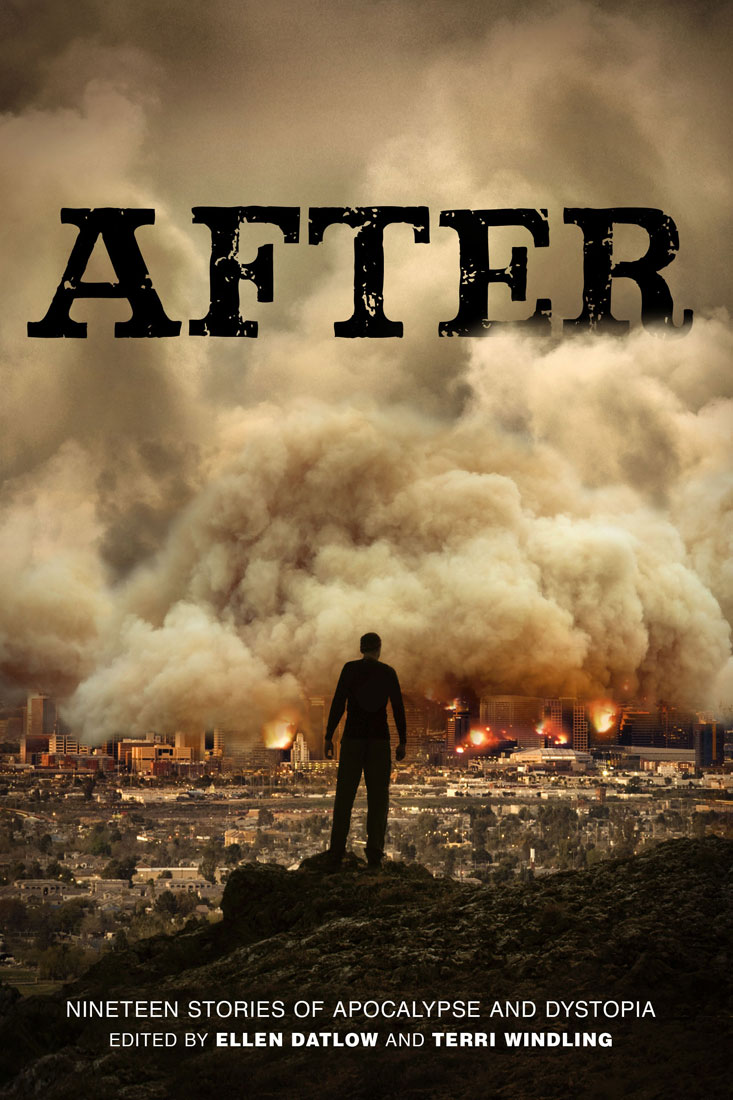

After: Nineteen Stories of Apocalypse and Dystopia

Read After: Nineteen Stories of Apocalypse and Dystopia Online

Authors: Ellen Datlow,Terri Windling [Editors]

Introduction © 2012 by Terri Windling

“The Segment” copyright © 2012 by Genevieve Valentine

“After the Cure” copyright © 2012 by Carrie Ryan

“Valedictorian” copyright © 2012 by N. K. Jemisin

“Visiting Nelson” copyright © 2012 by Katherine Langrish

“All I Know of Freedom” copyright © 2012 by Carol Emshwiller

“The Other Elder” copyright © 2012 by Beth Revis

“The Great Game at the End of the World” copyright © 2012 by Matthew Kressel

“Reunion” copyright © 2012 by Susan Beth Pfeffer

“Blood Drive” copyright © 2012 by Jeffrey Ford

“Reality Girl” copyright © 2012 by Richard Bowes

“How Th’irth Wint Rong by Hapless Joey @ homeskool.guv”

copyright © 2012 by Gregory Maguire

“Rust with Wings” copyright © 2012 by Steven Gould

“Faint Heart” copyright © 2012 by Sarah Rees Brennan

“The Easthound” copyright © 2012 by Nalo Hopkinson

“Gray” copyright © 2012 by Jane Yolen

“Before” copyright © 2012 by Carolyn Dunn

“Fake Plastic Trees” copyright © 2012 by Caitlín R. Kiernan

“You Won’t Feel a Thing” copyright © 2012 by Garth Nix

“The Marker” copyright © 2012 by Cecil Castellucci

Afterword © 2012 by Terri Windling

All rights reserved. Published by Hyperion, an imprint of Disney Book Group. No part

of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic

or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information address

Hyperion, 114 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011-5690.

ISBN 978-1-4231-7006-8

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Introduction by Genevieve Valentine

- The Segment

- After the Cure by Carrie Ryan

- Valedictorian by N. K. Jemisin

- Visiting Nelson by Katherine Langrish

- All I Know of Freedom by Carol Emshwiller

- The Other Elder by Beth Revis

- The Great Game at the End of the World by Matthew Kressel

- Reunion by Susan Beth Pfeffer

- Blood Drive by Jeffrey Ford

- Reality Girl by Richard Bowes

- How Th'irth Wint Rong by Hapless Joey @ Homeskool.guv by Richard Bowes

- Rust with Wings by Steven Gould

- Faint Heart by Sarah Rees Brennan

- The Easthound by Nalo Hopkinson

- Gray by Jane Yolen

- Before by Carolyn Dunn

- Fake Plastic Trees by Caitlín R. Kiernan

- You Won't Feel a Thing by Garth Nix

- The Marker by Cecil Castellucci

- Afterword

- About the Contributors

- About the Editors

For Victoria Windling-Gayton and Isobel Gahan, two young women with indomitable spirits

W

ELCOME TO

AFTER

, A VOLUME OF BRAND-NEW DYSTOPIAN

and post-apocalyptic tales for young adult readers by some of the very best writers

working today—ranging from best-selling, award-winning authors to rising young stars

of the dyslit field.

Before we go any further, however, perhaps we’d better stop and define our terms…which

is going to put us in dangerous territory; for blistering arguments about what should

and shouldn’t be labeled dystopian fiction have consumed whole Internet forums, convention

panels, and book review columns. There is, alas, no single definition that all of

us who love this kind of fiction can agree on.

To some folks (including most YA publishers), dyslit is a broad, inclusive genre of

tales that take place in darkly imagined futures: ranging from stories that explore

the dangers of repressive governments and societies gone bad to books whose plots

unfold in bleak, savage, or oppressive post-apocalypse settings. In this usage, the

dyslit label conveys more about a story’s overall

tone

than its plotline (or subtext of societal critique): the worlds depicted are

dark

ones, in which protagonists must struggle for physical and/or moral survival.

Others folks (including most literary critics) reach back to the classical definition

of dystopian literature, which is far more specific: tales of utopias gone wrong.

In this view, post-apocalyptic novels are dystopian

only

if the narrower definition applies—otherwise they are a genre of their own, albeit

one that is closely related, and read by many of the same readers. “In a dystopian

story,” writes John Joseph Adams (editor of

Brave New Worlds: Dystopian Stories

, an excellent collection of traditionally dystopian fiction), “society itself is

typically the antagonist; it is society that is actively working against the protagonist’s

aims and desires.” Now, this may true in

some

post-apocalyptic tales, but it’s certainly not true in all of them, for many take

place in post-disaster settings where human society has broken down altogether. To

dystopian purists, such books do not belong on dyslit lists.

As for us, although we respect the purists’ view, we’ve chosen to take a broader road

in the creation of this anthology, including

both

dystopian and post-disaster tales (as well as stories that fall on the spectrum between)

in order to reflect the wide range of dyslit beloved by teen readers today. As the

popular dyslit author Scott Westerfeld has said (in his essay “Teenage Wastelands”

for Tor.com): “…in the YA universe, the terms ‘post-apocalyptic’ and ‘dystopian’ are

often used interchangeably. This grates the pedant’s soul, and yet is understandable.

From a teenager’s point of view, a blasted hellscape and a hypercontrolled society

aren’t so different. Or rather, they’re simply two sides of the same coin: one has

too much control, the other not enough. And, you may be shocked to hear, teenagers

are

highly

interested in issues of control.”

Exactly.

Our anthology sprang from a simple idea: to seek out writers who share our love for

dystopian and post-apocalyptic tales, and to ask them to please write stories for

us about what happens

after

.

After what?

A disaster of any kind: political, ecological, technological, sociological…the choice

was entirely up to the writer. It could be

after

a nuclear war or a medical pandemic;

after

a scientific discovery that resulted in unforeseen and dire consequences;

after

aliens land, or society crumbles, or the very last drop of oil runs out…It could

be after

anything

so long as the changes provoked are calamitous, fundamental, and long lasting. “We’re

not looking for tales focused on the disaster,” we said, “but tales that tell us what

happens

next

: what life is like for young people who are growing up in calamity’s wake, or in

‘perfect societies’ gone wrong, or in the ruins of their elders’ mistakes.”

Our intrepid writers went away with this assignment and came back with the amazing

stories that follow: frightening, fascinating, mind-bending stories about dark future

worlds that could be our own if something (sometimes the smallest thing) goes badly,

irreparably wrong.

These stories approach the “after” theme from a variety of directions—some of them

straightforward in the telling, and some of them sly, tricksy, and surprising. Like

the field of dystopian literature itself, the stories draw upon the tropes of several

overlapping genres: science fiction, fantasy, horror, mystery, surrealism, and satire…with

a bit of romance (

apocalyptic

romance, of course!) thrown in for good measure.

In the worlds conjured by the stories that follow, you’ll find floods, famine, and

pestilence; you’ll find monsters, horrors, despair, and devastation. And also, in

the darkness, bright sparks of courage and resistance.

Much like the world we live in.

W

HEN

M

ASON SHOWED ME THE SCRIPT SIDES FOR THE CHILD

soldier, I jumped on it.

“Think about this,” he said. “The segment could be huge. Is that how you want to make

your career?”

He talked a big game, but this segment was special. He had to know it, too; I was

the only one at our agency he’d even talked to about it.

I said, “I’ll take my chances.”

“All right,” he said. He looked serious, but I was pretty sure he was just full of

it.

The best gig I’d had so far was the front half of a black bear for a nature documentary.

It was on cable.

I’m not complaining—you have to pay your way at the agency, and rent be not proud—but

I needed to earn some more, soon, and “bear half ” didn’t set your career on fire.

Face time was an upgrade. And this wasn’t some bit part as a muddy orphan in an establishing

shot. This was the big time.

This was the evening news.

That night I walked under our painted motto (Let Those Who Would Be Fooled, Be Fooled)

into the dining hall, packed with kids from the Lowers that the agency hired out as

sympathetic faces on news segments for the Uppers to go watch when they were feeling

generous.

I sat down, grinning, next to Bree.

“I’m in the audition pool for a soldier.”

She barely looked up from her vegetable mash. “Oh? Congratulations.”

“Yeah,” I said. “It’s big. Investor backing for the cause, too, so the pay is pretty

solid.”

“Wonderful,” she said. “I was beginning to worry you’d aged out of your best work.

It’s nice they’re skewing older on something.”

I was sixteen. Bree was nineteen, and kind of a bitch.

“What’s the story?”

“My brother is missing,” I said, “and he was the last thing I had left of home. Now

I’m fighting the people who took him since I’m dead inside anyway, grenades exploding

on us any moment, blah, blah, blah. They wanted someone who can handle a gun, not

for crying or anything.”

Bree’s fork wasn’t moving anymore. “Is this for some newspaper?”

I grinned. “The evening news.”

Now she was looking up, her head angled by instinct to catch the best light on her

face. “What?”

“Yup.” I shrugged like it was nothing. “I was handpicked. If the segment breaks big,

they’ll probably have to retire me.”

Bree looked stunned. After a second, she recovered and said, “Dream big.”

“I’m going to get it,” I said.

She smiled. “I’m sure,” she said. “And if that doesn’t pan out, there’s always a place

for you on

Naturewise

.”

She was acting like I’d been the

back

half of the bear.

I stood. “I’m going to rehearse.”

“Break a leg,” said Bree, like she meant it.

When I was still a kid, Bree had gotten a gig as a grieving bride whose husband was

killed by government troops on his way up the stairs of the church.

(She was still in the dorms with me, then; she wouldn’t be a teacher until after that

segment.)

It was supposed to be a small part, a background tableau in the middle of a bigger

story, but Bree wasn’t a person who played small parts.

In the on-scene segment with the news man in front, she had clutched her veil in her

fists as she wept over the body of the guy who’d been her husband.

He was from some other agency. I hadn’t seen him since—she’d kept him in the spotlight

too long, and his face was too famous after that. She’d taken his career down. Bree

played for keeps.

In the grainy newspaper shots (meant to have been taken by a wedding guest), Bree

had cradled his head in her lap and lowered her mouth to his mouth, their lips almost

touching but not quite.

(“You’re not supposed to kiss before marriage in that country,” Bree told me the night

before filming, when everyone else was asleep.

“There’s nowhere to go with that,” I said.

Bree said, “Watch me.”

At the time I hated that we shared a dorm. Our beds were pressed up against the walls,

separated except for her voice, and I was trapped listening to her; but there was

no question that the advice had done me good.)

The bride segment had been aimed at a regional station, to drum up sympathy for the

insurgents in a couple of key cities, that could be pushed over the edge of public

opinion by a sob story on the news.

(Stations hired out their news stories now. It was easier and safer than going looking

for news, and our stories never went sour on you the way they did if you trusted them

out in the wild.

And it’s not like audiences knew the difference. To the Uppers, one tragedy on their

television was as surreal as the next. Let those who would be fooled, be fooled.)

Bree was paid for a segment on the independent channel, and a picture in the locally

edited newspaper.

She ended up on the cover of

Planet

magazine.

(“The segment tested so well they’re thinking of extending the war,” Bree told me.

“The Uppers love to watch a cause they can donate to.”

Her voice sounded strange.)

She had one of the first editions framed above her bed. It was a close-up, her tear-stained

face half hidden by a gold silk veil; her gaze sliding sideways with smeary, kohl-rimmed

hazel eyes looking out at the viewer.

The headline: the Weeping bride on the mountain path.

The article was ten pages about the plight of the fleeing insurgents. The quotes came

from the insurgents, too;

Planet

was classy enough to do research like it was still real. They’d even called the agency

to get quotes right from Bree and not from our publicity office, because Bree had

done such a good job with the part that they didn’t want the performance to be diluted.

(I listened in, of course. I hated her, but I knew when to take notes from a master.)

“I can never kiss him, until we meet in Heaven,” Bree had sighed into the office phone,

her voice shaking, and on the other end of the line the

Planet

guy muttered, “Holy shit, that’s great,” and started typing.

(Her hands were shaking, too; Bree never did anything by halves.)

The article won a Pulitzer. Before the year was out, that government fell apart, and

the insurgents got the revolution they’d paid for.

At the agency, they treated Bree like she sweated gold nuggets, and added the leader

of the insurgents to their list of references for when the next guys called up the

agency looking for the kind of story that couldn’t happen by accident.

They had pulled Bree out of the audition pool for good after the story faded, because

there was no way people would ever forget her face after that.

If you ask me, she was doomed from the beginning with eyes like that, anyway. No hiding

those; I don’t care how big your crowd shot is.

Now Bree had a look like she thought this was all beneath her. She shouldn’t: she

was still here, teaching. (The insurgents were good for publicity, but they hadn’t

paid so great. Wherever the Uppers’ money had gone, none of it had made it to Bree.)

She was the only person at the agency who had ever been retired because of success.

So far.

Bree knew how to act above it all, but everybody has their tells, and I knew I’d gotten

to her when I saw she’d signed up for phone privileges.

She made a lot of calls; she was a Lower, but she had parents on the outside. They

came to visit once a year, and brought books for her (Bree could read), and told her

how happy they were that she had done well for herself.

It hadn’t made her any friends, but I guess when you have parents, you can take or

leave the rest.

I pulled a muscle in calisthenics to get out of the session early. It took some doing

to wrench my arm without breaking it, but it was my only option. No good faking anything.

The downside of working in a casting agency was that everybody was on to your act.

“Ice that down at the nurse, now,” said Miss Kemp, as I headed out. “You’d better

look like you know how to carry a gun at the audition tomorrow.”

I wasn’t worried. I was tall for a girl, and wiry. I could carry half a black bear

suit; I could manage a gun.

“Don’t worry,” I told her, and grinned. (I had all my teeth. My smile was priceless,

even on Miss Kemp.)

The phone room was on the office floor, so it was easier for snoopy adults to catch

snoopy students. Not that it mattered. With Bree, you never had to get any closer

than the landing.

“Mother,” she was saying, “you’ve got to do something about the part they want this

girl for.”

Bingo.

Her voice, tense and serious, echoed down the hall. “It’s not fair. She’s sixteen,

but she’s never done anything! I don’t know why they’re doing this at all. There’s

got to be someone else who could use her.”

One success can really turn a petty person sour, I thought.

“Yeah, she’s good enough,” Bree said. “Can’t you buy her out? She’ll find some other

way to earn out of her contract.” And a second later, meaner, “Well, decide faster.”

I snuck back down the stairs before the call was over. Listening to someone jealous

themselves into a heart attack wasn’t as fun as I’d thought.