An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism: The Essentials of Buddhist Spirituality (18 page)

Read An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism: The Essentials of Buddhist Spirituality Online

Authors: William Stoddart,Joseph A. Fitzgerald

Tags: #Philosophy

holds in thral . On the contrary, “higher

Māyā

”—mediated and made

accessible by divine revelation, as well as by inspiration and intellec-

tion—is liberating and saving. In Christian terminology, it is the dif-

ference between Eve and Mary. In Buddhism, it is suffering and release

from suffering.

The Founders of the great religions are incarnations of the

Logos

—

levels (2) and (3).4

Of what use are words of wisdom to a man who is unwise?

Of what use is a lamp to a man who is blind?

Dhammapada

4 For a very clear explanation, see Frithjof Schuon,

Form and Substance in the Religions

, chap. 5, “The Five Divine Presences” (Bloomington IN: World Wisdom, 2002).

52

An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism

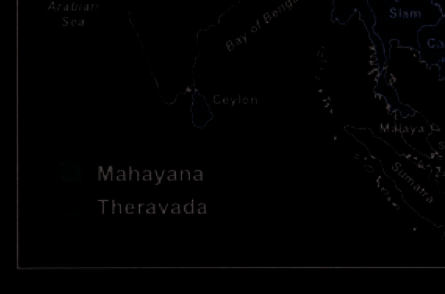

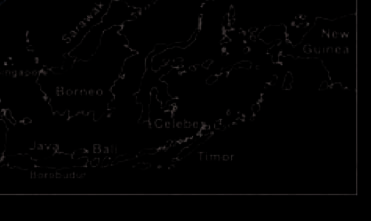

Map of the Buddhist World

(circa 1900)

The map below indicates virtual y all of the countries which comprise

the Buddhist area of the world

53

(9) The Two Schools and the Two Cultural Forms

In the face of a reformed and reviving Hinduism and the irruption

and expansion of Islam, Buddhism began to decline in India in the

seventh century A.D. and by the thirteenth century had become virtu-

al y extinct in the land of its birth. It spread, however, to almost all of

Eastern Asia.

A few centuries after its birth, Buddhism began to crystallize

into two great schools, the Southern and the Northern. The Northern

school or

Mahāyāna

(“Great” or “Broad” Way), which began to take

form towards the beginning of the Christian era, called everything that

came before it

Hīnayāna

(“Smal ” or “Narrow” Way). Although the

term

Hīnayāna

has been applied diminishingly, it refers in a positive

sense to the original monastic or ascetic Way, and is not in itself dis-

paraging. The

Hīnayāna

school had many branches or sects, including

Theravāda

,

Mahāsānghika

,

Vātsīputrīya

,

and

Sarvāstivāda

.

Of these only

Theravāda

(the “Doctrine of the Elders”) survives. The Southern

school,

Hīnayāna

(in fact

Theravāda

),

comprises Ceylon (Sri Lanka),

Burma, Siam (Thailand), Cambodia, and Laos. The Northern school

Mahāyāna

,

comprises China, Tibet, Ladhak, Nepal, Bhutan, Mongolia,

Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.

The

Mahāyāna

and

Hīnayāna

art styles—as well as the two cultures

in general—have distinctive and recognizable “flavors”. In this connec-

tion, Frithjof Schuon has al uded to a certain ethnic and spiritual reci-

procity by observing that, in the

Mahāyāna

countries, Buddhism has

been absorbed by the “Yellow” genius, whereas in the

Hīnayāna

coun-

tries the “Yellow” genius has been absorbed by Buddhism. Metaphori-

cal y speaking, the

Mahāyāna

world is India become “Yellow”, whereas

Hīnayāna

Buddhists (e.g. the Theravādins of Indo-China) are “Yellow”

people who have, as it were, become Indian.1

It may be of interest to note in passing that the only Buddhist com-

munity in Europe are the Kalmuks, a Mongol people who, in the sev-

enteenth century, migrated westward from Central Asia to Russia—to

the region now known as Kalmykia, on the north-western shores of the

Caspian Sea between the Muslim regions of Astrakhan and Dagestan.

Theravāda

Buddhism is a continuation of original Buddhism, as

regards its form if not as regards its whole content.

Mahāyāna

Bud-

1 See Frithjof Schuon,

Castes and Races

(London: Perennial Books, 1982), p. 43, note 31.

54

An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism

dhism also derives from original Buddhism, but some of its charac-

teristic manifestations spring from a later inspiration. In some of its

aspects an influence from Hinduism is discernible.

The Scriptures of original Buddhism are recorded in Pali (a de-

rivative of Sanskrit), and this language remains the liturgical medium

of the Southern (or

Theravāda

) school. The original scriptural and li-

turgical language of the Northern (or

Mahāyāna

) school is Sanskrit,

but, in view of the geographical extension of

Mahāyāna

,

this is supple-

mented by Tibetan, Chinese, and Japanese. For more on the Scriptures,

see pp. 16-17.2

Mahāyāna

Buddhism, the second “Setting in Motion of the Wheel

of the Law” (

Dharmachakra-Pravatana

), is

characterized above all by

the doctrine and cult of the Bodhisattva

(see pp. 67-70 and 77). Fur-

thermore, in

Mahāyāna

countries, Buddhism general y finds itself in

a state of co-existence or symbiosis with one or more indigenous reli-

gions. In China, Buddhism co-exists with the “esoteric” and spiritual

(and yet, at the same time, popular) doctrine and traditions of Taoism,

and also with the “exoteric” and social (and yet, at the same time, aris-

tocratic) doctrine and traditions of Confucianism. In Japan, Buddhism

co-exists with Shintoism; in Tibet, it co-exists with Bön.

As can be seen from the table on page 10, Taoism, Confucianism,

Shinto, and Bön are branches of Hyperborean shamanism. Unlike the

various Aryan and Semitic religions, shamanisms are not “denomina-

tional” and exclusive. Thus, while it is impossible to be a member of

two different “denominational” religions at the same time, it is per-

fectly possible to be a member of a shamanistic and a denominational

religion at the same time. One sees this, precisely, in the case of the

Chinese, Japanese, and Tibetans, and also in the case of many Red In-

dians, who see nothing untoward in belonging to a Christian denomi-

nation while, at the same time, believing in and practicing the religion