Among the Bohemians (4 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

Poverty in England could be even worse.

A visiting nineteenth-century Frenchman, Francis Wey, recorded with horror the condition of the truly destitute in London, who, little better than gutter-dwellers, lay ‘higgledy-piggledy in the mud, hollow eyed and purple cheeked, their ragged clothing plastered with muck’.

Actual starvation was not unknown, and in 1900 a fifth of the population of this country ended their days in the workhouse.

Even in 1937 George Orwell was to write angrily of the vile and undignified squalor, the subsistence diet and the infested dwellings of the working classes in Wigan and elsewhere.

This then was the prospect in life for anyone who had no means of support.

The message was there for anyone to read – forsake money at your peril.

Thus, to the outside world, artists seemed set on an unthinkable course towards self-destruction.

In his thinly disguised autobiographical novel

Of Human Bondage

(1915) W.

Somerset Maugham dramatises the experience of making that leap.

After an alienated childhood, his young hero Philip Carey reaches a point where he feels he can only find self-expression as an artist.

Like so many others, Philip had fallen under the spell of Murger’s

Vie de Bohème.

‘His soul danced with joy at that picture of starvation which is so good-humoured… squalor which is so picturesque…’ With little money, and to the appalled disapproval of his stern uncle – a vicar for whom painting is a disreputable and immoral activity – Philip decides to risk a spell in Paris as an art student.

Turn-of-the-century Paris, with its studios, cafés and general Bohemian élan, served for the majority of English artists of that period as an indispensable rite of passage on their route to artistic maturity.

Once enrolled in art school, Philip sets out to experience Bohemian Paris to the full.

Early on, he meets a dejected young woman who, like him, has come to the city to seek her artistic fortune.

Fanny battens on Philip.

She is unattractive, untalented, ungracious; she possesses a single hideous and tattered brown garment.

At a brasserie together one evening Philip is disgusted by Fanny’s repellent table manners – she eats like an animal.

Nevertheless their relationship progresses falteringly, as much from Philip’s embarrassed pity for Fanny as because she seems to have no other friends.

Then for a while they lose touch.

One day Philip receives a message to come to Fanny’s garret studio; he makes his way up to the tiny attic, and there finds her body, emaciated, hanging from a nail in the ceiling.

She has been dead for some days.

Horrified, he pieces together the story:

She had been oppressed by dire poverty.

He remembered the luncheon they had eaten together when first he came to Paris and the ghoulish appetite which had disgusted him: he realised now that she ate in that manner because she was ravenous… She had never given anyone to understand that she was poorer than the rest, but it was clear that her money had been coming to an end, and at last she could not afford to come any more to the studio… She had died of starvation.

Did the prototype Philip Carey have this experience?

It is hard to tell; biographies of Somerset Maugham do not shed light on this episode in his novel, with one possible exception.

On 27 July 1904 Willie Maugham’s brother Harry, an aspiring writer and Bohemian, was found lying on his bed, fully dressed, writhing in agony: he had swallowed nitric acid, and had been there for three days while the corrosive chemical gradually killed him.

Harry Maugham’s dreadful death, reminiscent of Chatterton’s, is echoed in the novel – the despair of the embittered artist whose hopes will never be realised, the impoverished Bohemian who can see no future in his art, yet no reason for existence in any other of life’s paths.

For as Philip Carey now discovered, poverty was not romantic.

Again and again in the annals of Bohemia the pain of penury is expressed with

anguish and bitterness.

‘The poverty among my contemporaries was terrible’ recalled the painter C.

R.

W.

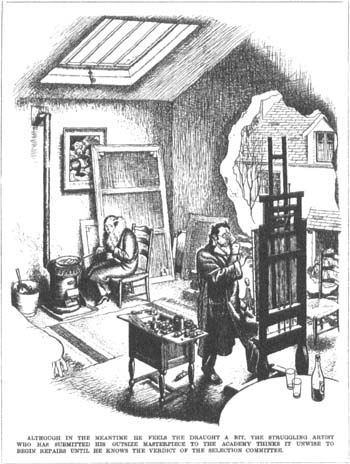

Nevinson of his pre-First World War student days, and this is borne out by countless examples of artists reduced to the bare necessities – sleeping under newspapers for warmth, freezing in chilly studios with broken windows, eating packet soup day after day or subsisting on crusts and tea, walking to save twopenny fares, owing rent.

Punch

, 13 April 1932.

With such tangible examples of the results of trying to live from art, it was not surprising that the majority of the bien-pensant middle classes took a dim view of art as a profession, seeing Bohemian poverty as at best self-indulgent folly, at worst criminal recklessness.

The disgust felt by Philip Carey’s uncle at his nephew’s indigence betrays a profound defensiveness and self-righteous indignation.

For the likes of the Rev.

Carey, his nephew’s rejection of the conventional, salaried world represented much more than just light-hearted unworldliness.

This was an affront to his entire way of life.

For by the beginning of the twentieth century society had become an unwieldy but also extremely expensive edifice to maintain.

High society

under Edward VII was a tottering display of extravagant magnificence – huge meals, huge houses, huge balls.

Lower down the scale the middle classes went as far as they could in emulating their betters.

Social presentation was considered vitally important; the bourgeoisie was not prepared to stint on housemaids and laundered tray-cloths, embossed calling-cards and kid gloves.

The conventionally minded felt snubbed, indeed shocked to the core, by those who turned their backs on money.

It was not nice, it was not respectable, it was dangerously improvident.

The result for many young artists was a head-on collision of values with the older generation.

For the young, opting for painting and poetry meant salvation.

For the old, such a choice was equivalent to cheating on the Stock Exchange or some such almost unmentionable behaviour.

There was no money to be made out of poetry.

The poet Stephen Spender’s relatives saw his choice of career as ‘perverse, obscene, blasphemous… depraved…’ But the tenacious ones held on to their vocation, for rejection of the conventional moneyed world was what gave them their very identity.

Bohemians felt that they were inheritors of a kingdom where the rich man cannot penetrate.

Being penniless qualified one for a higher form of life than that offered by Victorian society.

It is arguable that the very label Bohemian, with its romantic echoes of far-off lands, was adopted to give status to the poor who might otherwise have sunk without trace into the gutter.

And the direr their Bohemian distress, the more it sanctified the conviction that art was worth making sacrifices for.

Contempt for money was the extension of this position.

If poverty is an imperative for an artist – as many believed it to be – then wealth was to be derided, regarded as sordid and corrupting to the integrity of the artist.

Bohemia on the whole felt a psychic distaste for Mammon.

Of course that attitude was in no way exclusive to Bohemia; it has a long Christian tradition, and by the end of the nineteenth century writers like Dickens had done much to elevate the status of the poor while condemning the cruelty and avarice pf the Gradgrinds of this world.

Many thoughtful and high-minded people were also struggling to come to terms with their instinctive aversion to the materialism and excess of the Victorian and Edwardian age – like the founding fathers of Fabianism and socialism whose tenets of redistribution led to the formation of the Labour Party.

But this particular Bohemian attitude was an extreme position.

Under the pseudonym George Beaton the writer Gerald Brenan published

Jack Robinson: A Picaresque Novel

in 1933.

In it, he wrestles with the question of whether one can renounce material things, and exist ‘like the lilies of the field’, trusting to fortune and inspiration.

As a young man Brenan – who

came from a well-to-do upper-class family – was intensely attracted by the idea of poverty:

The life of the poor, I held, had necessarily a greater reality than that of the rich because it was more exposed to fate and chance.

It had also a greater blessedness if it was accepted voluntarily.

Like his hero – with whom he manifestly identifies – Brenan himself had run away from home in his teens and taken to the road as a tramp, travelling a pilgrim’s path to self-discovery.

In the novel Jack encounters a succession of colourful characters who flesh out his theories and influence his progress.

One of these is the vagabond Irish philosopher Kelly whom he runs into singing his way down a hillside track:

‘You see myself,’ he went on.

‘Would you call me a rich or successful man?

I don’t mind – speak plainly.’

I looked at the stained clothes drawn round his little body, at the long patched boots and haggard face, and answered:

‘No, I can’t say I should.’

‘Now that is because you judge by material judgements.

Seen in the spirit I am happy and successful, brilliant and free and want for nothing… I sing without ceasing from morning till night.

Didn’t you hear me?’

‘Yes, I did.’

‘Do the rich sing?

No.

Do they live in the open air under the beautiful trees?

No, they do not.

Do they love Nature?

Do they delight in poetry?

Not one.

Oh, I pity the rich, I pity all men and women who are rich with all my heart.’

Thus Brenan/Beaton expresses the quintessential Bohemian attitude to money, though Jack Robinson’s subsequent progress does much to dispel this outlook on life.

But many Bohemians eagerly espoused it, and found in it a sense of validity and incorruptibility that nothing could take away.

Believing that money was sordid and vile, that it cut you off from the raw material of life so essential to the artist, that it was repellent to place filthy lucre in proximity to art, did much to take the sting out of hunger and cold.

Dylan Thomas and his wife, Caitlin, took the attitude to its logical extension and vaunted their poverty as an indispensable ingredient in their art.

Thomas’s biographer and close friend, Constantine Fitzgibbon, who joined him on many a pub crawl, described Dylan’s attitude best:

Just as at school he had to be thirty-third in trigonometry, just as in America he had to be the drunkest man in the world, so in London in 1937 he could not simply be a poor poet: he had to be the most penniless of them all, ever.

Therefore such money as he might make or be given had to be spent, given away, even lost immediately.

Money had become only another skin to be removed as quickly as possible in his revelation of the absolute Dylan.

Like so many, perhaps like all, his attitudes, this one never really changed.

It was one of the causes of his ruin.

Caitlin found herself almost dazzled by ‘the romance of poverty… the inspiring squalor of the artistic world’ in which the two of them lived.

Yet after his death she bitterly recalled how Dylan’s renunciation of money entailed an enthusiastic advocacy of the Chatterton model: ‘Poverty and, preferably for the perfectionist, an early agonising death thrown in too.

Dylan scrupulously fulfilled both these romantic conditions.’

Bohemians like Dylan and Caitlin Thomas were proud to place art before bourgeois comforts; managing to stay alive on very little money was cause for self-congratulation.

No-frills self-sufficiency seemed a laudable and entirely achievable aim; and who needs parlourmaids and table-napkins anyway?

Yet it can be hard to appreciate that, for a large proportion of the middle classes, keeping up to the mark was already a struggle, and to opt out of that world was to descend from what was de facto a low level of provision and comfort.

The parlourmaids and calling-cards were paid for out of tight incomes, nor did families like Ursula Bloom’s have any of the expectations that we have today.

The daughter of a country clergyman, she gives us a picture of her family’s life both before and after the First World War.

They lived an impeccably respectable life in a country vicarage on three hundred pounds a year: ‘Few people realise today how careful the whole of England was about the spending of money, and all families saved a little for the rainy day…’ remembered Ursula.

Servants’ wages had to come out of the budget, because the middle classes took a certain retinue of staff for granted, but the family made economies on every front.

They never bought expensive joints; clothes and furniture had to last; rooms were rarely redecorated, and nobody bought manufactured toilet paper because it was too expensive.

Socks were always darned; middle-class formalities like the tipping of servants could leave one disastrously short of cash.

With careful penny-pinching, nobody went hungry, but no housewife worth her salt omitted to keep scrupulous accounts, or to pay the butcher’s bill on the nail.

What is striking about such examples as the Blooms is that one would expect such families to have more spending power today.

Undoubtedly at

the beginning of the twenty-first century we are accustomed to spending a far higher proportion of our available income on what would, just fifty years ago, have been seen as impossible luxuries.

Today a country vicar would automatically expect to own a car, a refrigerator and a telephone, to travel and have holidays, to purchase ready-made clothes at regular intervals, eat convenience foods and occasionally eat out, buy cheap medicines and afford a television and radio.

Not one of these things was generally affordable by the Blooms, never mind taken for granted.

Before 1945 this was the general state of affairs.

The only thing that our generation no longer expects, which our grandparents counted upon, was servants.

At the beginning of the twentieth century the labour market was such that every middle-class household could afford servants, and it was not until the Second World War that even people on moderate incomes found it hard to afford the minimum of one maid and a charwoman.