A Dark Anatomy (32 page)

Authors: Robin Blake

Â

Â

M

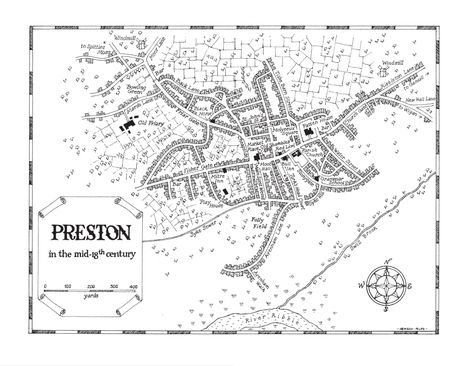

ID-GEORGIAN PRESTON, where this story is set, was one of England's ancient self-governing charter towns. By the 1600s it had grown into the prime social and legal centre of Lancashire, being pleasantly and strategically located in the heart of the county, with a busy agricultural market, and a significant community of craft workers amongst its stable population of about 5,000. It remained like this until the end of the century when industrialization transformed the town into the grimy, overcrowded manufactory that Charles Dickens called Coketown, his setting for Hard Times.

ID-GEORGIAN PRESTON, where this story is set, was one of England's ancient self-governing charter towns. By the 1600s it had grown into the prime social and legal centre of Lancashire, being pleasantly and strategically located in the heart of the county, with a busy agricultural market, and a significant community of craft workers amongst its stable population of about 5,000. It remained like this until the end of the century when industrialization transformed the town into the grimy, overcrowded manufactory that Charles Dickens called Coketown, his setting for Hard Times.

Today hardly anything pre-Victorian remains except the central medieval street-plan: the three principal streets of Church Gate, Fisher Gate and Friar Gate, leading east, west and north-west from the focal point of the flagged marketplace and the site of the medieval Moot Hall. This building collapsed in 1780 to be succeeded by three further civic structures, the latest a 1960s office block of remarkable ugliness. So, to conjure up the pre-industrial scene, you have to vault back from today's ring-roads, pre-stressed concrete and glass, over sooty Victorian stonework and uniform red-brick back-to-backs, to imagine a vanished townscape mixing medieval, Tudor and Georgian styles.

Administratively eighteenth-century Preston was, like most other borough towns, an oligarchy. The council's twenty-four members (or burgesses) appointed each other and parcelled out the senior offices, including that of the Mayor and two bailiffs, annually between themselves. Charter towns like this were virtual city-states where (in Tom Paine's scathing words) a man's ârights are circumscribed to the town and, in some cases, to the parish of his birth; and all other parts, though in his native land, are to him as a foreign country'. These communities reserved the right to run their own affairs, and keep âforeigners' away at all costs.

I have taken liberties with a few local details, not least in the coroner's own office. In historical Preston the unusual custom was for the annually appointed Mayor to sit as coroner

ex officio

. But, preferring him to stand apart from local politics, I impose the more typical English model whereby Titus Cragg is directly appointed by the crown, with life-tenure. My other inventions include Garlick Hall, the nearby village of Yolland, and most of the cast of characters.

ex officio

. But, preferring him to stand apart from local politics, I impose the more typical English model whereby Titus Cragg is directly appointed by the crown, with life-tenure. My other inventions include Garlick Hall, the nearby village of Yolland, and most of the cast of characters.

âMr Spectator', one of Cragg's heroes, is the imaginary writer of the London periodical

The Spectator

, written in the reign of Queen Anne (March 1711 â December 1712 and June â November 1714) largely by Sir Richard Steele and Joseph Addison. Cragg also reveres âMr Isaac Bickerstaff', the persona behind Steele's earlier

Tatler

, which appeared in 1709. These single-sheet papers had a character very like today's Internet blogs: they appeared several times a week to ruminate on public issues as they cropped up. Both

Tatler

and

Spectator

were then collected in book form and their contents remained hugely popular as arbiters of taste and good sense throughout the Georgian age.

The Spectator

, written in the reign of Queen Anne (March 1711 â December 1712 and June â November 1714) largely by Sir Richard Steele and Joseph Addison. Cragg also reveres âMr Isaac Bickerstaff', the persona behind Steele's earlier

Tatler

, which appeared in 1709. These single-sheet papers had a character very like today's Internet blogs: they appeared several times a week to ruminate on public issues as they cropped up. Both

Tatler

and

Spectator

were then collected in book form and their contents remained hugely popular as arbiters of taste and good sense throughout the Georgian age.

By Robin Blake

Â

A Cragg & Fidelis Mystery

Â

Â

Â

PRESTON, 1741

Â

The drowning of drunken publican Antony Egan is no surprise â even if it comes as an unpleasant shock to coroner Titus Cragg, whose wife was the old man's niece. But he does his duty to the letter, and the inquest's verdict is accidental death. Meanwhile the town is agog with rumour and faction, as the General Election is only a week away and the two local seats are to be contested by four rival candidates.

But Cragg's close friend, Dr Luke Fidelis, finds evidence to cast doubt on the events leading to Egan's demise. Soon suspicions are further roused when a well-to-do farmer collapses and it appears he was in town on political business. Is there a conspiracy afoot? The Mayor and Council have their own way of imposing order, but Cragg is determined not to be swayed by pressure. With the help of Fidelis's scientific ingenuity the true criminals are brought to light â¦

An extract of the gripping sequel to

A Dark Anatomy

follows here.

A Dark Anatomy

follows here.

Chapter One

Â

Â

A

HUMAN BODY IN the salmon traps was not such a rare event. The one they caught in the spring of 1741 was the fifth during my eight years as coroner in the borough of Preston. On the other hand, from my point of view, there was something very particular and personal about the latest one. This corpse was my kith, if not quite my kin.

HUMAN BODY IN the salmon traps was not such a rare event. The one they caught in the spring of 1741 was the fifth during my eight years as coroner in the borough of Preston. On the other hand, from my point of view, there was something very particular and personal about the latest one. This corpse was my kith, if not quite my kin.

But I had no idea of that when the call to the riverbank came early on that Monday morning, exactly seven days before we were due to begin a week of voting in that year's General Election. I immediately hurried out to perform the coroner's first duty â that of answering the summons to a questionable death, and judging the need for an inquest. On my way to the stretch of the River Ribble in which the traps were laid, I naturally had to pass along Fisher Gate, where my friend Luke Fidelis lived on the upper floor of the premises of Adam Lorris, the bookbinder. Reaching Lorris's address, I mounted the steps to the door and pealed the bell. If Fidelis was at home he could be of some use to me. When bodies were found floating in the river, the initial questions were always the same: How long had they been there? How far had they travelled? Doctor Fidelis's knowledge of physiology, and such things as the progressive effects of total water immersion on a corpse, was far ahead of mine.

Mrs Lorris went up to tell Fidelis I had called and of course, as was his habit, my friend was still lounging in bed. I chatted for a few minutes at the foot of the stairs with Lorris and Mrs Lorris. He told me of his progress with my old childhood book of

Aesop's Fables

that I had brought to him for rebinding.

Aesop's Fables

that I had brought to him for rebinding.

âI read the book through with Mrs Lorris before I started, and we were vastly entertained, were we not, my heart?'

âOh yes, Mr Cragg!' Dot Lorris exclaimed, her face breaking into creases of remembered enjoyment. âSuch tricks those animals got up to.'

âYes, Mr Aesop was a clever fellow,' I agreed. âHe had a charming way of translating human nature into the behaviour of beasts.'

I glanced up the stairs for a sign that Fidelis might be stirring himself. There was none.

âThere's some of the fables, mind, that a husband would do better not to put before his wife,' observed Lorris.

âOh? And which are those, Husband?' Dot challenged.

â

The Fox and the Vixen

for one. Remember it, Mr Cragg?'

The Fox and the Vixen

for one. Remember it, Mr Cragg?'

I said I had a vague memory of it.

âThat vixen,' said Lorris, shaking his head, âshe stayed under cover and let the fox run from the farmer by himself. There's little wifely love in that, or trust.'

âTrust!' laughed his wife. âWhat was there to trust? He calculated that if both of them ran, his wife would be caught and he would get away. The farmer could only chase after one of them, and that would be the vixen, as she was the slower.'

âNo,

she

calculated that if she stayed under cover, she'd save herself and damn the fox.'

she

calculated that if she stayed under cover, she'd save herself and damn the fox.'

âThe fox damned himself when he lost his nerve,' was Dot Lorris's pitiless rejoinder.

Before the discussion grew too heated I steered it towards

the election. The people of Preston were excited at having a contested vote at last. In the previous parliament, and the two before that, our borough members had simply walked-over, as no one could be found to stand against them. This time four men would be fighting over the two seats, making for a much livelier prospect.

the election. The people of Preston were excited at having a contested vote at last. In the previous parliament, and the two before that, our borough members had simply walked-over, as no one could be found to stand against them. This time four men would be fighting over the two seats, making for a much livelier prospect.

After a couple of minutes we heard Fidelis's voice calling down.

âCragg, I'm in my nightshirt, but come up if you like.'

Instead I called up to him.

âGet dressed, Luke. It's almost seven and I'm taking you for a walk by the river.'

âA walk? Before

seven

? Surely it can wait.'

seven

? Surely it can wait.'

âNo. It is now or not at all.'

At length, the tall, fair-haired figure of Preston's youngest and most adventurous doctor appeared on the stair. He was grumbling, as usual, when asked to do a thing before eight in the morning.

âI only wanted half an hour more of sleep, Titus,' he growled. âI was drinking until past midnight.'

In consideration of Luke's aching head I did not set too sharp a pace as we went along Fisher Gate and then, by a turning to the left, into the lane that passed the playhouse and headed down from the bluff, along which the town is ranged towards the riverbank.

âWell, what is it?' Luke asked. âI don't suppose this outing is for the improvement of my health.'

âNo. There's a body in the river.'

âAh!'

We walked on in silence to the bottom of the steep path, before striking across the meadow beside the riverbank. But I sensed an increased spring in Luke's step. He was stimulated by

the opportunity to assist me in my inquiries; more so, I think, than I was in leading them.

the opportunity to assist me in my inquiries; more so, I think, than I was in leading them.

Â

In many towns, the river is a high street. The buildings line up expectantly alongside it, waiting for trade to come across its wharves and quays, while locks upstream and down regulate the water for the traffic of lighters and barges. None of this is so at Preston, for the river is at a distance, and on a different level. Abreast of the town to the south, it is at this point wide and, being close to the estuary, tidal. But it drains a great area of uplands to the east and, after heavy or prolonged rains combined with a tide, it can go so high that the water meadows flood up to a hundred yards on either side. To keep its skirts dry, therefore, the town stays aloof on its ridge, a quarter mile distant from the waterside, and it is possible to live one's life there without any particular consciousness of the river, except as a barrier to be crossed when travelling south, and as the regular provider of fish suppers.

On this morning, breezy after yesterday's downpour, the current was big and tumbling, but it had stayed within the banks. A group of men wearing knee-length boots of greased leather were working the traps from boats that bobbed and pitched in the boiling stream. They were gaffing the last of the fish that had come into the traps during the night, and bringing them ashore to add to the neat row of those already landed. As we came near enough to see the display of salmon, like spears of bright polished pewter in the riverbank grass, we saw a gaggle of women in bonnets and full-length cloaks, advancing along the bank towards us, laughing and singing. It would be their job to pack the fish in rush parcels and carry them up to the market.

The women arrived at the same time as we did, and

immediately their laughter died as they saw the thing lying, stretched companionably alongside the row of fish, as if it was itself an enormous example of the species. It was wrapped in a net like a parcel, but this did not fully conceal the fearful truth: the head end was rounded, from which the shape swelled smoothly up to the belly in a small mound before tapering away again. At the end where â had it really been a monster salmon â the tail should be, two splayed feet protruded. They wore the wooden-soled clogs of the countryman, strengthened like a horse's hoof with curves of steel nailed into them.

immediately their laughter died as they saw the thing lying, stretched companionably alongside the row of fish, as if it was itself an enormous example of the species. It was wrapped in a net like a parcel, but this did not fully conceal the fearful truth: the head end was rounded, from which the shape swelled smoothly up to the belly in a small mound before tapering away again. At the end where â had it really been a monster salmon â the tail should be, two splayed feet protruded. They wore the wooden-soled clogs of the countryman, strengthened like a horse's hoof with curves of steel nailed into them.

The sight provoked immediate cries of dismay from the women.

âQuiet yourselves,' shouted one of the men, as he carried the last of the fish up from his boat and slapped it down with the others. âCoroner's here. You should be respectful.'

I asked who was in charge of the fishing party. It was the man that had just spoken, whose name was Peter Crane.

âWas it you that first saw it in the water?' I asked.

âIt was. Me and the lad spotted it first.'

Crane nodded towards a youth who looked a younger edition of himself.

âWhat time was that?'

âAn hour ago, or a bit more.'

I took out my watch. It was half past seven.

âBefore half past six, then.'

âIf you say so.'

âAnd did you find him just like that?'

âHow do you mean?'

âWrapped in the net.'

âOh no. We wrapped him when we brought him ashore, like. Out of respect.'

Or

, I thought

, to stop him getting up and running away

.

It was a common thought: you can never be too sure of those that drown.

, I thought

, to stop him getting up and running away

.

It was a common thought: you can never be too sure of those that drown.

âWould you kindly uncover him for me now?'

It took three men to undo the parcel, so heavy was the body, and so well-wrapped.

âDid you know him?' I asked as they struggled.

âOh, aye, we knew him.'

âWho was he?'

âDon't think you won't know him yourself, Mr Cragg. Take a look.'

Finally, with two of them pulling his feet and a third at the other end hauling the net, they had managed to disencumber the body. The dead man was wearing a coat, shirt, breeches and the aforementioned clogs. His grey hair was tied at the back. His eyes were closed.

âGood God!' exclaimed Fidelis. âLook who it is.'

We all drew closer, and there was a murmur of recognition from the women. I knew the man better even than the others and, for a moment, was so disconcerted I could not speak. Not only did I well know his identity, I knew also that the contented impression conveyed by the corpse was false. For these were the mortal remains of poor Antony Egan, landlord of the Ferry Inn and the sadly troubled uncle of Elizabeth, my own sweet wife.

âDid you close the eyes, or were they like this when you found him?' Fidelis asked Crane.

âNo, Doctor, staring open they were. I closed them.'

As a simulacrum of sleep it made the man look at peace, an appearance reinforced by the hands being arranged comfortably over the swollen stomach.

I knelt down on one knee beside him, opened his sodden coat and went through the pockets. They were empty except for a tobacco pouch, a few coppers and his watch, its chain securely

attached to a waistcoat buttonhole. Then I stood again and looked at Fidelis who was on the other side of the corpse.

attached to a waistcoat buttonhole. Then I stood again and looked at Fidelis who was on the other side of the corpse.

âHe has his watch,' I said.

âHe wasn't robbed, then.'

âWhen do you think he went into the water?'

âI doubt it was long ago.'

âDid he drown?'

âLet's see. Mr Crane would you and your men kindly turn him over for me, and bring him round so his head's over the river.'

The dead man was placed, according to Luke's instructions, on his stomach with head and shoulders over the stream and arms trailing in the water â the posture of one who throws himself down to drink, or a boy attempting to tickle a trout. Luke then crouched beside him and placed both hands palms down, with fingers spread out, flat on his back.

âLook at the mouth, Titus, while I palpitate.'

I placed myself on the other side of the body and sank down on one knee, leaning a little over the water to see the profile of Antony's head. Luke pressed his hands down sharply three or four times in a kneading motion just below the rib cage and immediately water gushed up and out of the mouth, like water from a parish pump. Luke stood up.

âYou saw it?' he asked. âLungs full of water. He sucked it in trying to breathe. It means he was alive when he went into the river. He died by drowning.'

I rose from my genuflection and considered for a moment. The cloud cover was disintegrating and patches of freshly minted blue sky had opened up over our heads. Then, in the east, the morning sun broke free and shafts of light set the swollen river surface glittering.

âWell, Luke, I have a ten-minute walk upstream ahead of

me. It's a fine day. Will you come along, or have you other business?'

me. It's a fine day. Will you come along, or have you other business?'

He said he had no patients to see immediately and would be glad to go with me. I asked Crane to get some sort of conveyance, and use it to transport Egan's body along the bankside path behind us.

âThere will be an inquest but I see no reason why he can't lie at home, and be viewed there by the jury. There've been inquests at the Ferry Inn before. It's better that I go ahead, to break the news to his daughters. They will need time to prepare.'

Luke and I set off at a brisk pace to walk to the inn. It stood half a mile above the salmon traps, rather less than midway to the big stone bridge at Walton-le-Dale that bears the southern road for Wigan and Manchester. A road of sorts branched from there to connect with the ferry-stage, and for uncounted centuries traffic from the south had been transported across the stream in competition with the bridge. The Ferry Inn, lying on the southern bank, had served the needs of those waiting to cross, and a good business it had been, for the reason (which was really unreason) that, while a ferry crossing was cheaper than the bridge toll, many of those waiting to use it were happy to spend the saved money on drinking, eating, card-playing and, sometimes, a bed for the night. So business had come to the inn as naturally as fish got into the salmon traps.

Other books

A WILDer Kind of Love by Angel Payne

Come Share My Love by Carrie Macon

Tension by R. L. Griffin

Wild Child by M Leighton

A Pledge of Silence by Solomon, Flora J.

Dame la mano by Charlotte Link

Down in the City by Elizabeth Harrower

Honourable Schoolboy by John le Carre

The Village of Dead Souls: A Zombie Novel by Michael Wallace