Airborne (1997) (35 page)

Authors: Tom Clancy

For the C-130H, the maximum cruising speed is 386 kn/715 kph. Typical cruising altitude is about 35,000 feet/10,668 meters, but the aircraft can reach over 40,000 feet/12,192 meters. The top speed ever recorded for the type, with a stiff tail wind, was 541 kn/1,003 kph, by an RC-130A. A more important performance characteristic for an airlifter is the minimum flight, or stall, speed. The lower the stall speed, the shorter the takeoff and landing roll needs to be for a particular aircraft. For the Hercules, this is approximately 80 kn/148 kph, which is about the same as a Cessna 150! The airframe is designed to safely withstand a stress of +3 Gs in the positive direction, or -1 G in the negative direction. Also, the huge rudder gives the pilot tremendous control authority in yaw (turning horizontally). The aircraft can actually make a flat turn, without banking. All in all, the Hercules is quite easy to fly, with lots of power and lift, and all the control authority that a pilot could want of an aircraft this size. The fine qualities were evident from the early flights of the prototype, and have only gotten better with the years.

That first flight of the YC-130A prototype was a sixty-one-minute hop from Burbank, California, to Edwards AFB on August 23rd, 1954. After the initial prototypes, all the production C-130s were built at Marietta, Georgia, about twenty miles northwest of Atlanta. The first flight of a production model came on April 7th, 1955, and nearly ended in disaster when a quick-disconnect fuel line on the No. 2 engine broke loose and started a fire that caused the wing to break off after landing. Soon repaired, the aircraft had a long, adventurous career tracking missiles and spacecraft, and later as a gunship in Vietnam, remaining in service until the early 1990s! Deliveries to the Air Force began in 1955, and by 1958 the C-130A was found in six Troop Carrier Squadrons (later designated Tactical Airlift Squadrons [TASs]).

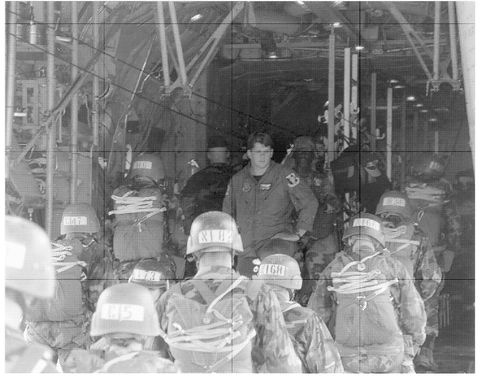

A “chalk” of 82nd Airborne Paratroops loaded aboard a C- 130H Hercules, preparing for a training jump under the watchful eye of an Air Force Loadmaster. A force of several hundred C-130s provide the bulk of America’s Medium Airlift muscle.

JOHN D. GRESHAM

From the start, the Hercules had an unusual career within the U.S. military. The first operational employment of the C-130 came in 1957, when President Eisenhower dispatched troops of the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock, Arkansas. This federal effort to enforce court-ordered school desegregation against the opposition of a defiant state governor started the tradition of the C-130 being used in non-combatant/civil/relief efforts. The Hercules’ major overseas deployment came in 1958 during the Lebanon Crisis, delivering supplies to Marines who landed at Beirut to support a friendly government threatened by civil war. The first combat airborne assault for USAF C-130s came in 1960 in the Congo (now known as Zaire), where they delivered a battalion of French paratroops. The French were headed to the remote town of Stanleyville (now Kisangani) to rescue civilians and diplomats threatened by a local uprising. Following this, when Chinese troops invaded disputed regions on the northern borders of India in 1962, President Kennedy quietly dispatched a squadron of C-130s to help the Indian Army reinforce its remote Himalayan outposts. The Herks flew thousands of troops and tons of supplies into Leh, where a mountain-ringed 5,000-foot /1,524-meter runway of pierced steel plate (PSP) at an altitude of 10,500 feet/3,200 meters was the only link to the outside world. Even more astounding feats were ahead for the C-130, though.

In 1963, the U.S. Navy actually conducted C-130

carrier

landing and takeoff trials onboard USS

Forrestal

(CV-59). The Chief of Naval Operations wanted to know if the big transport could be used to deliver supplies to carriers operating far from friendly bases. The aircraft was a KC-130F tanker on loan from the U.S. Marine Corps, and the Naval aviator in command was Lieutenant (later Admiral) James H. Flatley III, with the assistance of a Lockheed engineering test pilot, Ted Limmer, Jr. At a weight of 85,000 lb/38,555 kg, the aircraft came to a complete stop in a mere 270 feet/82.3 meters, about twice the wing span of the Hercules! This required some fancy flying—the aircraft reversed thrust on the propellers 3 feet/1 meter above the deck. At maximum load, the plane required a takeoff roll of only 745 feet/227 meters of the carrier’s 1,039-foot/316.7-meter flight deck. On one occasion, the plane stopped just opposite the captain’s bridge with “LOOK MA, NO HOOK” painted in big letters on the side of the fuselage. The Navy never followed up on this promising experiment (they bought the Northrop Grumman C-2 Greyhound instead), but the Herk’s unique ability to take off and land on a carrier remains to challenge the imagination of Joint Special Operations planners down in Tampa.

carrier

landing and takeoff trials onboard USS

Forrestal

(CV-59). The Chief of Naval Operations wanted to know if the big transport could be used to deliver supplies to carriers operating far from friendly bases. The aircraft was a KC-130F tanker on loan from the U.S. Marine Corps, and the Naval aviator in command was Lieutenant (later Admiral) James H. Flatley III, with the assistance of a Lockheed engineering test pilot, Ted Limmer, Jr. At a weight of 85,000 lb/38,555 kg, the aircraft came to a complete stop in a mere 270 feet/82.3 meters, about twice the wing span of the Hercules! This required some fancy flying—the aircraft reversed thrust on the propellers 3 feet/1 meter above the deck. At maximum load, the plane required a takeoff roll of only 745 feet/227 meters of the carrier’s 1,039-foot/316.7-meter flight deck. On one occasion, the plane stopped just opposite the captain’s bridge with “LOOK MA, NO HOOK” painted in big letters on the side of the fuselage. The Navy never followed up on this promising experiment (they bought the Northrop Grumman C-2 Greyhound instead), but the Herk’s unique ability to take off and land on a carrier remains to challenge the imagination of Joint Special Operations planners down in Tampa.

The war in Southeast Asia tested the Hercules under the most difficult combat conditions imaginable. All told C-130s transported about two thirds of all the troops and cargo tonnage moved by air inside South Vietnam. Frequently, the Herks flew through mortar and rocket fire into narrow 2,500-foot strips carved out in the jungle, and when there were no airfields, they delivered cargo by parachute. The C-130 played an especially vital role supplying the Marines’ epic defense of the besieged mountain base of Khe Sanh in 1968. The Vietnamese Army’s airborne units even conducted a few classic parachute assaults (the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division fought exclusively as “leg” infantry) during the war. Eventually, one of the last aircraft to escape the fall of Saigon in April of 1975 was a South Vietnamese C-130 carrying a load of 452 people (this is as much as a fully loaded Boeing 747 jumbo jet!): soldiers, airmen, children, and dependents. Amazingly, all arrived safely in Thailand. Now, the Vietnamese are not large people by our standards, but this all-time Herk passenger record was an amazing overload, and a heroic feat of airmanship by Major Phuong, the pilot. At the end of the conflict, the North Vietnamese Air Force captured about thirty C-130s in various states of disrepair, and despite the lack of spares, managed to keep a few flying until the late 1980s, even using some of them as bombers in Cambodia. They now sit, stripped and forlorn, on the old runways at Ton Son Nhut and Bien Hoa, unless they have been sold for scrap.

For the Hercules, Vietnam was a chance to prove how versatile it was. So it is only natural that the C-130 had a part in one of the most significant innovations of the Vietnam War: the development of the gunship. The idea was to load up a large transport aircraft with heavy machine guns and even cannons, and use the weapons as an airborne firebase for supporting ground operations. Originally (from 1965 to 1967) the first gunships were vintage C-47s (known as “Puff the Magic Dragon,” after the popular song of the day), with a battery of side-firing machine guns. The concept was to fly a “pylon turn” around a fixed point on the ground, with the aircraft in a 30° bank circling the target. Operated by the 4th Air Commando Squadron, these first gunships proved highly effective in breaking up night attacks on remote outposts while using parachute flares to illuminate the battlefield. The sight of a great sheet of tracer fire pouring down from the sky had a dramatic psychological impact on friend and foe alike. So successful were the AC-47s that it was decided to build an even bigger gunship. The obvious choice for the airframes were elderly C-130As. A prototype AC-130 gunship arrived in South Vietnam on September 21st, 1967, and it was flown in combat until it practically fell apart. The prototype AC-130 had an improvised analog fire control computer, four 20mm M61 Vulcan cannon (similar to those fitted in modern fighter planes) firing through ports cut in the side of the fuselage, and four 7.62mm “miniguns” (a six-barrel rotary machine gun that fired up to six thousand rounds per minute). It also carried an early Texas Instruments Forward-Looking Infrared (FLIR) sensor, a night-image intensifier (“starlight scope”), and a side-looking radar that unfortunately proved to be ineffective against guerrilla bands in the jungle.

The Air Force was initially reluctant to divert C-130s from their vital airlift duties, preferring to convert obsolete twin-engine C-119 “Flying Boxcar” airframes for gunship duty. But the big Herky gunship proved so effective that commanders on the ground demanded more of the fire-spitting birds. More were ordered, and were quickly delivered for action in Vietnam. The AC-130 eventually evolved through a series of modifications, with increasingly heavy weapons and sophisticated sensors. Particularly important was the ASD-5 “Black Crow,” a radio-frequency direction finder developed in great secrecy to detect emissions from the old-fashioned ignition coils of Russian-made trucks on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Twenty-nine C-130 gunships served in Vietnam, with the 14th Air Commando (later Special Operations) Wing; six were lost to hostile ground fire.

There were many other variants of the Hercules developed during this period. They ranged from airborne tanker versions to mother ships for the highly classified “Buffalo Hunter” reconnaissance drones that were used extensively over Southeast Asia and Communist China. All this success had an obvious influence on the commercial and military export markets, and the Hercules has been a consistent favorite. Dozens of nations have bought hundreds of models (mostly C-130Hs) of the Hercules for both military and commercial purposes. One of the oddest export sales was one to Libya, before the embargo against Colonel Quadaffi took effect in 1973. When that action took place, a number of C-130H models had yet to be delivered. As a result, over two dozen years later, those Libyan Herks still sit baking in the Georgia sun, on a corner of the ramp in Marietta.

The late 1970s were a time of high adventure for the C-130, as various nations used the stubby transport for a new mission: Hostage Rescue. On July 4th, 1976, three C-130Hs of the Israeli Air Force, along with other support aircraft, raided Entebbe Airport in Uganda, rescuing nearly two hundred hostages that had been taken by Palestinian terrorists while aboard an Air France Airbus. A strike force of crack Israeli paratroops combat-assaulted into the airfield, retook the hostages, and then returned to Israel after suffering just a single casualty—Jonathan Netanyahu, the brother of the current prime minister of that country. After Entebbe, several other nations gave hostage rescue a try using C-130s as the transportation. When an Egyptian airliner was taken by terrorists to Nicosia Airport in Cyprus, the Egyptian government sent in their own commando team. While the assault was a bloody mess, most of the hostages survived. Not all the rescue missions that the C-130 went out on were successful, though, and the U.S. wound up being the loser.

On April 24th, 1980, the U.S. tried to rescue fifty-nine hostages taken when the American embassy in Tehran, Iran, was overrun in 1979. The plan relied on the Herk’s ability to land on short, unprepared runways. Flying low to evade Iranian radar, a force of C-130 tankers joined up with a small force of helicopters at “Desert One,” an isolated landing zone in the middle of nowhere. Unfortunately, technical problems with the helicopters caused the mission to be scrubbed before the assault on the embassy compound could be mounted. Then, while refueling on the ground during the extraction, an MH-53D helicopter collided with one of the C-130 tankers, igniting an uncontrollable fire. Eight Americans died and five more were injured, and the humiliation destroyed the Administration of President Carter.

The ashes of Desert One, as well as command problems during Operation Urgent Fury (the 1983 invasion of Grenada), led to a re-evaluation of U.S. special operations and joint command arrangements that paid off handsomely in the 1989 invasion of Panama and in 1990 and 1991 in the Gulf War. In every one of these operations, the C-130 played a key role, from dropping and delivering troops in Grenada and Panama, to hauling the cargo and troops that sustained the air campaign and “Hail Mary Play” during Desert Storm. Of particular note were the dozens of C-130s from nations other than the U.S. that supported coalition operations during Desert Shield/Storm. By having chosen the C-130 as their standard airlifter, the nations of the coalition were able to contribute a valuable resource without stressing the spares or maintenance pipeline of CENTAF.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the C-130 has been the backbone of the USAF theater mobility force, and has done an outstanding job. Unfortunately, the basic 1950s technology of the Herk makes the aircraft increasingly expensive to operate and maintain. In particular, while aircrew and mechanics were readily available and easy to train when the Herk was designed, today they represent a major share of an aircraft’s total life-cycle cost. Also, the C-130 lugs around a lot of weight that would not be there if it were being designed from scratch today. Design features such as computer network backbones and composite aircraft structures technologies had not even been envisioned when the YC-130A was on the Lockheed drawing boards. So the way was clear for a new generation of Hercules: the C-130J.

As early as May 1988, the Commander of the Military Airlift Command (now the Air Mobility Command, AMC) outlined requirements for a next-generation C-130. Unfortunately, the projected development costs were more than the Air Force budget would bear, so in December 1991 Lockheed decided to fund the development of the new Hercules variant, known as the C-130J, with the company’s own money. Have no doubt, though, that Lockheed Martin is going to make a load of money on this bird! The British Royal Air Force (RAF) and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) were the launch customers, and the U.S. military has also rapidly jumped onboard as well. Most notable has been the rapid commitment by the USMC for a new force of over a dozen KC-130 tankers. Also, the USAF has firm orders for two prototypes, options for 5 development aircraft, and a requirement for at least 150 units to replace aging C-130Es as they reach the end of their life cycle.

Other books

The Napoleon of Crime by Ben Macintyre

Zero Option by Chris Ryan

Corporations Are Not People: Why They Have More Rights Than You Do and What You Can Do About It by Jeffrey D. Clements, Bill Moyers

Harness by Viola Grace

One Good Reason (A Boston Love Story Book 3) by Julie Johnson

Beast by Cassie-Ann L. Miller

Time to Run by Marliss Melton

Deceived by King, Thayer

Farewell, My Lovely by Raymond Chandler