Amanda Adams (13 page)

Authors: Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists,Their Search for Adventure

Tags: #BIO022000

Still, Florence did some interesting and daring work herself. She interviewed destitute families and documented their experiences, using a kind of ethnographic approach to glean insights into hardships faced by England’s poor. From this work came a massive book called

At the Works: A Study of a Manufacturing

Town.

The conclusions she drew did little to remedy the situation or the cause of the problem—gut-wrenching poverty and a brutal class system—but the plight of lower-class families was described in sympathetic detail. By her work, she helped bridge understanding between one class and another and, more than anything else, stirred up some empathy. When her stepdaughter later crossed deserts and befriended the people that lived therein, she would employ a similar approach: sitting down with strangers to listen and learn.

As a young girl, Bell was powerfully smart. Feisty, hotly opinionated, boastful, and confident, Bell was always in pursuit of a verbal wrangling and a chance to broaden her own thinking. She devoured books. She demanded attention from the housemaids, loved to argue her point of view, and wanted to learn what people knew but was less inclined to feign interest in what they thought. Her interest in the common girlish lessons of sewing, music, and singing was minimal at best, but she was wickedly skilled at a riding a pony. She played sports, tortured her brother with dares, and threw her dog in the lake just . . . because.

Her governesses and teachers were exasperated by Bell and astonished by her quick mind and aptitude for learning. As her intelligence became increasingly apparent, the teenage Bell became more and more impervious to the monotony of her at-home schooling and restless with the insatiable drive that eventually came to define her. She was also argumentative and bossy, and her parents recognized that the normal sequence of events for a girl Bell’s age—the formal introduction to society, a time to court and spark, a wedding and children soon after—wasn’t going to fly. When she was fifteen they made the exceptional decision to send her to Queen’s College, an all-girls’ school in London. From there, Bell’s razor-sharp intellect and her professors’ persuasive recommendations that she continue her education allowed her to carry on her studies at Oxford in 1886. Once enrolled, she started attending the Oxford Archaeological Society meetings.

Bell was at Lady Margaret Hall, one of the two women’s colleges at Oxford, and while living on campus she was, as one of her biographers put it, “something of a social hand grenade.”

8

No doubt she was frustrated by the restrictions placed on her because she was a woman: always required to have a chaperone to go anywhere, treated as an unwanted interloper in an almost exclusively male environment, often made to sit at the back of the room and told to hush. But she aired her thoughts freely and without a second’s hesitation and even told off her male teachers when she felt they deserved it. To her female counterparts, she was a hero. Her friend and fellow student Janet Hogwarth would later write in memory: “Gertrude Lowthian Bell, the most brilliant student we ever had at Lady Margaret Hall . . .—alive at every point, the vivid, rather untidy, auburn-haired girl of seventeen . . . took our hearts by storm with her brilliant talk and her youthful confidence in her self and her belongings.”

9

By the time Bell completed her studies at Oxford, in a remarkable two years instead of the normal three, she was the only woman to have ever taken a First in Modern History. This was (and remains) the greatest academic achievement that could be awarded a student, male or female. Although her degree was never formally awarded—Oxford did not extend hard-earned degrees to female students until 1920—Bell’s own glee about her monumental accomplishment shines in a quick letter to her stepmother. Dated 1889 in London, it read: “Minnie Hope was sitting with an Oxford man. Presently he grabbed her hand and said ‘do you see that young lady in a blue jacket?’ ‘yes’ said Minnie lying low. ‘Well,’ said he in an awestruck voice, ‘she took a first in history!!’”

10

She did, and soon afterward she was off to begin a series of journeys across uncharted, archaeologically rich lands that would eventually make her a significant figure

in

history herself.

THE EXTENSIVE TRAVELS

that Bell would embark upon were possible not only because she had gumption but also because her family had money and influence. Florence’s relations and friends abroad allowed Bell to start a traveling career as the doors of all the French and British embassies were flung open wide in welcome.

It was in

1892

, at the age of twenty-four, that she got her first taste of the Middle East. Persia, the place she had “always longed to see,” was to be hers for six months. Florence’s sister Mary and her husband, British Ambassador Frank Lascelles, had invited Bell to join them on a tour. In preparation, Bell tackled Farsi and achieved basic fluency. Mastering multiple languages became a trait of hers. She spoke French, German, Persian, Arabic, and enough Hindustani and Japanese to get by. Although she had an exceptional talent for learning languages, she still struggled when she started. Practicing Arabic, she complained to her father in a letter: “I thought I should never be able to put two words together . . . there are at least three sounds almost impossible to the European throat. The worst I think is a very much aspirated H. I can only say it by holding down my tongue with one finger, but then you can’t carry on a conversation with your finger down your throat can you?”

11

In Persia, Bell stayed in Teheran, where she fell in love with scenes of stone and sand. The desert’s vastness thrilled her; she thought its miles of nothingness were wonderful. She must have seen something of herself in its stretch, aware that the desert was uniquely suited to absorb her boundless energy. She continued to travel around the world with her father or her brother Maurice for the next seven years, and it wasn’t until

1899

that she returned to the Middle East. Then she began to hear the siren’s song of archaeology and made it her lifelong passion.

BELL’S WORK AS

an archaeologist was more dangerous and more bug-ridden, unmapped, and exposed to harsh conditions and hazards than that conducted by any other woman before World War

I

—and, safe to say, by most men too.

12

She normally traveled on horseback, occasionally by camel, and always alone except for the men she hired. It was often so scorching hot in the deserts that she wore full-length coats to ward off the white sun’s rays: “The sun was so hot it burnt one through one’s boots. I have gone into linen and khaki. The latter consists of a man’s ready-made coat, so big that there is room in it for every wind that blows, and most comfy; great deep pockets. The shopkeeper was very anxious that I should buy the trousers too but I haven’t come to that yet.”

13

Unlike Jane Dieulafoy, Bell never wore pants. She refused. Although she was sometimes mistaken for a man or boy, greeted as

Effendim!

(my lord) by desert Druze and Bedouin men, once she spoke, unwrapped the veils from her face, and took off her coat, there was nothing manly about her.

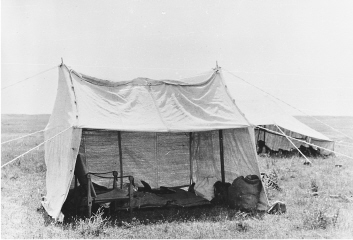

ABOVE :

One of Gertrude Bell’s field tents

Bell was a fashionista. Her wardrobe was all dressing gowns, velvet wraps, feathered felt hats, and crêpe de chine blouses. Her travel bags held porcelain china to dine on and crystal, delicate as her own English features, to drink from. Bell understood her power as a European woman abroad, and she never apologized for being a lady. She basked in her own sense of rarity and strode through even the most extreme field conditions in a skirt.

But she was practical too. In her post-Oxford, pre-archaeologist days Bell passed the time with a little mountaineering (she was a real hobby conqueror). She scaled icy ridges and high peaks in the Swiss Alps numerous times, had a particularly ferocious mountain named after her thanks to the glory of her ascent of it, and went down in the pages of climbing history as the unparalleled “prominent lady mountaineer” of her time, one who was venerated by the following praise: “of all the amateurs, men or women . . . [there were] very few to surpass her in technical skill and none to equal her in coolness, bravery and judgment.”

14

In her coolness, she took off her cumbersome skirts while climbing and made her way up rocky overhangs in only her undergarments. Clothing, though adored by Bell, could be left behind as easily as pretense and convention when circumstances required.

But there’s no doubt she loved her pretty things. She always perused the Harrod’s catalog to keep up with trends, and as a young woman in

1899

she would write to her sister Elsa, “My new clothes are very dreamy. You will scream with delight when you see me in them!” Much later, as a woman of fifty, masterminding and maneuvering in high political circles, she would still write her stepmother to ask for the latest styles in fashion—for a silk evening dress to be shipped her way by post, for “a green silk woven jacket thing with silver buttons,” please. She used both her elegance and the polished manners she inherited from her stepmother to advantage.

Pearls and feathers aside, Bell was still resilient in an unfriendly field. Despite the luxuries she grew up with, she could happily forsake lamb suppers, cream scones, and tea for big bowls of milk, sour bread, and

dibbis

(a sweet date syrup) and, on special occasions, sheep. She didn’t flinch from drinking muddy water—only declining a sip from cisterns that were “full of little red animals swimming cheerfully about.” Most mornings she breakfasted on “dates, camels’ milk and the bitter black coffee of the Arabs—a peerless drink.” For a treat there was white coffee: hot water, sweetened and flavored with almonds. On some hard nights when starry darkness settled in on what Bell called “starvation camp”: only rice and bread to nibble and no charcoal for fire or barley for the horses.

15

Outfitted in her long coat, she would withstand days of travel, some ten or more hours long, after which she would feel “as if I had been sitting in my saddle for a lifetime and my horse felt so too.” Her face was whipped by blowing sand, rain, sun, snow, and ice and sometimes clouded in warm, eerie mists that made the landscape around her disappear. The terrain ranged from sloping dunes to a crumbling rock that made the horses slip and skid, to yellow mud the “consistency of butter”

16

that threatened to swallow her team whole, pet dog included.

Come bedtime she endured a variety of makeshift camps. Some were pleasantly tucked into flowered hillsides, quaint villages close, running streams nearby; others were thick with black beetles or rocky affairs where a mattress was mere thistles and her bed fellows stinging flies. Most of her experiences seem to have kept her in high spirits, though, and were preferable to some stifling social event with English ladies. As she put it, “This sort of life grows upon one. The tedious things become less tedious and the amusing more amusing . . .”

Bell received an allowance from her father that financed each of her excursions. Although she was in charge of most aspects of her life, she never held her own purse strings. Without Hugh Bell’s support, Gertrude Bell’s legacy would never have been realized. His support, permission, and financing is what allowed her to travel. Today a young woman can travel independently and on the cheap—by teaching English abroad, working as an au pair, backpacking, being an exchange student—but in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, to travel at all was pure luxury. Even if that luxury included bug-infested tents, fevers, and meals of sour milk, the whole lot required a sizable investment. Horses had to be purchased, guides hired, cooks and servants employed, sheiks paid with handsome gifts, officials bribed, villages wooed, postage on a thousand letters home paid, and all the equipment a rigorous desert journey required—from pistols to bedding—purchased and packed. The Dieulafoys had a similar shopping list.

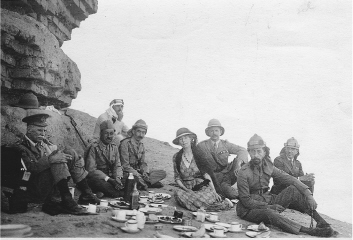

ABOVE :

Bell picnicking with Iraq’s King Faisal and company, 1922