Airborne (1997) (32 page)

Authors: Tom Clancy

The one other guided weapon carried by the A-10 is the AIM-9M Sidewinder AAM, which is carried for self-defense against fighters and for shooting down the odd helicopter that may get in the way.

34

34

The tail of the A-10 consists of a broad horizontal stabilizer with a huge slab-sided vertical stabilizer with a rudder at each end. It was here that the ballistic tolerance in the Warthog design was taken to extremes. Either side of the tailplane can be shot away, and the A-10 will still be able to fly home! Also, the arrangement of the tail surface tends to shield the hot engine exhaust ducts from the view of ground-based observers, making it harder for a heat-seeking SAM to track the aircraft. Another thing that helps keep the Hog flying is that as much as possible, components of the A-10 are designed to be interchangeable between left and right (and between different aircraft). This enables repair crews to patch together one flyable Warthog from two or more damaged ones. This is just more of the whole “toughness” mentality that permeates the whole A-10 design from nose to tail.

Toughness is not just a characteristic of the A-10 and their pilots, though. It shows in how those ground crews service and support the Warthogs. There once was an aircrew joke about the ground technicians spreading corn on the ramp to “bring the hogs in at night.” However, every A-10 driver will tell you that it is those same skilled maintenance technicians that keep the Warthog fleet flying in the forward field conditions that it was designed to work from. The original concept of operations (CONOPS) for the A-10 was to have them spread out from a central home base, and then operate from forward operating bases (FOBs) that could be anything from a dirt airstrip to a section of the Autobahn. Small detachments of maintenance personnel would then go forward to refuel and rearm the big jets, and support any rapid repairs of equipment or battle damage that might occur. To this end, the A-10 was designed to be easy to support in the field. The aircraft has its own auxiliary power unit (APU, a miniature turbine engine buried in the aft fuselage), so it requires no external starter cart. There is even a telescoping retractable ladder built into the side of the fuselage, so the pilot can mount his steed without outside assistance.

So just what is involved when an A-10 comes in to be serviced? Well, the crew chief goes to the portside main landing gear sponson fairing, and opens the hinged forward cone. Located here there is a small diagnostic panel, as well as a single-point refueling receptacle. The crew chief gives the aircraft systems a quick check, as well as starting the process of refueling and rearming. At this point, the rest of the ground crew jumps into action to rearm the big jet and get the pilot ready for the next sortie. This process greatly resembles a NASCAR racing crew servicing a stock car in the pits before returning it to the track. In the whole turnaround process, only one specialized piece of ground equipment is needed, a big machine called the “Dragon,” which automatically reloads the A-10’s internal 30mm ammunition drum. Each FOB ground crew has a Dragon and the other things necessary to do “bare-bones” maintenance and replenishment between missions. Very rapidly, fuel is pumped, bombs and other weapons are loaded onto rails and racks, and the pilot is given a chance to go to the bathroom, grab a bite to eat, and look over the maps and get briefed for the next mission.

Short turnaround times between sorties are the key to this process, so that a maximum number of missions can be flown every day by each aircraft and pilot. This is done with field-level equipment and lots of backbreaking effort on the part of the ground crews. It is an amazing thing to watch the young men and women, all of them enlisted personnel and NCOs, loading tons of weapons and thousands of gallons of fuel in a matter of minutes, no matter the time of day, the heat or cold, rain or shine. Once the service break is over, the pilot mounts up, and another CAS mission is underway.

CAS missions were the rationale for the entire A-X program, and wound up being both loved and hated by the USAF leadership. Loved because CAS missions showed the Air Force “supporting” their Army brethren on the ground. This was the “proper” role of airpower during the development of the AirLand Battle doctrine of the late 1970s and early 1980s. At the same time, though, the USAF leadership hated the Warthogs, both for the money and personnel that they had to commit to the A-10s units and because their mission was heavily controlled by the Army. But whatever the USAF generals may have thought, the Warthog community has always loved their aircraft, and still see their mission as important, even in an age of PGMs. Their gypsy existence of operating out of FOBs harkens back to a simpler time when flying was fun and men flew the airplanes, not a bank of digital computers. To this day, the folks who fly the A-10 continue to be held in contempt by their supersonic brethren in the USAF, and they could care less! Perhaps the fast drivers just envy all the fun that their Hog-riding brethren seem to have. Whatever the case, the Warthog drivers have a diffi-cult and dangerous job to do, which has not gotten any easier since the original A-X requirement was written.

An A-10A Warthog being serviced by maintenance personnel. Being loaded are four AGM-65 Maverick Air-to-Surface missiles, which provide the A-10 with a heavy, long-range punch.

OFFICIAL US. AIR FORCE

PHOTO FROM THE COLLECTION

OF ROBERT F. DORR

PHOTO FROM THE COLLECTION

OF ROBERT F. DORR

The basic mission that the A-10 was designed for was daylight low-altitude ground attack on the European Central Front during the Cold War. If World War III had ever broken out, squadrons home-based in England would have rotated to austere FOBs in Germany and other NATO partner countries, where the aircraft would then be dispersed and camouflaged in the woods. They could have even operated from straight sections of the Autobahn had that been necessary. While each FOB detachment would have been between four and eight A-10s, the basic A-10 tactical formation has always been the pair. This has an element lead and a wingman, operating within visual contact of each other for mutual support. In bad weather that can mean flying a tight formation, with wingtips only a few feet apart. Two pairs often operate as a “four-ship.” Don’t let the small numbers put you off, though. During just one day of operations during Desert Storm, a pair of particularly aggressive Hog drivers destroyed over two dozen Iraqi tanks in front of the Marine units advancing on Kuwait City.

Early on in the A-10’s operational history, the Hog drivers began to do joint training with Army AH-1 Cobra attack helicopters. The A-1Os flying as low as 100 feet/30 meters, would first take out enemy mobile antiaircraft guns (like the deadly ZSU-23-4) and mobile SAM launchers (such as the SA-8 Gecko and SA-9 Gaskin) with AGM-65 Maverick missiles, allowing the attack helicopters to safely “pop up” above ridgelines, village housetops, or tree lines to fire their own TOW antitank missiles. As the helicopters dropped back behind cover, the Warthogs would then wheel around in sharp low-altitude turns to strafe the immobilized enemy columns with cannon fire. If bad weather prevented using Mavericks, A-10s would rely on antiarmor cluster bombs. These tactics eventually evolved into an “intruder” philosophy of operations, which had the Warthogs operating over preplanned areas known as “kill boxes,” which were essentially free-fire zones. This was the basic operating philosophy that the A-10 community took with them to the Persian Gulf for Desert Storm.

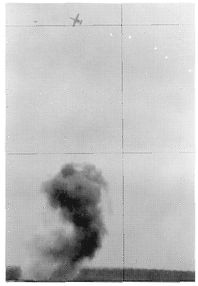

An A-10A Warthog pulls out of a bombing run over the Fort Polk range. The white dots behind the aircraft are flares, designed to decoy the infrared guided surface-to-air missiles.

OFFICIAL U.S. ARMY PHOTO

Finding targets can be a real challenge in the Warthog. With no targeting aids other than their own eyeballs, one vitally important skill for every A-10 pilot is managing the unruly folded paper maps on his knee board, since the A-10 lacks one of the fancy moving-map displays common on aircraft like the F-15E Strike Eagle. A-10 pilots frequently have to depend on forward air controllers (FACs) on the ground and in other aircraft to locate the enemy formations and guide the Warthogs to the best attack position. This FAC “cuing” process has been refined down to a terse “nine-line brief” based on military map coordinates. Each run by the A-10s is laid out in detail, with the following data points being given to each pilot by the FAC just prior to the run-in:

1. Location of the initial point (IP) for starting an attack.

2. Heading from IP to targets.

3. Elevation of targets.

4. Distance from IP to the targets.

5. Target descriptions (artillery positions, tank columns, truck convoys, etc.).

6. Map coordinates of the targets.

7. Positions of nearby friendly forces.

8. Best direction to leave the target area.

9. Any other information that might help the pilot survive.

By formalizing the process of target designation and properly coordinating run-ins, the chances of a “blue-on-blue” or “friendly fire” incident are minimized.

These tactics did not develop overnight. On the contrary, from the time the 23rd Fighter Wing (the first overseas A-10 unit) stood up at RAF Bentwaters in the late 1970s, they were constantly refining their craft, always working to find new ways to better use their Hogs.

Throughout the 1980s, A-10 units were frequently deployed to trouble areas like Korea and the Caribbean, but always after the tensions were over. They helped hold the line during the final decade of the Cold War, and were almost out of business when a call to go to a

real

war arrived.

real

war arrived.

August of 1990 saw the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, and the A-10 community were quickly up to their snouts in the crisis. One quick note about this, though. There has always been an apocryphal story that General Chuck Horner, the commander of the U.S. 9th Air Force and the Central Command Air Forces (CENTAF), did not want the Warthogs in the Persian Gulf. Nothing could be further from the truth, though.

35

Deployment of A-10 units had always been part of the 9th Air Force/CENTAF deployment schedule, and they got their alert order to move only six days after the first USAF units had started deploying to the Gulf. As General Horner would tell you, he had to get aircraft capable of getting air superiority into the theater first, and the Warthogs just had to wait their turn.

35

Deployment of A-10 units had always been part of the 9th Air Force/CENTAF deployment schedule, and they got their alert order to move only six days after the first USAF units had started deploying to the Gulf. As General Horner would tell you, he had to get aircraft capable of getting air superiority into the theater first, and the Warthogs just had to wait their turn.

This does not mean that everything was easy when they got there. The deployment to Saudi Arabia took almost twice as long as a comparable F-15 or F-16 unit because of the Warthogs’ slow cruising speed, and when they arrived, the conditions they encountered were decidedly austere. Living in tent cities with outdoor showers was the rule for the A-10 units. But like the other units assigned to CENTAF, they worked hard and made their main base at King Fahd International Airport (near Dhahran) a suitable home.

The real problem the Warthog community had was selling themselves and their capabilities to the CENTAF planning staff. The bulk of the early Desert Storm air campaign targets were of a “strategic” type, requiring the kind of all-weather targeting and precision-guided munitions capabilities that were inherent to aircraft like the F-111F Aardvark, F-117 Nighthawk, and A-6E Intruder.

36

On the surface, this would appear to leave little for other attack aircraft like the A-10s, F-16s, and AV-8B Harriers to do, though nothing could be further from the truth. From the very beginning of the Desert Storm air campaign planning process, it had been planned to keep a constant, twenty-four-hour-a-day pressure on the Iraqis, especially their fielded forces in the Kuwaiti Theater of Operations (KTO). When the advocates for the A-10 made their capabilities known to the CENTAF staff, the Warthogs quickly began to get mission tasking for operations in southern Iraq and Kuwait.

36

On the surface, this would appear to leave little for other attack aircraft like the A-10s, F-16s, and AV-8B Harriers to do, though nothing could be further from the truth. From the very beginning of the Desert Storm air campaign planning process, it had been planned to keep a constant, twenty-four-hour-a-day pressure on the Iraqis, especially their fielded forces in the Kuwaiti Theater of Operations (KTO). When the advocates for the A-10 made their capabilities known to the CENTAF staff, the Warthogs quickly began to get mission tasking for operations in southern Iraq and Kuwait.

By the time Desert Shield turned into Desert Storm, a total of 144 A-10s had been deployed to Saudi Arabia, forming the 23rd and 354th Tactical Fighter Wings (Provisional). Despite the terrible weather and difficult operational conditions in the Gulf during the winter of 1991, overall A-10 mission availability during the Gulf War was rated at 95 percent, which was higher than peacetime levels at well-equipped home bases!

Other books

Don’t Forget to Remember Me by Kahlen Aymes

One Hot Winter Break (Yardley College Chronicles Book 2) by Sharon Page

Lo que me queda por vivir by Elvira Lindo

The Complete Guide to English Spelling Rules by John J Fulford

Squelch by Halkin, John

South Beach: Hot in the City by Lacey Alexander

The Fairy-Tale Detectives (The Sisters Grimm, Book 1) by Michael Buckley

Hidden Riches by Nora Roberts

The Slender Man by Dexter Morgenstern

Hush Little Baby by James Carol