A Wrinkle in Time (Madeleine L'Engle's Time Quintet) (9 page)

Read A Wrinkle in Time (Madeleine L'Engle's Time Quintet) Online

Authors: Madeleine L'Engle

The shadow was still there, dark and dreadful.

Calvin held her hand strongly in his, but she felt neither strength nor reassurance in his touch. Beside her a tremor went through Charles Wallace, but he sat very still.

He shouldn’t be seeing this, Meg thought. This is too much for so little a boy, no matter how different and extraordinary a little boy.

Calvin turned, rejecting the dark Thing that blotted out the light of the stars. “Make it go away, Mrs Whatsit,” he whispered. “Make it go away. It’s evil.”

Slowly the great creature turned around so that the shadow was behind them, so that they saw only the stars

unobscured, the soft throb of starlight on the mountain, the descending circle of the great moon swiftly slipping over the horizon. Then, without a word from Mrs Whatsit, they were traveling downward, down, down. When they reached the corona of clouds Mrs Whatsit said, “You can breathe without the flowers now, my children.”

Silence again. Not a word. It was as though the shadow had somehow reached out with its dark power and touched them so that they were incapable of speech. When they got back to the flowery field, bathed now in starlight, and moonlight from another, smaller, yellower, rising moon, a little of the tenseness went out of their bodies, and they realized that the body of the beautiful creature on which they rode had been as rigid as theirs.

With a graceful gesture it dropped to the ground and folded its great wings. Charles Wallace was the first to slide off. “Mrs Who! Mrs Which!” he called, and there was an immediate quivering in the air. Mrs Who’s familiar glasses gleamed at them. Mrs Which appeared, too; but, as she had told the children, it was difficult for her to materialize completely, and though there was the robe and peaked hat, Meg could look through them to mountain and stars. She slid off Mrs Whatsit’s back and walked, rather unsteadily after the long ride, over to Mrs Which.

“That dark Thing we saw,” she said. “Is that what my father is fighting?”

“Yes,” Mrs Which said. “Hhee iss beehindd thee ddarrkness, sso thatt eevenn wee cannott seee hhimm.”

Meg began to cry, to sob aloud. Through her tears she could see Charles Wallace standing there, very small, very white. Calvin put his arms around her, but she shuddered and broke away, sobbing wildly. Then she was enfolded in the great wings of Mrs Whatsit and she felt comfort and strength pouring through her. Mrs Whatsit was not speaking aloud, and yet through the wings Meg understood words.

“My child, do not despair. Do you think we would have brought you here if there were no hope? We are asking you to do a difficult thing, but we are confident that you can do it. Your father needs help, he needs courage, and for his children he may be able to do what he cannot do for himself.”

“Nnow,” Mrs Which said. “Arre wee rreaddy?”

“Where are we going?” Calvin asked.

Again Meg felt an actual physical tingling of fear as Mrs Which spoke.

“Wwee musstt ggo bbehindd thee sshaddow.”

“But we will not do it all at once,” Mrs Whatsit comforted them. “We will do it in short stages.” She looked at Meg. “Now we will tesser, we will wrinkle again. Do you understand?”

“No,” Meg said flatly.

Mrs Whatsit sighed. “Explanations are not easy when they are about things for which your civilization still has no words. Calvin talked about traveling at the speed of light. You understand that, little Meg?”

“Yes,” Meg nodded.

“That, of course, is the impractical, long way around. We have learned to take shortcuts wherever possible.”

“Sort of like in math?” Meg asked.

“Like in math.” Mrs Whatsit looked over at Mrs Who. “Take your skirt and show them.”

“La experiencia es la madre de la ciencia.

Spanish, my dears. Cervantes.

Experience is the mother of knowledge.”

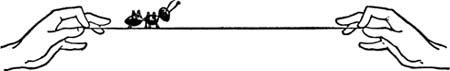

Mrs Who took a portion of her white robe in her hands and held it tight.

“You see,” Mrs Whatsit said, “if a very small insect were to move from the section of skirt in Mrs Who’s right hand to that in her left, it would be quite a long walk for him if he had to walk straight across.”

Swiftly Mrs Who brought her hands, still holding the skirt, together.

“Now, you see,” Mrs Whatsit said, “he would

be

there, without that long trip. That is how we travel.”

Charles Wallace accepted the explanation serenely. Even Calvin did not seem perturbed. “Oh,

dear

,” Meg sighed. “I guess I

am

a moron. I just don’t get it.”

“That is because you think of space only in three dimensions,” Mrs Whatsit told her. “We travel in the fifth dimension. This is something you can understand, Meg. Don’t be afraid to try. Was your mother able to explain a tesseract to you?”

“Well, she never did,” Meg said. “She got so upset about it. Why, Mrs Whatsit? She said it had something to do with her and Father.”

“It was a concept they were playing with,” Mrs Whatsit said, “going beyond the fourth dimension to the fifth. Did your mother explain it to you, Charles?”

“Well, yes.” Charles looked a little embarrassed. “Please don’t be hurt, Meg. I just kept at her while you were at school till I got it out of her.”

Meg sighed. “Just explain it to me.”

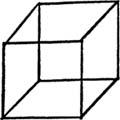

“Okay,” Charles said. “What is the first dimension?”

“Well—a line:——————”

“Okay. And the second dimension?”

“Well, you’d square the line. A flat square would be in the second dimension.”

“And the third?”

“Well, you’d square the second dimension. Then the square wouldn’t be flat anymore. It would have a bottom, and sides, and a top.”

“And the fourth?”

“Well, I guess if you want to put it into mathematical terms you’d square the square. But you can’t take a pencil and draw it the way you can the first three. I know it’s got something to do with Einstein and time. I guess maybe you could call the fourth dimension Time.”

“That’s right,” Charles said. “Good girl. Okay, then, for the fifth dimension you’d square the fourth, wouldn’t you?”

“I guess so.”

“Well, the fifth dimension’s a tesseract. You add that to the other four dimensions and you can travel through space without having to go the long way around. In other words, to put it into Euclid, or old-fashioned plane geometry, a

straight line is

not

the shortest distance between two points.”

For a brief, illuminating second Meg’s face had the listening, probing expression that was so often seen on Charles’s. “I see!” she cried. “I got it! For just a moment I got it! I can’t possibly explain it now, but there for a second I saw it!” She turned excitedly to Calvin. “Did you get it?”

He nodded. “Enough. I don’t understand it the way Charles Wallace does, but enough to get the idea.”

“Sso nnow wee ggo,” Mrs Which said. “Tthere iss nott all thee ttime inn tthe worrlld.”

“Could we hold hands?” Meg asked.

Calvin took her hand and held it tightly in his.

“You can try,” Mrs Whatsit said, “though I’m not sure how it will work. You see, though we travel together, we travel alone. We will go first and take you afterward in the backwash. That may be easier for you.” As she spoke the great white body began to waver, the wings to disolve into mist. Mrs Who seemed to evaporate until there was nothing but the glasses, and then the glasses, too, disappeared. It reminded Meg of the Cheshire Cat.

—I’ve often seen a face without glasses, she thought;—but glasses without a face! I wonder if I go that way, too. First me and then my glasses?

She looked over at Mrs Which. Mrs Which was there and then she wasn’t.

There was a gust of wind and a great thrust and a sharp shattering as she was shoved through—what? Then darkness; silence; nothingness. If Calvin was still holding her hand she could not feel it. But this time she was prepared for the sudden and complete dissolution of her body.

When she felt the tingling coming back to her fingertips she knew that this journey was almost over and she could feel again the pressure of Calvin’s hand about hers.

Without warning, coming as a complete and unexpected shock, she felt a pressure she had never imagined, as though she were being completely flattened out by an enormous steam roller. This was far worse than the nothingness had been; while she was nothing there was no need to breathe, but now her lungs were squeezed together so that although she was dying for want of air there was no way for her lungs to expand and contract, to take in the air that she must have to stay alive. This was completely different from the thinning of atmosphere when they flew up the mountain and she had had to put the flowers to her face to breathe. She tried to gasp, but a paper doll can’t gasp. She thought she was trying to think, but her flattened-out mind was as unable to function as her lungs; her thoughts were squashed along with the rest of her. Her heart tried to beat; it gave a knifelike, sidewise movement, but it could not expand.

But then she seemed to hear a voice, or if not a voice, at least words, words flattened out like printed words on paper, “Oh, no! We can’t stop here! This is a

two

-dimensional planet and the children can’t manage here!”

She was whizzed into nothingness again, and nothingness was wonderful. She did not mind that she could not feel Calvin’s hand, that she could not see or feel or be. The relief from the intolerable pressure was all she needed.