Alcott, Louisa May - SSC 15

Read Alcott, Louisa May - SSC 15 Online

Authors: Plots (and) Counterplots (v1.1)

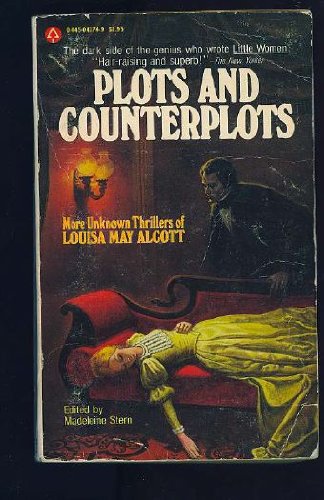

Plots and

Counterplots

Louisa May Alcott

MADELEINE STERN

[Jo

March] took to writing sensation stories, for in those dark

ages,

even all-perfect

America

read rubbish. She told no one, but concocted a “thrilling tale,” and

boldly carried it herself to . . . [the] editor of the Weekly Volcano. . . .

...

Jo rashly took a plunge into the frothy sea of sensational literature.

When

Louisa Alcott adopted the name of Jo March for her own role in Little Women,

she was not writing ‘‘behind a mask.” The creation is as vital as the creator

and many of the episodes in the life of this flesh-and-blood character are

autobiographical. The author herself once listed the “facts in the stories that

are true, though often changed as to time and place,” and that list included

“Jo’s literary . . . experiences.

The

exact nature of Louisa’s clandestine “literary experiences”—the discovery of

her pseudonym, the identification of her Gothic effusions— was all revealed in

Behind a Mask. There four of her thrillers were reprinted, suspenseful stories

that for over a century had lain unrecognized and unread in the yellowing pages

of once gaudy journals. Now the remaining sensational narratives written by Jo

March’s prototype have been assembled in a companion volume. Again readers may

revel in more stories by an L. M. Alcott masked in anonymity or in pseudo-

nymity. From the garret where the author wrote in a vortex flowed the tales

emblazoned in flashy weeklies circulated to campfire and hearthstone in the

1860’s. Now they can be devoured again—these suspenseful cliff-hangers which

are also extraordinary revelations of a writer who turns out to be not simply

“The Children’s Friend” but a delver in darkness familiar with the passions of

the mind.

As

a professional who could suit the demands of diverse tastes, Louisa Alcott

disdained a precise duplication of her themes and characters. Her repetitions

are repetitions with variations. Her heroines— those

femmes

fatales who could manipulate whole families—are in this second volume femmes

fatales with a difference. Motivated still by jealousy or thwarted love,

ambition or innate cruelty, they now take on the texture of marble beneath

whose cold white surface the fires of passion flame or are banked. Louisa

Alcott’s marble women have their variants too: sometimes they have encased

themselves in marble the better to execute their purposes; sometimes an attempt

is made by a demonic character to transform them into marble. Whatever the nature

of their seeming frigidity, they are all extraordinary actresses, mistresses of

the arts of disguise who use their props—their bracelets or ebony caskets,

their miniatures and keys or bloodstained slippers—with histrionic skill. In

one of the narratives of Plots and Counterplots, Alcott’s most evil heroine has

been painted, the dancer Virginie Varens of “V. V.,” a creature seductive,

viperish, manipulating, who with a lovely bit of irony wins even as she loses

in the end.

Here

too will be found themes that go beyond the tamer shockers of Behind a Mask:

the child-bride theme, which had a strange lure for the creator of Little

Women, stemming perhaps from her early disastrous experience as a domestic in

the service of the elderly James Richardson of Dedham; the theme of murder,

which appears here in gory splendor; the theme of insanity, which is traced

through many variations from a hereditary curse to an attempt at manipulated

insanity, a black plot to madden a benighted heroine. The whole psychology of manipulation

is presented with singular power in these tales, the drive of one dark mind to

shape another, the Pygmalion theme in a somber setting. Finally, in addition to

the lure of evil and violence, mental aberrations and mind control, Plots and

Counterplots will offer to devotees of “The Children’s Friend” another sinister

theme—drug addiction and experimentation. The creator of

jo

March was skilled not only in the wholesome delights of apples and ginger

cookies but in the more macabre delights of opium and hashish.

Like

the stories presented in Behind a Mask, these narratives with their purple

passages and their scarlet motifs had their sources not only in the gaudy

Gothics which their author devoured but also in the life she had led, the

observations she had made,

the

fantasies she had

dreamed. Louisa Alcott was to some extent the Jo March who “like most young

scribblers . . . went abroad for her characters and scenery; and banditti,

counts, gypsies, nuns, and duchesses appeared upon her stage. . . .

“As

thrills could not be produced except by harrowing up the souls of the readers,

history and romance, land and sea, science and art, police records and lunatic

asylums, had to be ransacked for the purpose. . . . Eager to find material for

stories, and bent on making them original in plot, if not masterly in

execution, she searched newspapers for accidents, incidents, and crimes; she

excited the suspicions of public librarians by asking for works on poisons; she

studied faces in the street, and characters, good, bad, and indifferent, all

about her; she delved in the dust of ancient times for facts or fictions . . .

and introduced herself to folly, sin, and misery.”

She

delved also into her own “ancient times,” dredging up especially the

ingredients of those “Comic Tragedies” she had penned as a girl with her sister

Anna and produced on the stage of the

Hillside

barn in

Concord

. Love scenes and direful lines, dramatic

confrontations and disguises, desertions and suicides, magic herbs, love

potions and death phials that had been the staples of “The Unloved Wife” or

“The Captive of Castile” could be introduced again with alterations. If they

had once chilled the blood of an audience of illustrious neighbors, now, having

undergone a subtle sea change, they could chill the blood of subscribers to

flamboyant weeklies.

Other

episodes in Louisa Alcott’s past could be served up to readers of sensational

stories. In 1858, after her sister Lizzie’s death, she had seen a light mist

rise from the body. Seven years later a misty apparition would arise from a

fictional Alcott grave. Before the Civil War, Louisa had heard tales of

Jonathan Walker, whose hand had been branded with the letters S.S. for “Slave

Stealer.” For the prototype of Jo March’s

Blarney

stone Banner or Weekly Volcano the initials

V. V. would be tattooed upon an imaginary wrist. A short period during the

summer of 1860, when Louisa had cared for “a young friend during a temporary

fit of insanity,” would be put to use for lurid excursions into nightmarish derangements.

Louisa

Alcott’s service as a Civil War nurse in the

Union

Hotel

Hospital

,

Georgetown

, was followed by an illness that provided

her with one of the most interesting sources for her tales of violence and

revenge. After some six weeks of nursing she succumbed to typhoid pneumonia, a

severe attack of which she wrote, “I was never ill before this time, and never

well afterward.” The bout was accompanied by sinister dreams from which the

patient would awaken unrefreshed. Since those dreams, that fevered delirium,

would be interwoven into the fabric of her blood-and-thunders, they merit an

attention less medical than literary.

The

most vivid and enduring was the conviction that I had married a stout, handsome

Spaniard, dressed in black velvet, with very soft hands, and a voice that was

continually saying, 'Tie still, my dear!” This was Mother, I suspect; but with

all the comfort I often found in her presence, there was blended an awful fear

of the Spanish spouse who was always coming after me, appearing out of closets,

in at windows, or threatening me dreadfully all night long. . . .

A

mob at

Baltimore

breaking down the door to get me, being

hung for a witch, burned, stoned, and otherwise maltreated, were some of my

fancies.

Also being tempted to join Dr. W. and two of the

nurses in worshipping the Devil.

Also tending millions

of rich men who never died or got well.

After

three weeks of delirium “the old fancies still lingered, seeming so real I

believed in them, and deluded Mother and May with the most absurd stories, so

soberly told that they thought them true.” As her father reported in a letter

to Anna in January, 1863, Louisa “asked me to sit near her bedside, and tell

her the adventures of our fearful journey home [from

Georgetown

] . . . and enjoyed the story, laughing over

the plot and catastrophe, as if it were a tale of her imagining.”

The

tales of her imagining would still pay the family bills. The economic necessity

that had prompted the stories in Behind a Mask prompted those in Plots and

Counterplots. At times the only breadwinner of the family, Louisa Alcott set

about liberating that family from debt with her thrillers, and in so doing she

achieved a psychological catharsis that liberated her own mind from its

phantasmagorias. Her father had observed in “the elements of your temperament”

both the “Spaniard” and the “Saxon.” The “Spanish” elements were surely in the

ascendancy when she reeled off her “‘thrilling’ tales, and mess up my work in a

queer but interesting way.” She was at this time a compulsive writer, dashing

off her narratives “like a thinking machine in full operation.” Stories

simmered in her brain demanding to be written. “My pen,” she despaired, “will

not keep in order, and ink has a tendency to splash when used copiously and

with rapidity.” Once she wrote, “

Liberty

is a better husband than love to many of

us,” and often she “longed for a crust in a garret with freedom and a pen.”

It

was to the office of the Weekly Volcano that Jo March boldly ventured with a

thrilling tale and “bravely climbed two pairs of dark and dirty stairs to find

herself

in a disorderly room, a cloud of cigar smoke, and

the presence of three gentlemen, sitting with their heels rather higher than

their hats.” If “Louisa Alcott” is read for “Jo March,” then The Flag of Our

Union may be read for the Weekly Volcano, and for the three gentlemen in a

cloud of cigar smoke, the three colorful Boston publishers, Messrs. Elliott,

Thornes and Talbot, whose “disorderly room” was part of the Journal Building at

118 Washington Street.

Louisa

Alcotts

first contribution to The Flag of Our Union

was also the story that flaunted her most unregenerate heroine. “V. V.: or,

Plots and Counterplots” “By a Well Known Author” appeared in February, 1865, to

titillate readers and divert them from news of the war that would end two

months later. A shocker it was, with its heady ingredients—poison in an opal,

footprints left by a murderess, drugged coffee, a feigned pistol duel,

theatrical props against sketchy theatrical backgrounds of a fancied Spain or

India, Paris or Scottish estate. But it is less for its plots and counterplots

moving relentlessly on to the “eclat” of a “grand denouement” that “V. V.”

becomes a fascinating narrative. It is, as in most of the Alcott thrillers, the

nature of the heroine that captures the intense interest of the reader.

Virginie

Varens is no Jo March. All Spanish, she bears no traces of her authors “Saxon”

elements. “A sylph she seemed” in the greenroom of a

Paris

theater, a seventeen-year-old dancer

“costumed in fleecy white and gold . . . flushed and panting, but radiant with

the triumphs of the hour.” Her cousin and dancing partner, that sinewy,

animated flame of fire, Victor, has set his mark upon her—two dark letters

“tattooed on the white flesh” of her wrist, the monogram V. V., which she

conceals by means of a bracelet fastened with a golden padlock. Virginie is

already

a

fdle if not a femme fatale with many

suitors, including a viscount who offers her an establishment and infamy, and the

Scot Allan Douglas who offers her an honorable name and a home. “Mercenary,

vain, and hollow-hearted” as well as conniving and ambitious, Virginie accepts

the latter. Thereupon the “fiery and fierce” Victor, enraged with jealousy,

“reckless of life or limb,” takes “the short road to his revenge,” and “with

the bound of a wounded tiger” stabs the bridegroom. As for the heroine, one

“night of love, and sin, and death” has transformed her into wife, widow, and,

as it turns out, mother too.

So

the curtain rises upon a melodrama of deceit and death. Because she is

motivated primarily by social ambition, Virginie Varens appears more innately

evil than her competitors—those powerful and passionate