Alan Turing: The Enigma (111 page)

Read Alan Turing: The Enigma Online

Authors: Andrew Hodges

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Science & Technology, #Computers, #History, #Mathematics, #History & Philosophy

Churchill had promised blood, toil, tears and sweat – and this was one promise which the politicians had kept. Half a million of Alan Turing’s compatriots had been sacrificed ten years before, without much choice in their fate; to have the luxury of choice in matters of integrity and freedom was itself a great privilege. Only the ‘heads in the sand’ assumptions of 1938 had allowed him into such a position in the first place, and his position in 1941 was one for which many would have given all they had. Ultimately he could not have complained. The implications had proliferated, and arrived at a remorseless contradiction. It was his own invention, and it killed the goose that laid the golden eggs.

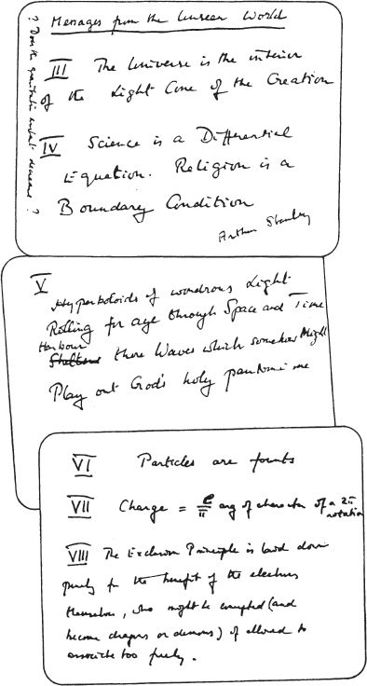

No one remotely mindful of such considerations could have wanted to make a fuss; and neither in any case could he speak of such things – that was the very point. Only in obscure clues and jokes could they emerge. In March 1954 he sent to Robin four last postcards.· They were headed ‘Messages from the Unseen World’, an allusion to Eddington’s 1929 book

Science and the Unseen World

. Robin kept only the last three, here shown:

It would be misleading to suggest that he had made any discovery in these jottings, but the underlying thoughts were in line with the developments of the 1950s and 1960s.

III. ‘Arthur Stanley’ is Eddington, and the first postcard alluded to cosmological questions. The ‘light cone’ is an important idea in relativity theory. Einstein’s ideas were based on the concept of a point in space-time, this meaning a precise location in space at a precise instant of time. Imagining this as an instantaneous spark, the future ‘light cone’ of such a point is traced out by the expanding sphere of light from that spark.

By the ‘Creation’ he would mean the ‘big bang’; it had been known since the 1920s that there were models of an expanding universe that agreed with Einstein’s general theory of relativity, and in 1935 H.P. Robertson, whose lectures Alan attended at Princeton, had further developed the theory of them. Unfortunately the astronomers’ observations of the galactic recession did not seem to be consistent with the Einstein theory, and only in the mid-1950s was the discrepancy eliminated. This was one reason why in 1948 H. Bondi, T. Gold and F. Hoyle had suggested a new theory involving ‘continual creation’ which eliminated the ‘bang’. Alan might have heard Gold speak about it at the Ratio Club in November 1951. But apparently it did not deflect him from the earlier view, soon to be established much more firmly.

The emphasis on a description

using light cones was not a trivial insight. Such an emphasis was emerging in a quite different way through the work of A. Z. Petrov in 1954, was taken up by H. Bondi and F. A.E. Pirani later in the 1950s, and entered very strongly into the ideas of Roger Penrose, who in the early 1960s formulated new ideas about space-time. In fact a ‘Penrose diagram’ of the universe would draw it as ‘the interior of the Light Cone of the Creation’.

IV. Implicit here is the problem of physical determinism. Most physical laws, including Einstein’s, are in the form of a differential equation, relating instantaneous rates of change to one another in such a way that in principle, given the state of a physical system at one time, it can be predicted at a later time by adding up the changes over the period. In the context of cosmology this begs the question of what the ‘initial’ state of the universe was – it was a very Eddingtonian suggestion that the study of the differential equations of physics could only be half the story. Here again, the question of the nature of the initial ‘big bang’ was to be of growing significance in the renaissance of relativity theory.

V. Again the allusion is

to the problem of physical prediction – the wave functions somehow determining the events perceived as the pantomime of macroscopic life – and again the emphasis is on a description in terms of light rays. But the ‘hyperboloids’ suggest some quite novel geometric picture of his own, lost without trace.

VI. The reference to ‘founts’ suggests that he was thinking of describing the different elementary particles in terms of their corresponding symmetry groups–again in the mainstream of developments, although the picture as it unfolded in the 1960s was far more complicated than anyone would have known in 1954.

VII. He was certainly not the first to think that electric charge could be interpreted in terms of rotations, and his formula was too simple-minded. But 1954 saw the renewal of interest in ‘gauge theories’, which generalised this basic idea.

VIII. Often his letters closed with a brief line of personal comment, and this was surely the case here. There was certainly nothing new or speculative in scientific terms in this ‘message’, an allusion to the well-established Pauli Exclusion Principle. Back in 1929, when he read what Eddington had to say about the electron, Alan had noted the idea that the electrons of the universe had to be considered

en-masse

, not singly; the Pauli principle described an observed restriction on the collective behaviour which roughly speaking meant that no two electrons could be in the same place. Thus in each atom, the electrons would be stacked neatly in separate shells and orbits. As indeed he might have joked in 1929, it was like the House system that kept the boys from associating too freely. For their own benefit, of course:

Don’t you see, Dr Turing, we have to do this for your own protection....

The old Empire was giving way to the institutions of Oceania. None of Alan Turing’s friends saw this as a background that might be relevant to his death, nor saw him as playing the role of Casablanca after all. Not for about fifteen years would the various elements involved become mentionable at all, and even then no one could begin to put them together. There was no hushing-up operation in 1954 – it was not necessary, for no one thought anything nor asked any questions. The Wicked Witch of the West was caused no embarrassment, for the friends of Dorothy had nothing to go on. Few people on 7 June 1944, seeing the cycling civilian boffin, could have imagined a connection with the news of the great invasion: they did not need to know, nor want to know. Ten years later to the day, the links were literally unthinkable, and the death came as an individual hurt and loss, without suggesting any wider significance. Jung said:

62

Modern man protects himself against seeing his own split state by a system of compartments. Certain areas of outer life and of his own behaviour are kept, as it were, in separate drawers and are never confronted with one another.

Modern men had to protect themselves particularly carefully when they were confronted by Alan Turing, and they kept the compartments completely separate. So perhaps too did Alan Turing, when confronting his own situation.

Behind the singleminded Shavian figure that he cut, especially after the war, acting out in public a set of ideas with relentless intensity, and going to the stake like a modern Saint Joan, there had always been a more uncertain, contradictory person. Doubting Castle and Giant Despair had been his favourite passages in

The Pilgrim’s Progress

as a small boy, and his part in progress of mankind had been in keeping with them – the delectable mountains being few and far between. In particular there lay the uncertainty of all his relationships with institutions, neither fitting in, nor presenting a serious challenge. In this respect he shared something with many people deeply attracted to pure mathematics and science – never sure whether to regard social institutions as Erewhonian absurdities or as plain facts of life. Making a game out of anything, like G.H. Hardy (and like Lewis Carroll), he reflected the fact that mathematics could serve as protection from the world for one who was not so much blind to worldly affairs as only too sensitive to their horror. His off-hand, self-effacing humour also shared something with the response of so many gay men to an impossible social situation: in some ways directing a bold, satirical defiance at society – yet ultimately resigned to it.

For Alan Turing these elements were aggravated by the fact that he never quite fitted into the roles of mathematician, scientist, philosopher or engineer – nor into the tail-end of the Bloomsbury set, nor indeed into any kind of set, even the Wrong Set. It was often a case of

Laughter in the Next Room

for Alan Turing, for people never knew whether to include him or

not. Robin Gandy wrote

63

very soon after his death of how ‘Because his main interests were in things and ideas rather than in people, he was often alone. But he craved for affection and companionship – too strongly, perhaps, to make the first stages of friendship easy for him…’And he was more alone than anyone could ever see.

A self-taught existentialist, one who had probably never heard of Sartre, he had tried to find his own road to freedom. As life became more complicated it became less clear where this should lead him. But why should it have been clear? This was the twentieth century, in which the pure artist felt called upon to become involved, and which was enough to make any sensitive person acutely nervous. He had done everything he could to restrict his involvement to the simplest sphere, as he had also tried to keep true to himself, but simplicity and honesty had not protected him from the consequences of that involvement: far from it.

The British university world was as well insulated from the twentieth century as anyone could hope for; and so often it saw his eccentricities, not his vision, offered vague tributes to cleverness, not serious criticism of his ideas, and remembered the bicycle stories rather than the great events. But although nothing if not an intellectual, Alan Turing never truly belonged to the confines of the academic world. Lyn Newman, who had the advantage of seeing that world at close quarters but from outside, articulated

64

more clearly than anyone else this lack of an easy identity; she saw him as ‘a very strange man, one who never fitted in anywhere quite successfully. His scattered efforts to appear at home in the upper-middle class circles into which he was born stand out as particularly unsuccessful. He did adopt a few conventions, apparently at random, but he discarded the majority of their ways and ideas without hesitation or apology. Unfortunately the ways of the academic world which might have proved his refuge, puzzled and bored him…’ There was an ambivalence in his attitude to what was, despite all its concomitant deprivation, a privileged upbringing: he jettisoned most of the paraphernalia of his class but in inner self-confidence and moral responsibility remained the son of Empire. There was a similar ambiguity in his status as an intellectual, not only in his disdain for the more trivial functions of academic life, but in the mixture of pride and negligence with which he regarded his own achievements.

There was another uncertainty in his attitude to the privilege of being a man in a male-dominated world. In most ways he took it entirely for granted. It was a weak point of King’s liberalism that it rested upon wealth accumulated for the benefit of men alone, and he would have not been the person to question it. In conversation with Robin, who took a progressive line on the question of equal pay (the only issue, in this period, which kept feminism alive), Alan said simply that it would be unfair if women were off work having babies. Nor did he doubt that women would run round him clearing up the mess, and seeing to matters that he chose not to bother about

himself. In conversation with Don Bayley at Hanslope he mentioned how he had been engaged, that he had realised it ‘would not work’ because of his homosexuality, but also remarked that if he were ever to marry, it would be to someone non-mathematical, who would look after his domestic needs – a conventional attitude much closer to his family’s, and untrue to the way in which his friendship with Joan Clarke had developed. There was an unresolved contradiction here, at least at that stage of his life. He disliked the talking-down and triviality expected of men in ‘mixed company’ – and, no doubt, too, the pressure on him to display an erotic interest he did not feel – and largely avoided such social obligations. Yet when these constraints did not apply – especially, perhaps, with Lyn Newman, but to some extent with his own mother – he showed a mind more open to the other sex than that of many men to whom the word ‘women’ was a synonym for sexual possessions or distractions. Nor did he ever do more for male supremacy than to share in its institutions. He never sought to justify his homosexuality in terms of preferring the superior male, for instance, and when set against the speech and writing of what everyone called the age of the common man, his comments were remarkably free of the stream of hostility, implicit or explicit, than most men felt entirely free to direct at the encroachments or pretensions of women. Alan certainly spoke of ‘girls’ doing the menial work, and by implication cast them in the role of ‘slaves’ at Bletchley; yet this was simply the way things were, and if anything he was just a little more conscious of the inequity than were others who took it entirely for granted. He did nothing to change it, but then he had never sought to change the world, only to interpret it.