Adrift (26 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

The Miami Coast Guard is contacted by a ship off Puerto Rico that has sighted a small white boat, dismasted and adrift. The Coast Guard requests that the ship board the vessel. Negative. The boat is already lost to sight. The ship will not return. Description? White, twenty feet long, no markings, no one on board.

Solo

was beige. She had a wide dark blue stripe all around the topsides and dark blue cabin sides. Her name was painted across her transom. A fourteen-inch-high number 57 was plastered on each side and on her deck.

Somehow the two boats are taken to be the same. Officially, "

Napoleon Solo

has been located with no one on board." In California, a ham operator picks up the message from the Long Beach Coast Guard and begins to notify those who have been keeping their ears open. Messages flock out.

Solo

is no longer missing.

My brother demands more information. Was the life raft on board? Was any other equipment visible? Were there any signs of possible piracy? What was the wreck's position? He wants to go check it out himself. The New York Coast Guard knows nothing of the matter. It proves impossible to get any information at all from them. Something funny seems to be going on. While my arm trails through the water stroking my doggies, my mother envisions me murdered by pirates or rotting in some fascist prison cell.

Indeed, something funny is going on. The Coast Guard begins to issue statements. At first they say that the message that

Solo

has been located must be a bogus one made by a ham operator without a license. Then they hint that it may have been sent by the Callahans themselves in order to stir up some action.

Slowly and meticulously, my family trace the message through the ham net to Germany and then to California, and then from Long Beach to Miami through the holes in the Coast Guard net. The truth has escaped. Still, the false message is being carried on the seafarer's net and is received by a friend of mine in Bermuda. The New York Coast Guard instructs the Callahans that if they want the message canceled, they will have to arrange it themselves. Finally it is done.

By this time my family have done everything they can to calculate my approximate position and get a search going. They have tried in vain to get the armed forces to fly over the areas of high probability during their routine patrols and maneuvers. They have also failed in attempts to gain the use of spy satellites that have the acuity to photograph trash cans from space. Not only is the target not specific in this case, but the area to be searched is at least 200 miles across, or 31,400 square miles. If each photo covered 900 square feet, or 30 feet on a side, it would take over a billion photos to check out the area. In every direction in which my family have turned to get a physical search under way, they have found a roadblock.

There is little else for them to do but to continue writing to politicians and maintain private contact with shipping companies. Although most people now feel I must have perished long ago, my parents decide that only if I don't show in six months will they consider the matter laid to rest. My brother Ed readies himself to return to his family in Hawaii. It is now just a waiting game for us all.

Finally, on April 20, the Coast Guard decides to rebroadcast for another week the message that

Solo

is overdue.

APRIL

16

DAY

71

The past few days have passed ever so slowly and I have been growing progressively more dim and depressed. We should have reached the islands days ago. We couldn't have passed between them, could we? No, they are too close together. I'd have seen at least one. And the birds still come at me from the west. When do I use the EPIRB for the last time? Even with the short range it must now have, the massive daytime Caribbean air traffic will hear the signal. But I must wait until I see land or can last no longer.

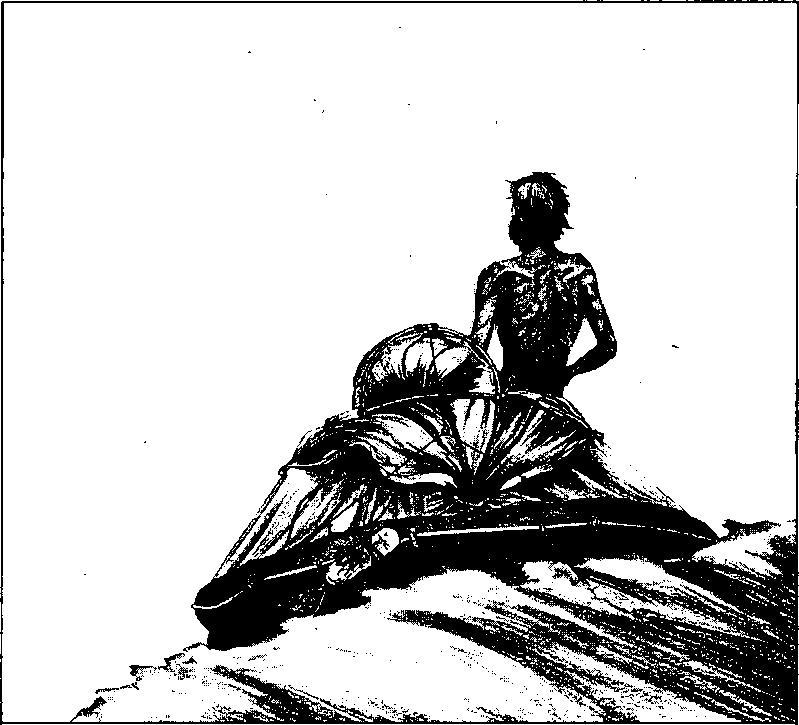

I am beginning to doubt everythingâmy position, my senses, my life itself. Maybe I am Prometheus, cursed to have my liver torn out each day and have it grow back each night. Maybe I am the Flying Dutchman, doomed to sail the seas forever and never rest again, to watch my own body rot and my equipment deteriorate. I am in an infinite vortex of horror, whirling deeper and deeper. Thinking of what I will do when it is all over is a bad joke. It will never be over. It is worse than death. If I were to search the most heinous parts of my mind to create a vision of a real hell, this would be the scene, exactly.

The last solar still has completely blown, just like the one before. The bottom cloth has rotted and ripped away. I have a full stock of water, but it will go quickly. Rainfall is my only well now.

APRIL

18

DAY

73

I continue to take note of the positive signs of approaching landfall. The tiger dorados have gone. A five- or ten-pound mottled brown fish, a tripletail, has lumbered around

Rubber Ducky

for two days. I've tried to hit it, but I've been impatient. I hurried the shots and only managed to poke it twice, driving it away. There have been more sooty birds in the sky, and the frigates continue to reel about overhead. I've grabbed two snowy terns, which landed for a short rest and received a permanent sleep. I've seen another ship, but at night and very far off. Somehow all of these changes do little for my continued depression. I am the Dutchman. I arise still feeling asleep. There is no time for relaxation, only time for stress. Work harder. Do more. Must it last forever?

I strike my fishing pose yet again. My aching arms grasp the few ounces of plastic and aluminum, the butter knife tied on like a caveman's stone point, but indubitably less effective. Now I can hold the pose only for a minute or so, no longer. The dorados brush against my knees as I push all of my weight down on one knee, then the other. They turn their sides to me as if wanting to show off the target area, and they swing out to the left and right or flip around deep below. Occasionally they wiggle their heads so near the surface that the water welters up. Perhaps one will rise and speak to me like the flounder in the fairy tale. Often I wait a microsecond too long, and the few square inches of bull's eye melt away into the dark water, which is just starting to brighten as the sun rises. This time I strike home, the battle rages, and I win again. The emerald elders court behind the lines like generals who are smart enough not to join in the melee any more.

Clouds race across my world, gray and smeared, too light for a heavy burst of rain, but the light sprinkles and misty air, combined with wave spray stirred up by the wind, prevent my fish from drying properly. Temporarily though, the stock of food allows me to concentrate my energy on designing new water-catchment systems. The first is simple. I stretch plastic from the cut-up still along the shaft of the spear gun. I can hold it out, away from the sheltering canopy, pulling a corner with my mouth. Next I set the blown still on the bow. I punch it into a flat, round plate and curl up the edges like a deep-dish pizza pie. Even in light showers, I can see that the two devices work. A fine mist collects into drops, that streak into dribbles, that run into wrinkled, plastic valleys, where 1 can slurp them up. I must move quickly to tend to each system and collect water before it's polluted by waves or the canopy. I am far enough west that the clouds are beginning to collect, and occasionally I see a "black cow," as some sailors call squally cumulus, grazing far off, its rain streaking to earth.

I stick with the routine that I've followed for two and a half months. At night I take a look around each time I awaken. Every half hour during the day, I stand and carefully peruse the horizon in all directions. I have done this more than two thousand times now. Instinctively I know how the waves roll, when one will duck and weave to give a clear view for another hundred yards or half a mile. This noon a freighter streams up from astern, a bit to the north of us. The hand flares are nearly invisible in the daylight, so I choose an orange smoke flare and pop it. The dense orange genie spreads its arms out and flies off downwind just above the water. Within a hundred feet it has been blown into a haze thinner than the smoke of a crowded pub. The ship cuts up the Atlantic a couple of miles abeam and smoothly steams off to the west. She

must

be headed to an island port.

APRIL

19

DAY

74

I work all the rest of the day and all of the morning of April 19 to create an elaborate water collection device. Using the aluminum tubing from the radar reflector and my last dead solar still, I make

Rubber Ducky

a bonnet that I secure to the summit of the canopy arch tube. The half circle of aluminum tubing keeps the face of the bonnet open and facing aft. A bridle adjusts the angle of the face, which I keep nearly vertical, and the wind blows the bonnet forward like a bag. I fit a drain and tubing that I can run inside to fill up containers while I tend to the other water collectors.

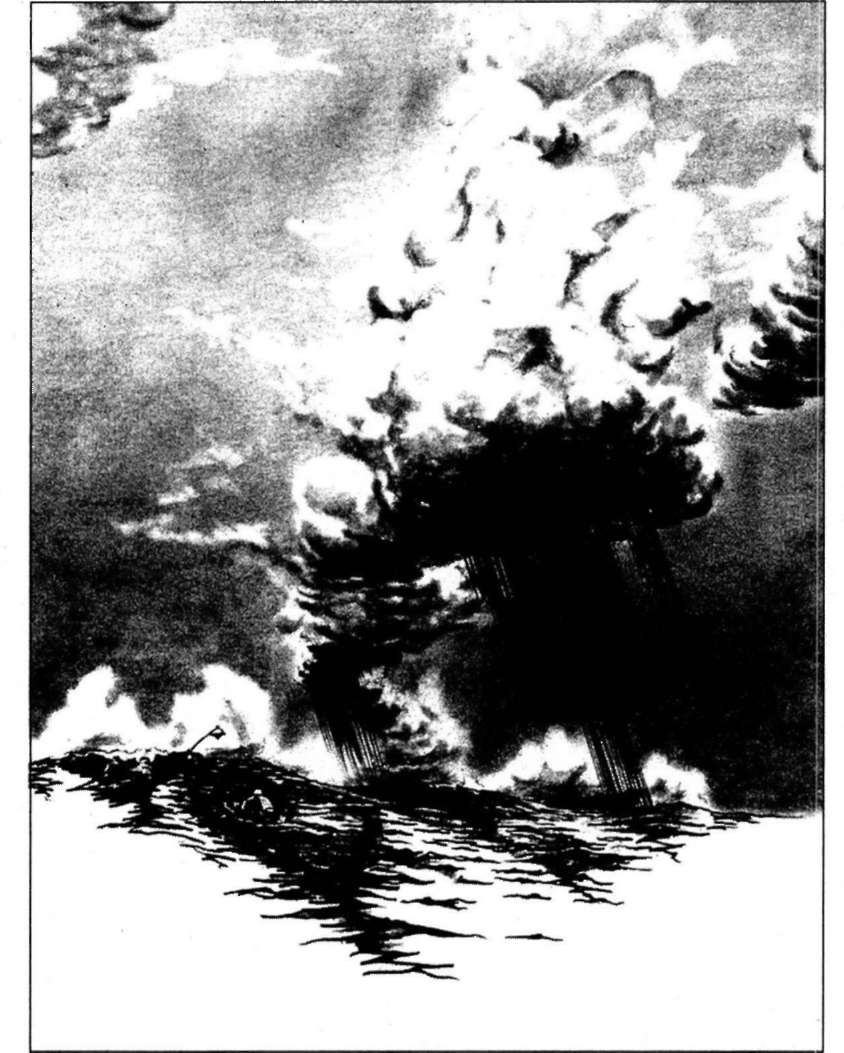

For hours I watch white, fluffy cumulus rise up from the horizon and slowly pass. Sometimes they band together and form dense herds running in long lines. Those that have grazed over the Atlantic long enough grow thick and muscular, rearing up to great billowing heights, churning violently, their underbellies flat and black. When they can hold no more, their rain thunders down in black streaks that lash the sea. I chew upon dried sticks of dorado awaiting the test of my new tools.

But it seems that the paths of the squalls are bound to differ from mine. Sometimes a long line of clouds passes close by. I watch the wispy edges swirl above me and feel a few drops or a momentary sprinkle coming down. It's just enough to show me that my new water collection gear is very effective. I'm convinced that I'll collect several pints, maybe even a gallon, if I can just get directly in the path of a single heavy shower. It's one thing to have a tool and quite another to be in a position to use it. My eyes wander from the horizon to the sky. I'm so tired of always awaiting something.

Seventy-five daysâApril 20. With the drizzle and the salt spray, my dorado sticks have grown pasty rather than drying. I'm astonished that the dried sticks from one of the first dorados that I caught still seem to be fine. Only a slight whitish haze covers the deep amber, woody interior.

APRIL

20

DAY

75

For an hour in late afternoon, I watch a drove of clouds run up from the east. I can tell that they're traveling a little to the south of my course. As they rise up and charge onward, I ready myself, swallowing frequently, though there is no saliva to swallow. I try to wish them into running me down, but they ignore me and begin to sweep by about a mile away, clattering and flashing with lightning. Four separate heavy columns of rain pour down, so dense that they eclipse the blue sky behind. I watch tons of pure water flowing down like aerial waterfalls. If only I could be just a mile from where I am. No sips, no single mouthfuls, but an overflow of water I could guzzle. If only

Ducky

could sail instead of waddle. I have missed. My collection devices are bone dry and flutter in the wind.

Using the aluminum tubing from the radar reflector and the plastic from the last dead solar still, I create an elaborate water collection deviceâa bonnet that sits on the peak of the arch tube. I bend and lash together the aluminum tubing into a semicircle with an axle that runs across the bottom. All of the ends are well padded to prevent damage to the raft's canopy or arch tube. This framework keeps the face of the bonnet open and facing the wind. The plastic still is lashed to the framework and blows forward like a small sail. I've fitted a piece of tubing into the bottom of the bonnet and led it inside so that when it rains I can keep busy filling containers. The bridle tied to the stern keeps the bonnet upright, but I can adjust the angle so that the face can point directly into the rain. Also note that the water collection cape is beginning to deteriorate and tear. I've pulled up the rusty gas bottle and have it tied to the exterior handline. For hours each day I stand and keep watch often gazing ahead hoping for the cloud formations to finally reveal land.