An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism: The Essentials of Buddhist Spirituality (10 page)

Read An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism: The Essentials of Buddhist Spirituality Online

Authors: William Stoddart,Joseph A. Fitzgerald

Tags: #Philosophy

Some Early Buddhist Figures

21

Ashvaghosha

(first-second centuries A.D.)

Ashvaghosha was born into a brahmin family, but was converted to

Buddhism by a Buddhist monk. He wrote in Sanskrit, and was a poet,

dramatist, and musician. He was revered as a “sun that il uminates the

world”. Original y from Eastern India, he settled in Benares. He was

the earliest and greatest philosopher of the Northern School of Bud-

dhism, and reputedly the author of the classic work “A Treatise on the

Awakening of Faith in the

Mahāyāna

” (

Mahāyāna-Shraddhotpāda-

Shāstra

).

This was translated into Chinese in the sixth century, and is

renowned in China and Japan. He wrote in verse a life of the Buddha

(

Buddha-charita

)

from his birth to his

Parinirvāna

(“final expiration”).

He was the 12th Indian patriarch of

Dhyāna

Buddhism, and probably

the guru of Nāgārjuna, the 14th patriarch.

Nāgārjuna

(second-third centuries A.D.)

Nāgārjuna was one of the most celebrated of Buddhist scholars and

teachers. He was born of a brahmin family in South India, and early

in life acquired great learning. He converted to Buddhism, took mo-

nastic vows, and mastered the

Hīnayāna

canon. Later he went to the

Himalayas, where he assimilated the

Mahāyāna

sūtras. He thus en-

compassed in his person both the

Hīnayāna

and the

Mahāyāna

teach-

ings. He was outstanding as a philosopher, and the doctors of the Bud-

dhist university of Nālandā in Bihar claim him as their forefather. He

was a prolific author, much of his work interpreting and expounding

the

Prajñā-Pāramitā-Sūtra

.

He was the founder of the

Mādhyamika

(“Middle Way”) school of

Mahāyāna

Buddhism and also the 14th In-

dian patriarch of

Dhyāna

or Zen.

Vasubandhu

(fourth-fifth centuries A.D.)

Vasubandhu was born in Purushapura (now Peshāwar) in the ancient

north-west Indian province of Gandhāra. He lived for some years in

Kashmir and died in Ayodhyā in what is now Uttar Pradesh. He and

his brother Asanga, along with Maitreyanātha, were the founders of

the

Yogāchāra

(or

Vijñānavāda

)

school of

Mahāyāna

Buddhism, for which one of the most important scriptures is the

Lankāvatāra-Sūtra

.

(

Yogāchāra =

“Teaching of Union”;

Vijñānavāda =

“The Way of Dis-

crimination”.) Vasubandhu was the 21st Indian patriarch of

Dhyāna

.

22

An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism

Buddhaghosha

(fourth-fifth centuries A.D.)

Buddhaghosha was born into a brahmin family who lived near Bodh-

Gayā. He converted to Buddhism and migrated to Ceylon, where he

took up residence in the Mahāvihāra monastery at Anurādhapura. He

identified completely with the

Theravāda

school and wrote important

commentaries in Pali on the

Tipitaka

.

His main work was “The Way of

Purity” (

Visuddhi-Magga

).

Bodhidharma

(fifth-sixth centuries A.D.)

Bodhidharma was the son of a South Indian king. He converted to

Buddhism, and was the disciple of Prajñādhara, the 27th Indian pa-

triarch of

Dhyāna

Buddhism. He eventual y became his successor, the

28th patriarch. In 520 A.D. he went by ship from India to China. There

he traveled widely, teaching the Buddhist doctrines. He was received

in audience by the Emperor Wu-ti of the Liang Dynasty, who was a

patron of Buddhism. Bodhidharma became the first patriarch of

Ch’an

(

Dhyāna

)

Buddhism in China. He remained in that country until his

death.

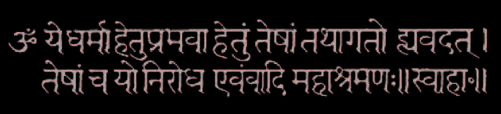

Sanskrit Buddhist text in Devanāgarī script

(calligraphy by Shrī Keshavram Iengar):

“Of all things springing from a cause,

the cause has been shown by him ‘Thus-come’;

and their cessation too the Great Pilgrim has declared.”

Saddharma-Pundarīka-Sūtra

, 27

23

(7) Buddhist Art

It is not the purpose of this book to deal with the immense, variegated,

and wonderful world of Buddhist art,1 but, in view of its importance,

passing mention should perhaps be made of three important early

schools.

Firstly it must be understood that, like all sacred art, Buddhist art

is of supernatural origin: it derives from the Buddha himself, and is

an integral part of the Buddhist sacramental system. It is said in the

Divyāvadāna

that King Rudrāyana (Udāyana) of Kaushāmbī sent

painters to the Buddha in order to paint an image of him which the

faithful could venerate in his absence. When the painters failed to cap-

ture his essential form, the Buddha said that this was due to their spiri-

tual lassitude. He then ordered that a canvas be brought to him, and he

projected his similitude upon it.

According to the seventh century Chinese monk Hsüan-Tsang,

King Udāyana had an image of the Buddha made in sandalwood dur-

ing the latter’s life-time and this became the prototype or model for

innumerable later copies.2

Buddhism, therefore, like Hinduism and Christianity, is “incarna-

tionist” and “iconodulic”.3 In this it contrasts with Judaism and Islam,

which are “non-incarnationist” and “iconoclastic”. According to Bud-

dhist doctrine, “the Buddhas also teach by means of their superhuman

beauty”. This explains why the magnificent iconography of Buddhism,

a veritable “outward sign of inward grace”, plays such an important sac-

ramental role. An icon (

pratīka

)

“objectivizes” a transcendent principle

which, in the worshiper, becomes a “subjective” state. In this way, the

icon is a vehicle of spiritual realization. The same idea finds expression

in the Platonic doctrine that “beauty is the splendor of the true”: truth’s

radiant beauty, made visible in sacred art, has the power to transform

hearts and save souls.

1 For an excellent exposition of the spiritual meaning of Buddhist art, see

Sacred Art in

East and West

by Titus Burckhardt (Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, 2001).

2 See

Elements of Buddhist Iconography

by Ananda Coomaraswamy (Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press, 1935), p. 6.

3 In Christian theology, a distinction is made between

latreia

(“worship”—due only to

God) and

dulia

(“veneration”—due to saints, relics, and icons). Hence “iconodulia”

(which is legitimate) and “idolatry” (which is illegitimate).

24

An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism

In statues and paintings, the Buddha is always depicted in a par-

ticular posture or with a particular gesture of the hands. These bodily

poses or attitudes are known as

mudrā

s,

and derive from the Hindu

tradition, having been revealed in the

Bharata-Nātya-Shāstra

.

They

symbolical y represent certain aspects of the Buddha’s actions (e.g.

preaching), doctrines (e.g. the Four Noble Truths), or radiance (e.g.

protective blessing). They may also represent spiritual perfections or

inward states of soul. In the case of Buddhist worshipers,

mudrā

s

may

sometimes accompany the recitation of prayers or

mantra

s.

Lovers of

Hindu dancing (

bharata natyam

)

will be aware that

mudrā

s

are the very essence of that sacred art.

The Scriptures of several religions tell us that, over and above sa-

cred art—and prior to it—, God’s truth is manifested first and foremost