or Compassion. Avalokiteshvara is said to emerge from the

forehead of Amitābha.

A

lama tulku

is

a human being who has the function of incar-

nating a “celestial principle”. (The various

lama tulku

s

are sometimes,

perhaps misleadingly, referred to as “Living Buddhas”.) The Panchen

Lama, whose traditional residence is in Shigatse, is the

lama tulku

who

incarnates Amitābha (the Buddha of the “Western Paradise”). The Da-

lai Lama, whose traditional residence is in Lhasa, is the

lama tulku

who

incarnates Avalokiteshvara (the Bodhisattva of Mercy or Compassion).

Since Avalokiteshvara is hierarchical y inferior to Amitābha, the

Dalai Lama is hierarchical y inferior to the Panchen Lama. But this

does not detract from the importance in practice of the Dalai Lama,

who has the specific function of “Protector of Tibet”. He fulfil s this

function, not merely by being both temporal ruler and supreme reli-

gious authority, but also by exercising what is known in the Buddhist

world as an “activity of presence”. As

lama tulku

of

Avalokiteshvara

or Chenrezig (the Bodhisattva of Compassion), the Dalai Lama is the

incarnation of this “celestial principle”, and through him, it radiates,

protectively, over the Tibetan people and their religion. It is this “activ-

ity of

presence” that is the essential role of the Dalai Lama.

The office of

lama tulku

of Chenrezig is transmitted from one Da-

lai Lama to the next by means of a certain traditional process which is

described by Heinrich Harrer in his book

Seven Years in Tibet

.

If the Dalai Lama possesses the providential function of Protector

of Tibet, it may be asked why it was possible for him to be displaced

from office, expelled from Tibet, and for his country and religion to

have been ravaged by the Chinese communists. The answer to this is