A Dinner to Die For (27 page)

“What about Yankowski?”

“Yankowski had never seen Mitch go into a rage; he might have suspected Mitch would be angry if he saw Earth Man and was reminded of Yankowski’s little victory, but he couldn’t have guessed Mitch would fly into a rage, turn purple, and end up with his sinuses blocked. No one in the kitchen had seen Mitch react to Earth Man, because Laura made a point of having Earth Man come at eleven, an hour before Adrienne allowed Mitch in the kitchen.”

Howard poured the wine, and stood, still holding the bottle. “I wouldn’t say this to just anybody, Jill, but from everyone’s description of her, it’s hard to picture Laura Biekma deciding on a death sentence, much less carrying it out. She was the peacemaker, right? The one they all depended on.”

“But they counted on her because she

could

make decisions. They all thought of her making choices in their favor; what they forgot or never bothered to recognize was that those decisions often went against someone else. Rue was sure Laura would agree she needed quiet. If that meant that the owners of Paradise would lose money, she didn’t think about it. These people saw in Laura what they wanted to see. They forgot that she was the one who canceled orders, who made the decision to fire people. She handled complaints at the water company. She was used to dealing with bad situations and making decisions.”

“Still, it’s a shame.”

I nodded.

“Laura will get a lot of sympathy. She’ll make an appealing defendant. The DA’s going to be on your back till her trial’s over. I’ll tell you, Jill, no matter how clear the evidence is, that’s one prosecution I wouldn’t touch.”

“Me either. But knowing that is kind of a relief.” I smiled, not just at relief for Laura, but at my own. Laura had been in the ambulance before it occurred to me that I had driven down the hill. But this time there had been no pavement to contemplate, no music to listen to; there had been only the driving. No way to avoid it.

When I stopped I was covered with sweat, as usual, but I wasn’t shaking as I had been when I drove down Marin those three times. And I knew then that the next time I drove downhill I would be sweating, I would be afraid, but it wouldn’t be quite so bad. I had faced the fear full on. I wouldn’t be afraid of being afraid again. It might be months before I drove downhill calmly, but I would do it.

“You want anything to eat?” I asked.

He hesitated, then shook his head, ordinarily a very un-Howardian response.

I poured the wine and handed him a glass. He let his fingers rest on mine a moment longer than necessary.

“What did Doyle say?” he asked. “Did he redeem himself with you?”

“He didn’t think I was too weak to make it in by quarter to eight tomorrow morning.”

“Well, Jill, it’s tough to be tough.” Howard grinned and held his glass up to toast that thought. “That all he said?”

“Oh, no.” I put the bottle down.

“Well?”

“ ‘Smith,’ he said, ‘a chase like that, you could have been killed.’ ”

Howard nodded. He was still wearing that striped rugby shirt. It hung loosely off his sinewy shoulders. He had a slender, well-defined chest.

“Doyle?” he prompted.

“Oh.” I took a sip of wine. “Well. He said I could have been killed. And if I had been, we’d have no case because I haven’t done the paperwork.”

Howard laughed.

I drank some of the wine.

He leaned back against the counter.

Suddenly, I was aware of the silence, a silence unlike any of those in the four years we had been friends. The Tibetan Buddhists talk about pockets in time. I doubted this was exactly what they meant. Maybe this wasn’t a pocket, but time was moving so slowly it was as if I could hear each second tick off. I put down my glass. Howard reached behind him, fumbled for the edge of the counter, and slid his glass on the counter. Our hands met, and for what seemed a very long time I felt the warmth of his flesh, the thick mounds at the base of his fingers, the hollow of his palm, the tension throbbing right below the skin. I reached out between those long thin fingers, and felt the pressure and the restraint as they clasped in around my hand.

Together we leaned forward, letting the touch of our bodies come slowly, savoring each new sensation. It was Sunday; we had the whole day.

With special thanks to Inspector Stan Muller of the Berkeley Homicide Detail and Officer Karan Alveraz of the Albany Police Department for their help and patience in answering my questions.

Susan Dunlap (b. 1943) is the author of more than twenty mystery novels and a founding member of Sisters in Crime, an organization that promotes women in the field of crime writing.

Born in New York City, Dunlap entered Bucknell University as a math major, but quickly switched to English. After earning a master’s degree in education from the University of North Carolina, she taught junior high before becoming a social worker. Her jobs took her all over the country, from Baltimore to New York and finally to Northern California, where many of her novels take place.

One night, while reading an Agatha Christie novel, Dunlap told her husband that she thought she could write mysteries. When he asked her to prove it, she accepted the challenge. Dunlap wrote in her spare time, completing six manuscripts before selling her first book,

Karma

(1981), which began a ten-book series about brash Berkeley cop Jill Smith.

After selling her second novel, Dunlap quit her job to write fulltime. While penning the Jill Smith mysteries, she also wrote three novels about utility-meter-reading amateur sleuth Vejay Haskell. In 1989, she published

Pious Deception

, the first in a series starring former medical examiner Kiernan O’Shaughnessy. To research the O’Shaughnessy and Smith series, Dunlap rode along with police officers, attended autopsies, and spent ten weeks studying the daily operations of the Berkeley Police Department.

Dunlap concluded the Smith series with

Cop Out

(1997). In 2006 she published

A Single Eye

, her first mystery featuring Darcy Lott, a Zen Buddhist stuntwoman. Her most recent novel is

No Footprints

(2012), the fifth in the Darcy Lott series.

In addition to writing, Dunlap has taught yoga and worked for a private investigator on death penalty defense cases and as a paralegal. In 1986, she helped found Sisters in Crime, an organization that supports women in the field of mystery writing. She lives and writes near San Francisco.

Dunlap and her father at the beach, probably Coney Island. ”“My happiest vacations were at the beach,” says Dunlap, “here, at the Jersey shore, at Jones Beach, and two glorious winter weeks in Florida.”

Dunlap’s grammar school graduation from Stewart School on Long Island, New York.

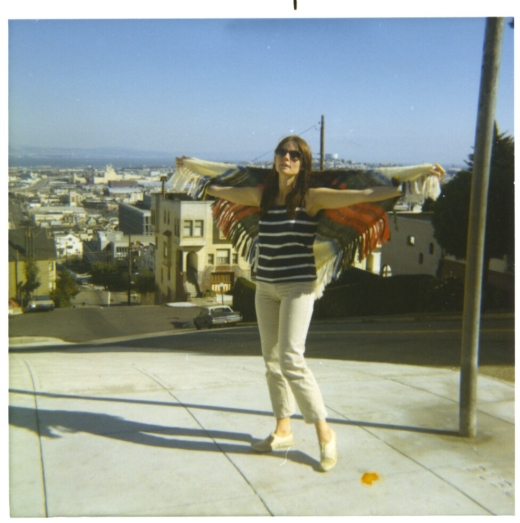

In 1968, Dunlap arrived in San Francisco; this photo was taken by her husband-to-be atop one of the city’s many hills. Dunlap recalls, “It’s winter; I’m wearing a T-shirt; I’m ecstatic!”

Dunlap’s dog Seumas at eight weeks old. “We’d had him two weeks and he was already in charge, happily biting my hand (see my grimace),” she says. “He lived for sixteen good, well-tended years.”

Dunlap started practicing yoga in 1969 and received her instructor certification in 1981, after a three-week intensive course in India with B. K. S. Iyengar. Here she demonstrates the

uttanasa

pose (the basic standing forward bend) for her students.

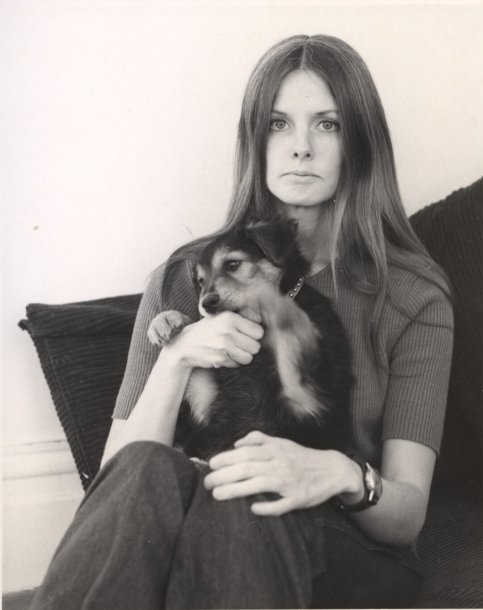

Seumas and Dunlap in 1988: “He was an old guy by this time, who had better things to do than be a photo prop. I think his expression says it all.”

Dunlap relished West Coast life. “This is what someone who grew up in the snow of the East Coast dreams of . . . the California life!”