Amazing Tales for Making Men Out of Boys (20 page)

Read Amazing Tales for Making Men Out of Boys Online

Authors: Neil Oliver

Sir Ernest Shackleton and the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The interior of South Georgia was unknown to man in 1916. Captain James Cook had made the first landing on the shore of the island, in 1775, and named the place for King George III. Hunters came soon after, attracted by reports of abundant wildlife, and all but wiped out the population of seals that struggled on to the rocky beaches each year to give birth to their young. By the turn of the 20th century it had attracted whalers from Norway, who made working stations for themselves in the natural harbor they called Grytviken. There they could process their catch before making the long journey home to the other end of the world.

The coastline of South Georgia had become familiar to mariners of the most adventurous sort—notably those like Scott and his men making for Antarctica—but in more than 135 years no one had found the need or the nerve to venture among the mountains and glaciers that loomed behind the shoreline.

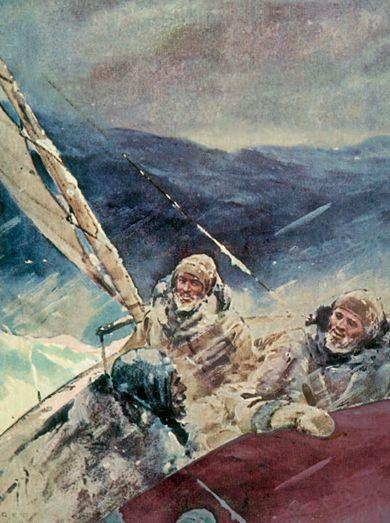

In the early hours of May 19, 1916, three men set out from King Haakon Bay on the southwest of the island, making for a whaling station at Stromness, on the northeast coast. As the crow flies, it’s a distance of no more than 40 miles, but it was across completely uncharted territory. Who knew what lay ahead of them? And this was to be no sightseeing trip—this was a matter of life and death. Depending upon the success of the crossing were the three men actually embarking upon the journey, three men left behind in a cave at Haakon Bay—and 22 men stranded beneath two upturned boats on a barren, un inhabited rock called Elephant Island, 800 miles away across the Southern Ocean.

They could hardly have been less well equipped for the ordeal ahead, these pioneers. Already physically and mentally exhausted by months of hardship

in the toughest environments on earth, half-starved and frostbitten, they set out wearing worn-out clothes and carrying their food rations in a sock. They had scavenged brass screws from the timbers of the boat that had brought them to the island, and worked them into the soles of their boots in hope of adding a bit of grip, the better to tackle glaciers, cliffs and ice-covered rocks. They carried a primus stove, fuel to cook six meals, 50 feet of rope and a carpenter’s adze.

Three men set out that morning, tramping into the frozen dark with the weight of the world on their shoulders. Their names were Tom Crean, Frank Worsley and Ernest Shackleton—and they were on the last leg of one of the greatest adventures of all time. But as the hours and miles began to fall behind them, each had the strangest and most unexpected feeling. None of them mentioned it at the time—there was too much at stake and no strength left for fanciful talk—but each felt it just the same. As they walked across that barren and treacherous landscape, all three felt the unmistakable, unseen presence of a fourth soul.

Ernest Shackleton was born in County Kildare, in Ireland, on February 15, 1874. The family later moved to London, where Ernest was educated. His father was a doctor—and wanted his son to follow him into the profession—but Ernest was a stubbornly independent boy and joined the Merchant Navy instead, winning his master mariner’s ticket in 1898.

A member of Scott’s ultimately triumphant

Discovery

expedition of 1901–4, he was humiliated by his leader’s decision to send him home early after his near-death during the “furthest south” march of 1902–3. Taking his dismissal from the team as a personal slight, he developed a grudge for his erstwhile boss that never left him. The characters and personalities of the two men were too different, and their ambitions too much the same, for there to be any hope of repairing the damage. Alpha dogs lead alone.

In April 1904 he married Emily Dorman, a friend of his sister’s,

and the couple would eventually have three children together. Like all men of his calling, the ties of family were never enough to keep him at home. Siring children was one thing, but the job of rearing them and loving them was among the many things those adventurers freely chose to leave behind them in their wake.

Shackleton’s adventures on the southern continent continued without Scott, and in March 1909 newspapers carried reports that he had made it to within 100 miles of the Pole during his

Nimrod

expedition. It was another tale of awful hardship, and the readers could only wonder at the spirit and determination of such men. Shackleton and his three comrades had barely made it back to their base alive, but on his return to Britain he was awarded a knighthood. It was the best shot at the Pole until Scott and Amundsen would make their respective trips to the place in 1912.

By 1913 Shackleton had conceived of what he called the “last great journey on earth.” Both Poles had been conquered and now it required imagination to come up with anything else worth doing at the ends of the earth. Shackleton was nothing if not inventive, and came up with a splendid adventure he called “The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.” He was going to lead a handpicked party of men from one side of the southern continent to the other, via the South Pole. As if that wasn’t bold enough, he said they would cover the distance of 1,800 miles in just 100 days. He had little experience of, far less expertise in, the use of sled dogs and yet he planned to take 120 of them to spare his men the old horror of man-hauling the sledge-loads of necessary food and kit across the barren terrain. No one had ever contemplated such an undertaking before, but while Scott had been every inch the reticent Navy man, less than comfortable when exposed to the full glare of publicity, Shackleton had something of the flamboyant showman about him.

When it came to raising funds for the trip, he took to the job like a natural. He needed the modern-day equivalent of around

$4.5 million to finance the project, and cheerfully embarked upon the necessary round of glad-handing and public speaking. David Lloyd George, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, provided a fifth of the total from the public purse. The rest was harvested in the form of donations great and small from the people of Great Britain. The largest single gift—something in the region of $1.5 million in today’s money—was received from James Caird, a multi-millionaire jute manufacturer turned philanthropist, from the Scottish city of Dundee.

The expedition headquarters were established at an address in Burlington Street in central London, and legend has it that an advertisement was placed in the newspapers that read:

Men wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success.

Not exactly an invitation to join the Big Brother house then, but it attracted the usual mix of the good, the bad and the ugly. Thousands of men offered their services and Shackleton famously sorted the letters of application into three boxes marked, “Mad,” “Hopeless” and “Possible.” Gradually he whittled them down, using his considerable ability to judge the character of men almost at first sight. Three women applied as well, but Shackleton decided the expedition would be challenging enough without the complication of adding a second sex into the mix.

The expedition would take two ships. The main thrust of the voyage would be undertaken by the

Endurance

, a converted Norwegian-built vessel that had already won its colors in the Southern Ocean. She would carry Shackleton and his team to the Weddell Sea, from where they would head off toward the Pole and the eastern coast of the continent beyond. A second ship, the

Aurora

, would sail to Cape Evans in McMurdo Sound in the Ross

Sea, and drop off a team of men tasked with traveling into the interior from the other side of the continent. They would then work their way back toward their ship, dropping supply dumps as they went. Shackleton and his men would collect these supplies and make use of them as they completed the second half of their proposed journey from the Pole back out to the sea.

By June the

Endurance

was in London, being loaded with the mountains of supplies required for such a trip. On the 28th of the month Archduke Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian throne, was assassinated in the Balkan city of Sarajevo and the kindling of the Great War was lit. On August 1, the same day that Germany declared war on Russia, the

Endurance

set sail from Millwall Docks. Shackleton brought the men together on deck and said any and all of them were free to leave the ship and enlist in His Majesty’s armed forces, if they so wished. The ship docked in Margate and several members of the team duly took their leave of it, and headed off to war. Shackleton sent a telegraph to the Admiralty saying that he, his ship and all of its supplies were at the disposal of the country. But Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, sent back a one-word reply urging the men to go ahead with their odyssey. It read: “Proceed.”

Taking the message to mean that the continuation of the expedition was now a patriotic duty, Shackleton pressed ahead with his final preparations. He stayed behind in England to secure the outstanding funds pledged for the trip and sent the ship and her crew on to South America, where she made port in Buenos Aires, in Argentina. He finally sailed from Liverpool and rejoined the

Endurance

in mid-October. On the way to South Georgia, their last staging post, they discovered a stowaway—a 19-year-old named Percy Blackborrow. Shackleton gave the teenager a severe dressing down, but decided he should be allowed to join the team. Now there were 28 men en route to Antarctica.

On arrival in Grytviken, Shackleton received depressing news

from Thoralf Sorlle, one of the leaders of a party of Norwegian whalers working there. He said the pack-ice was further north than usual for the time of year, and in the opinion of him and his men it would be foolish to take a ship toward the Weddell Sea in such conditions. Despite the warnings—and advice to delay the trip south—Shackleton would not be put off. On December 5, 1914, while the great nations of Europe set about tearing themselves into bloody pieces, the

Endurance

sailed away from the world of men.

Sure enough, they encountered pack-ice almost at once and by Christmas 1914 they were making no more than a mile an hour on a typical day. At the other end of the world, Allied and German soldiers were putting down their weapons and walking tentatively into no man’s land to wish one another a Merry Christmas. It was the last time they would extend such a courtesy to their fellow men. They made time to perform proper funerals for their dead and men from both sides came together, beside at least one grave, to recite, in their own tongues, verses of the 23rd Psalm. What would the men of the

Endurance,

so very far away, have felt if they could have heard the words?

The Lord is my shepherd. I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures. He leadeth me beside the still waters. He restoreth my soul…Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil…

Men in danger have a tendency to look beyond what they can see all around them, to reach out for an unseen hand. Those men aboard the

Endurance

were from Edwardian Britain—and relied upon their Christian faith to an extent that is hard for many people living today to imagine, far less empathize with. There is no denying that their belief in a merciful God was a comfort to them.

On January 19, 1915, the men awoke to find they were no longer

aboard a ship at sea, but in a no man’s land of their own. During the night the pack-ice had completely closed around them; still waters indeed. Despite Herculean efforts in the days and weeks that followed—attacking the ice with picks and saws in an attempt to cut a channel toward open water—they finally had to accept they were stuck fast, prisoners of the floe. There was nothing for it but to wait out the Antarctic winter aboard their stranded vessel.

While the men settled into the routine of monotonous days lived out in darkness, Shackleton remained optimistic. This was only a delay, he told himself and anyone who would listen. The ice floe of which they were now a fixed part was drifting slowly northwards with the currents and prevailing winds. Eventually they would be so far north they would be released from their prison and able to make the journey back to South Georgia. Then, when conditions were right a few months later, they would return to Antarctica and make their crossing of the continent as planned.

Nature had other ideas, however. Deeper into the southern winter, the weather steadily deteriorated, with temperatures dipping to minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit. Gale-force winds drove the ice, twisting and tormenting it so that the separate floes ground and squealed against one another, making all manner of unearthly sounds. Aboard the

Endurance

the men could only listen while massive forces were brought to bear upon her timbers. The ice screamed and growled and in her agony the ship screamed back.