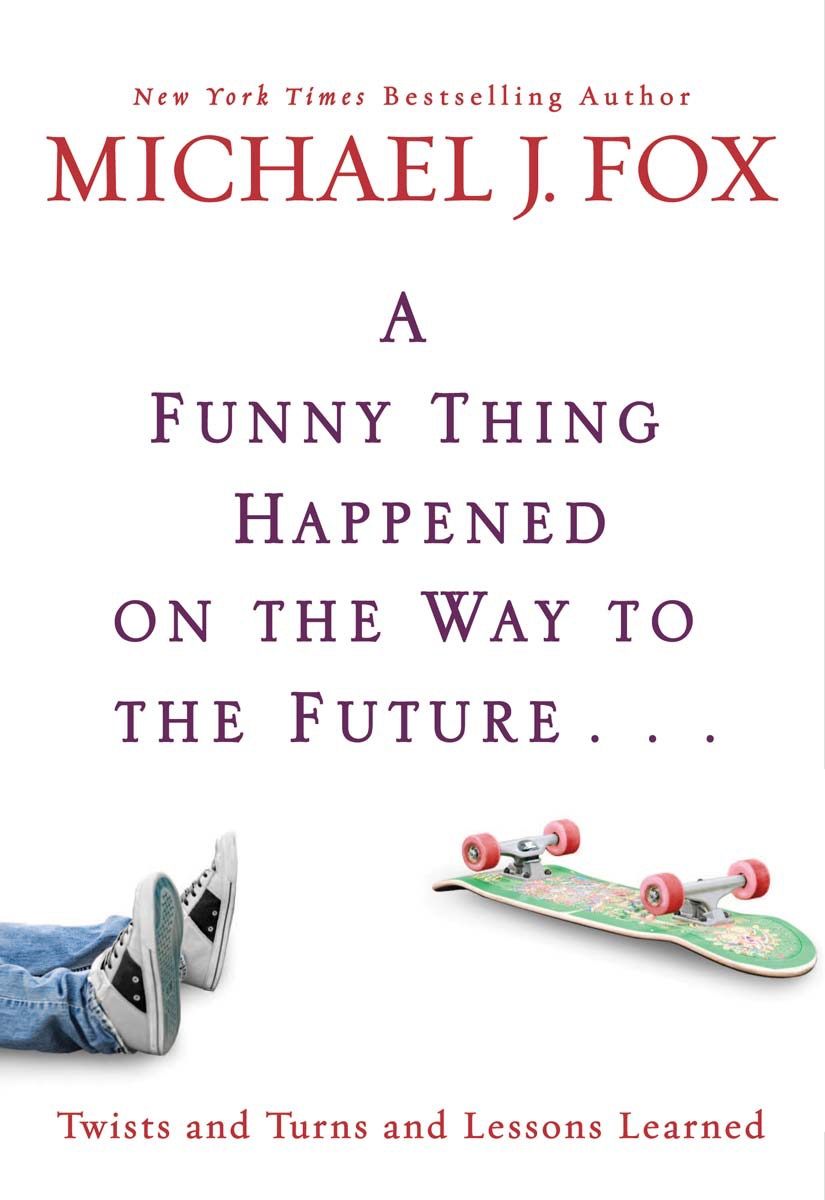

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Future: Twists and Turns and Lessons Learned

Read A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Future: Twists and Turns and Lessons Learned Online

Authors: Michael J. Fox

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Autobiography, #Actors

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Future

Twists and Turns and Lessons Learned

Michael J. Fox

For all of my teachers.

Contents

When Am I Ever Gonna Use This Stuff?

Pay Attention Kid, You Might Learn Something

MY PURPOSE IN WRITING THIS BOOK IS NOT TO OFFER

advice. Sure, I make the occasional suggestion, mostly common sense stuff. If it works, feel free to work it, though chances are you’ll figure this out on your own. If anything, this is a book that tells you that you don’t need a book. That is, you don’t need a book to tell you what you need. What I’ve done here is draw a few observations based on my life experience and organize them in response to the broader question:

What constitutes an education?

Have the last dozen-plus years prepared you for the future? Obviously, that’s impossible for you or anyone to know. I could spend five months poring over your transcript and I still wouldn’t be able to predict what the next five minutes have in store. Life is a ride. Strap in, hang on, and keep your eyes open.

A friend of mine shared this story with me. It’s a parable, origin unknown, and I found resonance in its simple truth.

A PROFESSOR STANDS

before his class with a cardboard box. From inside he produces a large, clear, empty pickle jar, and then a series of golf ball-sized rocks, which he then drops one by one into the jar until they reach the brim.

“So?” the teacher asks. “Who thinks the jar is full?” Hands shoot up, and a quick scan of the room confirms unanimity—yes, it’s full.

Next out of the box, a bag of sand, which the professor pours in amongst the rocks. Tiny grains cascade over, around, and in between the larger stones until there is no space left.

“Is it full now?” A show of hands and a chorus of voices responds—yes, it’s full.

Now the professor smiles. “But wait.” Both hands disappear into the box and reemerge simultaneously, each holding a can of beer. The crack and hiss of the pop tops are drowned out by laughter in the classroom as the amber nectar pours into the jar with the rocks and sand. Once the din of the students subsides to a collective chuckle, the professor confidently declares, “Now it’s full.”

“This jar represents your life,” he continues. “Make sure the first ingredients are the big stuff…the rocks—your family, your work, your career, your passions. The rest is just sand, minutiae. It’s in there. It may even be important. But it’s not your first priority.”

“What about the beer?” a kid in the back yells out.

“Well,” comes the answer. “After everything else, you always have room for a couple of beers with friends.”

I THOUGHT ABOUT

saving the metaphor of the jar and the stones for the conclusion of this book, but I wanted to pass it on to you as quickly as possible. You now know what it took me decades to learn. Among other things, don’t start with the beer.

Let me explain…

“I’ve never let my schooling interfere with my education.”

M

ARK

T

WAIN

MY PHOTO APPEARED ON THE MAY

23, 2008,

FRONT PAGE

of my hometown paper, the

Vancouver Sun

, but the headline identified me as “Dr. Michael J. Fox.” As neither I nor my brother, Steve, had ever given our mother any reason to expect that she’d someday utter the words “my son the doctor,” she was immensely proud that the University of British Columbia had pronounced her baby boy a “Doctor of Laws.”

Would it be crass to mention that I also have a doctorate of Fine Arts from NYU, as well as a doctorate of Humane Letters from Manhattan’s Mt. Sinai School of Medicine? They’re honorary, of course, which puts me on equal academic footing with the Scarecrow from

The Wizard of Oz

.

On that early summer afternoon in Vancouver, Canada, resplendent in my royal blue and crimson ceremonial muumuu and deftly balancing the mortarboard yarmulke atop my bobbling head, I was given the opportunity to address assembled graduates and faculty, families and friends. Just as I had done on previous occasions, when similarly honored, I opened with a question: “What the hell were you people thinking? You are aware,” I continued, “that I’m a high school dropout?”

Now that you have picked up this weighty tome from your local bookseller, I put the same question to you:

What the hell were you thinking?

Or, in the likelihood that someone else bought it for you as a graduation gift, you might want to ask them what the hell

they

were thinking. Not that I don’t have some bona fides: I did receive my GED (General Equivalency Degree). I finally put in the effort to achieve this goal at the urging of my son. He was four at the time. I’d sit at the dining room table, Sam perched on my lap playing with a plastic dinosaur, while a math tutor schooled me in the finer points of the Pythagorean theorem. And so, at the tender age of thirty-two, with my son registered to begin kindergarten the next fall, I applied to take the test that would make me, for all intents and purposes, a high school graduate.

But that was 1994, approximately fifteen years after I left high school in the eleventh grade. In the intervening decade-and-a-half, I had been alternately fortunate and unfortunate enough to receive an amazingly comprehensive education, albeit unstructured, and often unbidden. Life 101.

Some lessons, of course, are more appropriate to a certain age or stage of development. For example, my latter teenage years into my early twenties was a time when I was just smart enough to get myself into situations I was still too stupid to get out of. Later, as evidenced by Sam’s insistence that I finish what I started, I found out there is wisdom that can only come from being old enough to know how much there is to learn from children. And in the time since that milestone, I have remained a humble and grateful student of, if not the School of Hard Knocks, then at least the University of the Universal. I didn’t pick my courses; they picked me. And just as there was no formal matriculation, neither was there any graduation. There were, of course, plenty of tests.

Just to reassure you, I’m not one of those swaggering jerks who, having achieved success after dropping out of school, promotes the fiction that a higher education is a complete waste of time. All the same, I sometimes employ my lack of academic standing as a subtle goad to those who would make character judgments based solely on one’s alma mater or post-graduate degree.

As executive producer of

Spin City,

I was responsible for hiring and managing an astoundingly bright collection of young comedy writers, many of them graduates from prestigious universities: Dartmouth, Yale, Princeton, and Harvard, to name an ivy-covered few. Inspired by the irony that I was the boss of such a lettered group of individuals, and, honestly, perhaps a little intimidated, I thought I’d have some fun with it. I amassed a collection of T-shirts from some of the finest schools in the country. Among others, I had a burgundy Harvard tee and a Stanford Cardinal jersey. An old Dartmouth baseball shirt was a personal favorite. “Now,” I announced to the wunderkinds, assembled for one of our first meetings of season one, “if you see me wearing a shirt from your alma mater, say Yale, for example” (with this I’d sneak a glance at an eager young Eli whose specialty was fart jokes), “then that means it’s your day to get me coffee.” Okay, so I am capable of a modicum of swaggering jerkitude.

A scant few minutes of Wikipedic surveying will uncover an impressive roster of well-known people, in every arena of public life, who have attained success and recognition without ever having graduated from high school. Those I most relate to are, of course, the actors and entertainers, whose early life experiences were no doubt similar to my own, propelled by a common group of neuroses toward careers in show business. These include such estimable personages as Leonardo DiCaprio, Johnny Depp, Robert De Niro, Chris Rock, Kevin Bacon, John Travolta, Hilary Swank, Jim Carrey, Charlie Sheen, Sean Connery, Al Pacino, and Quentin Tarantino.

But it’s not just actors who have achieved success despite bailing on their formal education. Here’s a group, sure to be a corkscrew to the gut of any CPA with an MBA, that includes some of the more impressive dropout

billionaires

: Richard Branson (founder of Virgin Music and Virgin Atlantic Airways); Andrew Carnegie (industrialist); Henry Ford (founder of the Ford Motor Company); John D. Rockefeller (oilman); Philip Emeagwali (supercomputer scientist and one of the pioneers of the Internet); Kirk Kerkorian (investor and casino operator); and Jack Kent Cooke (media mogul and owner of the Washington Redskins).

And my favorite list:

geniuses

without diplomas, including Thomas Edison, Albert Einstein, and Benjamin Franklin.

To be fair, there isn’t enough paper in the world to print a

Who’s Who of Famous Persons Who Actually Finished High School.

And an argument can be made, I’m sure, that successful dropouts are even rarer in an increasingly competitive modern job market where degrees, diplomas, and technical knowledge carry more weight than ever. There are plenty of old-timers on these lists, for sure, but it more than makes the case that one can be smart without necessarily being “book smart.” Just as the reverse is true. As Dan Quayle once held, “What a waste it is to lose one’s mind. Or not to have a mind is being very wasteful. How true that is.” Dan went to DePauw University and received his law degree from the University of Indiana. Oh, and he put in four years as the second most powerful man on the planet.

Still, there really is no substitute for a solid education to inform a maturing mind. The men and women on these lists may have prospered, not through avoidance of a classic education, but by finding a way, if not to replicate it, then to approximate it. Whether you go to school or set out on your own, certain lessons are unavoidable. Speaking from personal experience, it might be less painful to learn them in the classroom.

When Am I Ever Gonna Use This Stuff?

AS FOR MY OWN TRUNCATED SECONDARY EDUCATION,

my head was in the clouds as my mom would say, or if you asked my father, up my ass.

In the outright creative subjects (drama, music, creative writing, other art electives, drawing, painting, and printmaking) I’d bring home A’s. But any subject based on fixed rules, like math or chemistry or physics, sent my grades into free fall; the gold stars and smiley faces from grade school were long gone.

At report card time, I’d try to explain to my exasperated mother: “These are absolutes, Mom. They’re boring. Take math, two plus two equals four. I mean, that’s already on the books, right? Somebody’s already nailed that down. What do they need me for? If someone’s got a handle on how to get it to add up to five, count me in.” Mom would sigh and hurry to sign the report card before Dad got home.

When red flags began to pop up on the school front, blue veins would pop up on Dad’s forehead. A barely passing grade, or a call from school about a trip to the principal’s office, prompted a harsh reprimand from Dad, followed by a probative grilling as to what the hell I was thinking and demands that I get my “ducks in a row forthwith.” I wasn’t failing out of rebellion though; I wasn’t angry at my parents, or anybody else. Yet throughout junior high, my academic grades continued to plummet. The reprisals from Dad, once automatic, tapered off as he accepted their futility. He’d curl his lip, throw up his hands, and stalk off—that is, if I didn’t slink off first.

By the time I entered high school, I had forsaken academics altogether in favor of my burgeoning acting career. An aptitude had become a passion and flowered into a dream. During much of the fall of 1978, I was going to school by day and performing at night in a long-running hit play at the Vancouver Arts Club, the big Equity theater company in town. I’d work at the theater until well after midnight every night, climb out of bed in the morning, go through the I’m-off-to-class motions, scramble into my pickup truck, proceed to the nearest park, pull under the cool shade of a maple tree, fish a foam pad out of the cab, slap it down in the bed of the truck, and go back to sleep.

My first class in the morning was drama, and I found myself in the strange position of receiving solid reviews for my professional acting at the same time I was flunking high school drama for too many absences. I pointed this irony out to my drama teacher, angling for credit for work experience. No soap. Truth is, her hands were tied by administrative policy.

Over time, it became clear that I was flunking just about every class I had. I gave notice that I would not be returning for classes in the spring. I made the rounds at school, cleaned out my locker, and said good-bye to friends and those teachers with whom I was still on speaking terms. Doubt about the wisdom of my decision was nearly unanimous. I remember one exchange, in particular, with a social studies teacher. “You’re making a big mistake, Fox,” he warned. “You’re not going to be cute forever.” I thought about this for a beat, shot him a smile, and replied, “Maybe just long enough, sir. Maybe just long enough.”

My dad agreed to drive me down to Los Angeles to find an agent and begin to build a career. You might have expected him to protest, but having only stayed in school through eighth grade himself, he reasoned that although I was a screw-up in school, I was already making a decent wage as an actor. Of the move to California, he said, “Hey, if you’re going to be a lumberjack, you’d better go to the forest.”

Whoa

, you the high school or college grad might be thinking right now.

That’s a helluva lot different from my experience.

I don’t know…is it? As I reflect on it now, it seems fairly representative of the rite of passage that millions of seventeen-and eighteen-year-olds go through every year. My leaving home was analogous to the experience of any fledgling college student. I gave myself four years to achieve my goal of becoming a steadily working actor, and what’s more, I had a leg up on many of my peers heading off to State U. in that I already had my major, recognizing of course that it was not one offered by my erstwhile high school.

So my dad drove me to L.A. just like your parents likely drove you to Kenyon or Ball State, or whichever school of your choosing chose to have you. And the next four years provided as intense an undergraduate experience as one would expect from any college career, replete with parties and heavy workloads, not enough spare time, too much spare time, parties, deadlines, successes, failures, parties, heartaches, girlfriends, parties, ex-girlfriends, future girlfriends, parties, and a graduation of sorts. Was I nervous at first? Were you? Me neither, not really. I was pumped. I knew this was the next step for me, although one of the reasons it might have been so easy to make up my mind was that my brain, like the brain of any eighteen-year-old, was still under construction (trust me, I know from brains).

Teenagers blithely skip off to uncertain futures, while their parents sit weeping curbside in the Volvo, because the adolescent brain isn’t yet formed enough to recognize and evaluate risk. That’s why we can talk young men and women into fighting wars, and MTV and ESPN 2 are crowded with tattooed mohawk-wearers leaping buses on skateboards. The prefrontal cortex, sometimes known as the seat of reason, is the part of the brain that we use to make decisions. It’s our bulwark against banzai behavior. A teenager’s prefrontal cortex is still growing, still connecting up with other parts of the brain. It’s the

amygdala,

home base for gut reactions and raw emotion, that’s going full blast at this point. Not a lot of reasoned thinking going on there.

With so many immediate considerations to deal with, I don’t know if my parents had time to ponder the broader implications of the odyssey I was embarking upon. As removed as they were from the world of showbiz, they might not have been informed enough to have specific fears, but they were still visited by worries that I could very well be sucked into a whirling vortex of depravity, exposed to a nonstop bacchanalia—a moveable feast of drunkenness, disorderly conduct, and brazen sexuality.

Sure, all that happened, but the party, it turned out, wasn’t in Hollywood, but Westwood, the campus of UCLA. While I had no connection to the academic life at the university, I had become friends with three transfer students from the University of Maine, frat brothers who were living off campus while waiting for space to open up at the fraternity house. Temporarily occupying the apartment next to mine, the Maine-iacs (as I referred to them) were dealing with Orono-to-L.A. culture shock every bit as jarring for them as my own Canada-to-California adjustment. It was easy to recognize aspects of my own experience in theirs. Young, far from home, hoping to measure up to some still undefined standard, they studied their textbooks in pursuit of better grades, just as I pored over scripts in pursuit of better jobs.

Although we went our separate ways during work and school hours, my friends provided me with an entree into what were easily the best parts of life on campus—free beer and college girls. I remember thinking at the time that our situations were similar, but I allowed myself extra points for the pressure that came with trying to find the next job. “You’ve got it easy,” I’d tell them. “Your parents bought you four more years of high school.”

This was wrongheaded on a number of levels. For starters, college is a lot more demanding than high school—not that the demands of high school were all that familiar to me, given that I had made little effort to meet them. The other flaw in my pronouncement was that it made an easy assumption about who was footing the bill. My perception, rooted in my Canadian working-class background, was that behind each of these partying coeds were a beneficent and indulging American mom and pop, happily forking over cash to the university, who in turn would feed and water the kid for however long it took for the prefrontal cortex and amygdala to assume their proper weights in the balance of influence.

Floating my “four more years of high school” theory would provoke an earful in response. Did I have any idea what kinds of loans these guys were carrying? I had to admit, I didn’t. Much of the expense of their formal education was front-loaded, whereas with my experiential education, I was, in effect, running a tab; especially dangerous, as I’ll point out shortly, when you can’t do basic math. So, we all felt the weight of expectation. Still, I felt more comfortable not to be carrying all that debt before I had even decided what was worth going into debt for.

Despite being an indifferent high school student, I always enjoyed reading, and was familiar with the story of Sisyphus. I pictured the Maine-iacs, with their student loans, as each having to push a large rock up a mountain. I began to understand that the rock was not the debt, but their course load. The debt was the mountain. Me, I was just dancing on the edge of a cliff.

So each of us, whether they off to college or me off to Hollywood, could be described as full of bluster and bravado, high expectations and low reservations. What separated us, perhaps, was that I lacked a blueprint.

As an exercise, I recently picked up a course catalogue from Hunter College, part of the City University of New York. Reading through the curriculum, I recognized how my life experiences could fit into a prescribed outline for an undergraduate education: the one I had supposedly missed out on. Laying out a series of typical college courses, as described in the catalogue, can help make a case that I have, to some extent, fulfilled the requirements for each particular course while having absolutely no idea I was doing it.

I might have skipped class, but I didn’t miss any lessons.