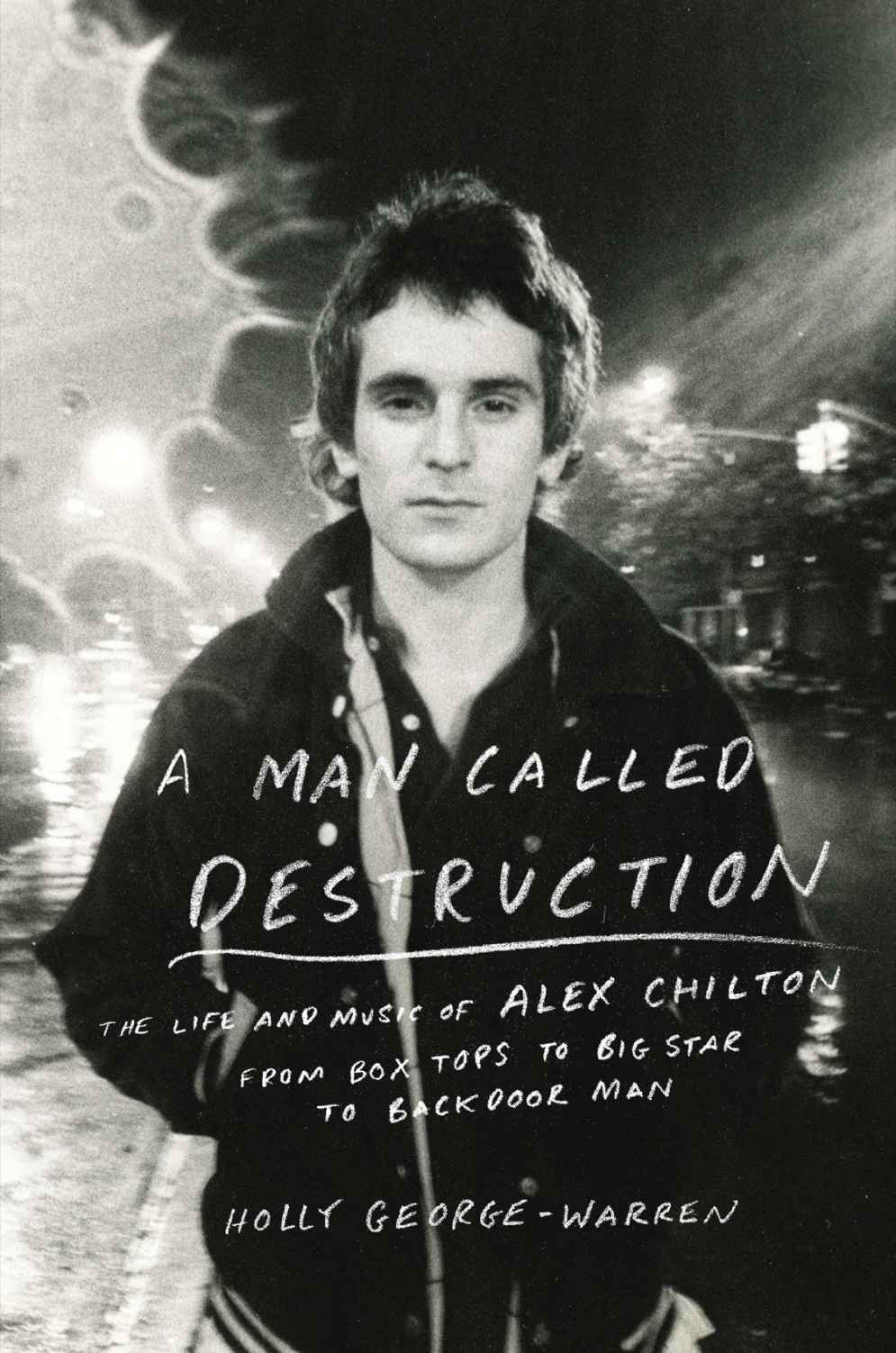

A Man Called Destruction: The Life and Music of Alex Chilton, From Box Tops to Big Star to Backdoor Man

Authors: Holly George-Warren

ALSO BY HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN

Public Cowboy No. 1: The Life and Times of Gene Autry

Punk 365

Grateful Dead 365

The Cowgirl Way: Hats Off to America’s Women of the West

Honky-Tonk Heroes and Hillbilly Angels: The Pioneers of Country & Western Music

Cowboy: How Hollywood Invented the Wild West

Shake, Rattle & Roll: The Founders of Rock & Roll

John Varvatos: Rock in Fashion

(with John Varvatos)

The Road to Woodstock

(with Michael Lang)

It’s Not Only Rock ’n’ Roll

(with Jenny Boyd)

How the West Was Worn: A History of Western Wear

(with Michelle Freedman)

Bonnaroo: What, Which, This, That, the Other

(editor)

The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats

(editor)

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: The First 25 Years

(editor)

Farm Aid: A Song for America

(editor)

The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll

(coeditor

)

Martin Scorsese Presents the Blues: A Musical Journey

(coeditor)

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Holly George-Warren

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Photograph

here

by Stephanie Chernikowski

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

George-Warren, Holly.

A man called destruction : the life and music of Alex Chilton, from Box Tops to Big Star to backdoor man / Holly George-Warren.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-698-15142-0

1. Chilton, Alex. 2. Rock musicians—United States—Biography. I. Title.

ML420.C4737G46 2014

782.42166092—dc23

[B] 2013041158

Version_1

For Robert and Jack

Chapter 1

The Chiltons of Virginia and Mississippi

Chapter 5

From Moondog to Deville

Chapter 6

America’s Youngest Hitmaker

Chapter 9

“I Slept with Charlie Manson”

Chapter 14

You Get What You Deserve

Chapter 22

Behind the Magnolia Curtain

“

Somewhere along the line I figured out that if you only press up a hundred copies of a record, then eventually it will find its way to the hundred people in the world who want it the most.”

Alex Chilton uttered those words to English musician Epic Soundtracks, a cult figure in his own right, in 1985. Nearly thirty years later—during the summer of 2013—New York’s Central Park hosted a concert celebrating

3rd/Sister Lovers

, one of Alex’s groundbreaking, yet commercially unsuccessful albums. The following night, the documentary

Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me

premiered in Manhattan, then opened around the country. Both events resulted in a flurry of Alex Chilton–related Facebook exchanges, blogging, and media coverage. The Central Park performance marked the pinnacle of eight months of concerts over a thirty-month span organized by former Chilton collaborator Chris Stamey. In U.S. cities as well as around the world, participants ranged from members of R.E.M. and Wilco to Robyn Hitchcock and M. Ward. A few weeks later, some of Alex’s noisiest acolytes, the Replacements, played their first gig in twenty-two years with their 1987 ode “Alex Chilton” now reaching an audience of fifty thousand, thanks to the internet.

For more than forty years, before his sudden death of a heart attack in March 2010, Alex Chilton touched three-plus generations of fans with his diverse musical legacy. He began his life in music in 1967 as a soulful-sounding teen idol before evolving into a brilliant songwriter and then punk provocateur in the 1970s. After a time in the wilderness—driving cabs, washing dishes, trimming trees—he became the revivified elder statesman of roots music and indie rock, from the mid-’80s until his passing. Musician Chuck Prophet wrote

of him, “

He defies categorization entirely. ENTIRELY. Isn’t that rock & roll? What rock & roll was and should be all about?”

Alex, though, was forever hell-bent on diverting attention from his artistic accomplishments and widening influence. Unimpressed with the laurels bestowed on him by music critics, alternative rockers, hipsters, and fans, Chilton carved out a sort of incognito life for himself in his adopted hometown of New Orleans.

Alex’s passing at age fifty-nine sent shock waves of grief through the music world and the international media. His death was noted on the evening news, NPR, and in more than a hundred newspapers. The

New York Times

Magazine

included him in their annual “The Lives They Lived,” in which Rob Hoerburger theorized, “

If one measure of rock stardom is being your own man, then Chilton, whose career was tracked with impurities, might have been the purest rock star of all.”

Rolling Stone

had already placed his three Big Star recordings into its 2003 list of the greatest albums of all time, and

Spin

, in its 25th anniversary issue, said Chilton “essentially invented indie and alternative rock.” In the

Los Angeles Times

, Ann Powers reflected, “

Chilton wasn’t just a genius writer of Beatles-inspired power pop songs. He was a lifelong epicurean and cultural adventurer who sought to brighten the corners of American popular music through his own work.”

Alex died the same week Big Star was to perform at Austin’s South by Southwest, the country’s largest gathering of music cognoscenti. Those who knew him, not wanting to face the hard truth, considered the possibility that he’d faked his demise to avoid the wide-eyed fandom he did not court. But just as it had during his life, his work shone despite the circumstances. Chilton pretty much stole the eighty-thousand-strong conference, with artists ranging from Ray Davies to John Hiatt, Courtney Love to Cheap Trick eulogizing him on various stages. A packed tribute concert became a cathartic, makeshift memorial for the reluctant iconoclast, a rainy parade of indie-rock luminaries. “A procession of guest musicians helped underscore both the timeless beauty of Chilton’s best songs and the wide-ranging influence his music had across different genres and generations,” reported the

Chicago Sun-Times

. More memorial concerts followed, in Memphis, New York, Los Angeles, Nashville, New Orleans, Chapel Hill, and other college towns where his trio had played small clubs off and on for twenty years. No doubt, Alex Chilton would have been bemused by all this attention, perhaps annoyed that once again his story is spun regardless of his will.

Music was Alex’s life—but what he loved more than making music was

doing it on his own terms. As former

Washington Post

writer Joe Sasfy put it, “He [was]

always riveting and real in ways few performers can ever risk. And it is those risks, in life and art, that separate Chilton from all that he has spawned.”

Falling into the music business as lead singer of the Box Tops at age sixteen, with no plan to be famous, he went on to make beautiful, sometimes harrowing music with Big Star—the group the term “cult band” personifies—and then became an iconoclastic solo artist, wandering in uncharted territory. In titling his 1995 album

A Man Called Destruction

—his last solo release filled with mostly his own songs—he acknowledged that he had often torn up the paths he’d taken before, wiping out the footprints, starting anew. As his longtime compadre Tav Falco said, “

Alex’s process was to create something that’s beautiful, then the next stage was to destroy it.” Alex continued to use his singular voice as a stylist of songcraft from all genres, while forging ahead as a guitarist, becoming an excellent, imaginative player—“the

Thelonious Monk of rhythm guitar,” according to Tom Waits.

“

All my career,” Alex said in 1993, “I’ve always kind of envied somebody like the Cramps [whom he produced], who had such a well-defined bag they were in. . . . I guess I was wishing I wanted to be that way or something. But I don’t, really, and now I don’t wish for it anymore, either.”

During the last decade of his life, in his beloved cottage in New Orleans’s Treme, he enjoyed playing a piano he bought with a check from

That ’70s Show

, which put his “In the Street” into international circulation as the series’ theme song. Alex had grown up listening to his father’s jazz on the family’s Chickering, so this simple pleasure brought him full circle. Leading an eclectic trio for nearly twenty-five years, he relished presenting an endless variety of songs—including those from his childhood and his earliest repertoire as a teenager. His longtime drummer Richard Dworkin remembers that, as they toured America together, Alex liked to find his way without using a map, driving from town to town. Though he might choose some circuitous routes, he usually found his way, pulling up to the club just in time for the gig. As in life, Alex liked traveling the byways, even if it meant getting lost sometimes. It wasn’t an easy road—but it took him where he wanted to go.