Among the Bohemians (5 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

Returning to the Bohemian artists of this period, we have to adjust our own expectations in order to understand what living on a low income meant in England in the first half of the twentieth century.

The middle classes already lived frugally enough; they had no modern-day superfluities.

Cutting loose from cramped conventional middle-class society and from regular sources of income didn’t mean renouncing luxuries, it meant renouncing necessities.

It meant going without regular meals, economising on heat and clothing, reducing one’s living to the essentials.

The fact is that by opting for a life independent of the rat race, many artists were forced to become déclassé, and this was a genuine sacrifice, albeit a willing one.

It took real courage to opt for the life of a ‘struggling artist’.

Remember too that for self-employed people before the Second World War there was no automatic benefit system, as there is today.

Skilled artisans or their widows might claim from the Friendly Benefit Societies; ex-employees could draw the dole in times of hardship, and low earners who had paid their compulsory contributions were also entitled to free medical treatment by the ‘panel’, otherwise the doctor expected prompt settlement.

The prospect for an unsalaried freelance artist who could not sell his or her work, or survive by other means, was starvation.

*

These realities give a context to the evidence gleaned from artists’ memoirs, letters and biographies of the period.

Turn-of-the-century London: the impoverished Arthur Ransome finds himself unable to earn, and is compelled for a week to live off apples and cheese which cost 2d a pound.

Slade student Edna Waugh stands her friend

Gwen John a boiled egg and coffee because she is too poor to buy herself a midday meal.

Jacob Epstein earns one shilling an hour as an artists’ model.

His trousers are torn, he cannot afford a haircut, and he sleeps under newspapers.

The early 1920s, and the aspiring artist Kathleen Hale’s luck has run out; she is only able to save herself from starvation by selling her hair.

Sophie Fedorovitch, an exiled Polish painter, is living in one room on the Embankment, with no bed, only a chair to sleep on, and a broken window pane which she cannot afford to have mended.

The newly married artists John and Christine Nash are struggling to feed themselves on the proceeds from John’s wood engravings.

If he makes three guineas Christine reckons they can eat for a month.

Constantine Fitzgibbon was convinced that by the 1930s conditions for artists had deteriorated yet further – ‘There was suddenly much less money about.’ The Depression meant that parents were even more unwilling to subsidise the younger generation in feckless activities like painting or writing poetry.

Compared with what he saw as the irresponsible freedom of art students in the 1890s, Fitzgibbon insisted that his contemporaries had no room for manoeuvre: ‘What the young men of the thirties could afford was a bedsitter and beer and sometimes Bertorelli’s.’

Bertorelli’s could do a half-portion of spaghetti in those days for fivepence, while a bedsit might cost about twelve shillings a week; (in Dylan Thomas’s case the rent was extracted from him by his flatmates who held him upside down and shook the shillings from his pockets).

Two pounds a week would keep the wolf from the door, just.

I don’t know what I lived on during this period

recalled the writer Philip O’Connor of that time…

… on sixpences, half-crowns… friends, my sister; I painted water-colours for our local art-dealer and junkman, who paid me 1½d each for them, and up to five shillings for oils… when [I was] very short, I would raid my sister’s flat, mostly for pots of jam.

But it all depended on what you expected of life, and a cheerful Micawber-like optimism can be discerned among some very poor artists who found to their joy that they could live within their income.

Augustus John’s wife, Ida, wrote to a friend describing the family’s life in Paris in 1905.

They had almost no furniture, only one bed between the three adults and five babies,

and bare boards on the floor.

But Ida was content: ‘I think we must be rich, because though there is such a lot of us, we live very comfortably and are out of debt.’

Such happy situations were rarely the result of financial competence.

Detached from their class, many artists abandoned hope of ever acquiring middle-class virtues like how to handle money.

The careful keeping of accounts, an activity so dear to the heart of the bourgeois chatelaine, was in any case dismissed in most artistic households as petty, materialistic and irrelevant to art.

The themes of unworldliness and poverty run throughout Arthur Ransome’s

Bohemia in London

(1907), an autobiographical account of a youthful sub-culture.

This engaging book is a companion guide for the novice traveller in Bohemia, with lively descriptions of the terrain, the natives and their habits, diet, language and customs, by a resident; it was written when Ransome was only twenty-two, twenty-five yean before he wrote the first of his classic children’s books,

Swallows and Amazons

(1930).

An odd, subjective ramble, its very naiveté is persuasive.

For Ransome, you could only qualify as a Bohemian by being poor, but in Bohemia, discomfort was immaterial, and hunger insignificant compared to the bliss of living there.

His descriptions of his garret existence in Chelsea – the Bohemian heartland in those days – are full of nostalgia for a penurious but happy existence.

‘Those were wonderful days in that winter of 1904,’ he later wrote in his autobiography, and in the next sentence: ‘I never starved but I was always hungry.’

In the following decades, Arthur Ransome’s Bohemia was unconsciously replicated by a generation of hard-up artists in the basements and studios of Chelsea, Fitzrovia, Camden Town and Bloomsbury.

Their priorities, like his, were not financial:

The men who really care for their art, who wish above all things to do the best that is in them, do not take the way of the world and the regular salaries of the newspaper offices.

They stay outside, reading, writing, painting for themselves, and snatching such golden crumbs as fall within their reach from the tables of publishers, editors and picture-buyers.

They make a living as it were by accident.

It is a hard life and a risky…

Literature was Ransome’s passion.

Rather than lose the chance of buying two leather-bound volumes of

The Anatomy of Melancholy

for seven-and-sixpence, he preferred to go without dinner and walk home to Chelsea.

One can’t help sympathising with this kind of spontaneous improvidence, uncalculating and naive as it is, just as it’s hard to resist, against one’s better judgement, applauding Augustus John for crazily investing

£

300 in the construction of primitive aeroplanes by a French crank called Bazin.

There is no evidence that anything became airborne as a result.

John’s friend and rival Jacob Epstein – who never learnt how to sign a cheque – used to arrive at his mistress Kathleen Garman’s house once a week laden with apricots in brandy, exotic flowers and fruit.

‘I wish he could have given us something for the housekeeping,’ recalled Kathleen’s daughter sadly.

The actress Brenda Dean Paul and her mother never failed to deck their studio with gardenias and tuberoses, even when all they could afford to eat was a boiled egg.

Such grand gestures would furnish further proof to the bourgeoisie of artistic foolhardiness.

*

‘Not taking the way of the world’ often meant serious hardship; clearly Bohemia’s poor had to find other sources of income than painting, poetry and prose.

All too often, they were dealing in unsaleable commodities.

Luckily, their powers of invention were not wasted in coming up with ideas for keeping themselves afloat.

A well-disposed dentist appears to have accepted paintings in return for dentures in St Ives.

Nina Hamnett kept herself in drinks outside pub hours by painting murals on the walls of the Jubilee Club.

*

Lilian Bomberg started a greengrocer’s shop which foundered through lack of custom: the strait-laced locals were deterred by the sight of Bomberg’s Bohemian garb as he perched on a ladder painting the sign to hang above it.

And the poet Liam O’Flaherty took up catering:

[We’re] setting up ‘tea-rooms’ in this house, giving teas to tourists.

Crowds of people come up to see the mountains in summer, so they will probably make the thing pay.

Margaret will cook, Adelaide will serve, and I will be on the premises armed with a monstrous axe to club the bourgeoisie if they become impertinent or fail to pay their bills.

I hope we make some money in the business because it seems there is very little hope of making money any other way.

And in a lucid moment between drugs, apache lovers and absinthe, Epstein’s luscious model Betty May decided to start a sweetshop in the country, making all the confectionery herself.

Rather to her surprise it was a success, but she was forced to give it up by her current husband and his disapproving

family who thought ‘Miss Betty’ should not be engaging in retail trade.

Mortified, she was on the next train back to the Café Royal.

There was always a familiar face there who would stand her a drink.

The Café Royal was a good place for a spot of wheeler-dealing too.

When times were hard Betty or her fellow Bohemians might make the price of a glass of absinthe by supplying gossip or copy for an exhibition critique to the Fleet Street hacks who flocked around its tacky but opulent interior hoping for morsels from the art world.

If this failed they could always borrow from a friend.

*

Bohemia’s position on borrowing money was startlingly distinct from that of conventional society, and it still is.

Most people in the early twentieth century subsisted on cash; bank accounts were only for the better-off.

Lady Troubridge, author

of The Book of Etiquette

(1931), categorised ‘borrowing[ing] even the smallest sum of money’ alongside unpunctuality, putting one’s feet on the chairs or sneezing in public.

This was, indisputably, ‘Conduct which is incorrect.’ To offend against Polonius’s famous injunction ‘Neither a borrower nor a lender be’ had been regarded for centuries as taking the slippery slope to perdition.

The easy-come easy-go, sometime-never attitude to borrowing which existed in Bohemia was worlds away from the condemnatory stand of Lady Troubridge and her ilk, and yet the anecdotal evidence is that hardly anyone was hurt by it.

This was because in Bohemia you didn’t borrow ten pounds to last you the month, you borrowed your twopenny bus fare home.

You hung around Augustus John till he stood you a drink.

On the whole the borrower was straight: ‘I am asking you to send me fifty pounds,’ wrote the South African poet Roy Campbell to a friend, C.

J.

Sibbett.

He was in dire need.

‘I shall never be able to repay it.

I am asking it as a gift.’ Sibbett sent twenty-five pounds straight away, and another twenty-five soon after.

No doubt there were scroungers and spongers, but it was a two-way process, and the Bohemian community took a different attitude to helping out needy comrades.

Viva King, for example:

[My mother] thought [Francis Macnamara] a sponger…

she wrote in her piquant autobiography,

The Weeping and the Laughter

(1976), recalling her curious platonic relationship with one of Augustus John’s closest friends:

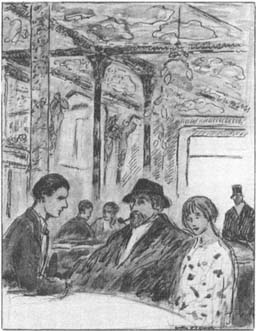

‘If you want to see English people at their most

English, go to the Café Royal where they are

trying their hardest to be French,’ wrote Beer-

bohm Tree.

Augustus John was the Café’s

acknowledged king.

Perhaps because I have always been a rock for spongers to cling to, I have never understood why scorn is heaped upon those who are often clever enough to take with grace what is usually freely given.

Viva, a Bohemian celebrity in her own right (though never an artist) had experienced poverty but married wealth; her sympathies, however, remained with the poor and she strongly appreciated Francis Macnamara’s Irish gaiety and wit.

Viva generously forgave his sponging habits in return for the pleasure they had together – trips to the zoo and strolls round antique shops in the Brompton Road – while taking the view that artists are exempt from the rules; you lent money to them out of the goodness of your heart, understanding and forgiving them whether they were geniuses or not.

Above all, there was a tacit understanding that you didn’t expect to be repaid.

For Francis Macnamara the word ‘lender’ was synonymous with ‘giver’, and his children were brought up with this assumption.

His daughter Nicolette grew up between her own family and the Johns (Augustus was a second father to her).

It was they who influenced her belief that money represented only one thing – freedom of action – while entailing no

responsibilities.

Neither she nor anyone she knew had ever ‘earned’ money.

Francis wrote; Augustus painted.

This they did from innate talent.

‘Money was a secondary consideration.’ When needed it would appear as if by magic from some patron or rich relation.

Failing this, borrowing was the obvious solution.

When Nicolette married the painter Anthony Devas she discovered to her astonishment that his family did not see things in the same light – ‘With the Devases, borrowing was to be avoided except in an emergency.’ It took Nicolette much painful adjustment to come to terms with the conventional Devas approach to money, where borrowing and not returning money was seen as bordering on theft.