An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism: The Essentials of Buddhist Spirituality (29 page)

Read An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism: The Essentials of Buddhist Spirituality Online

Authors: William Stoddart,Joseph A. Fitzgerald

Tags: #Philosophy

Rinchen Zangpo (tenth century) [“the Great Translator”]

Atīsha Dipamkara Shrī Jñāna [Indian] (eleventh century)

Koncho Gyepo Khön (eleventh century)—

Sakya

order—“Gray Earth”

Tilopa [Indian] (tenth century)

↓

Nāropa [Indian] (eleventh century)

↓

Marpa (eleventh century)

Kagyü

order

[“the Translator”]

↓

&

Milarepa (eleventh century)

Karma-Kagyü

order—“Black Hats”

Tsongkhapa (fourteenth-fifteenth century)—

Gelug

order—“Yellow Hats”

He who knoweth the precepts by heart, but faileth to practice

them, is like unto one who lighteth a lamp and then shutteth his

eyes.

The Ocean of Light for the Wise

Tibet

93

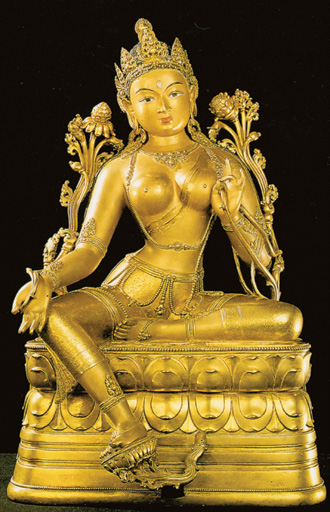

iii. Tantra

In Buddhism, there are not only the

Hīnayāna

and

Mahāyāna

schools.

There is also a branch of

Mahāyāna

,

namely

Vajrayāna

or

Tantrayāna

,

which, because of its importance, is called the “Third School” or the

“Third Setting in Motion of the Wheel of the Law”.

Vajrayāna

spread

from India to Tibet in the eleventh century, and became of particular

importance in the latter country.

Buddhism in general looks on the world as an exile; it sees it under

its negative aspect of corruptibility and temptation—and so of suffering.

Tantra

,

on the contrary, sees the world positively as theophany or sym-

bol; it sees through the forms to the essences. Its spiritual way is union

with the celestial archetypes of created things. In the words of Frithjof

Schuon: “

Tantra

is

the spiritualization—or interiorization—of beauty,

and also of natural pleasures, by virtue of the metaphysical transpar-

ency of phenomena. In a word:

Tantra

is

nobility of sentiments and

experiences; it excludes all excess and goes hand in hand with sobriety;

it is a sense of archetypes, a return to essences and primordiality.”2

The metaphysical doctrine and spiritual practice of

tantra

is

based

on the masculine and feminine principles or “poles”, known in Vedānta

as

purusha

and

prakriti.

In Hinduism, these are represented or symbol-

ized by Shiva and his Consort (

Shakti

)

Kali. In

Mahāyāna

Buddhism

in general, and in Tibetan Buddhism in particular, the masculine and

feminine principles appear in the form of the following pairs:

Masculine

Feminine

Upāya

(“Formal doctrine and method”)

Prajñā

(“Formless wisdom”)

Vajra

(“Lightning”, “Diamond”)

Garbha

(“Womb”)

Dorje

(“Thunderbolt scepter”)

Drilbu

(“Handbell”)

Mani

(“Jewel”)

Padma

(“Lotus”)

YAB (“Father”)

YUM (“Mother”)

intellectuality

spirituality

2 Unpublished text, no. 1042.

94

An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism

This polarity (and its resolution) evokes the doctrine implicit in one of

the Hindu names for God, namely

Sat-Chit-Ānanda

,

often translated

as “Being-Consciousness-Bliss”.

In divinis

this Ternary means “Object-

Subject-Union” and, spiritual y or operatively, it can be rendered as

“Beloved-Lover-Love” and other analogous ternaries:

Sat

Being Object Beloved Invoked Known

Chit

Consciousness Subject Lover Invoker Knower

Ānanda

Bliss Union Love Invocation Knowledge

In this context, the first row is seen as the “feminine” element

(

prajñā

),

the second row as the “masculine” element (

upāya

),

and the third row as the union between them (

sukha

).

Metaphysical y, it can be said that

samsāra

(the world) “is”

Nirvāna

(the Divine State). This is because Reality is one, and the Principle of

samsāra

is

Nirvāna.

Also, and for the same reason, the distinction can be

bridged in unitive prayer: “The Kingdom of Heaven is within you.” For

fallen man, however, the situation is quite different:

samsāra

is very far

from

Nirvāna

.

Hence the Buddha’s central message: “I teach two things,

O disciples, suffering and release from suffering.” In theistic terms, one

can say that existence, by definition, involves separation from the Divine

Source. God created the world so that “other-than-God” could know

Him. The purpose of existence is precisely the work of return; were it

not so, existence would have no meaning. This work is compounded

of faith and prayer, and rendered possible by the saving grace of the

Avatāra

.

In

Vajrayāna

Buddhism,

tantra

is the Way of Return.

The operative side of tantric doctrine resides essential y in the invo-

catory spiritual method (

mantrayāna

)

referred to on pp. 79-80, namely

Buddhānusmriti

(“remembrance of the Buddha”). In Christianity, the

analogous method finds its scriptural basis in the text “Whoever shal

call upon the Name of the Lord shall be saved” (Romans,

10:13). This

practice takes the form of the constant or frequent invocation of a sa-

cred formula or

mantra

,

the sacramental power of which derives from

the Name (or Names) of the Divinity which it contains. If meditation is

Tibet

95

T’hanka

of Guhyasamāja, a form of Akshobya Buddha,

in union with his consort Sparshavajrā, Central Tibet, 17th century