1989 (28 page)

Authors: Peter Millar

An urbane, sophisticated, cultured and highly intelligent man, the reason I was interviewing him in 1997 was that he had just

published

his first cookbook: a highly readable nostalgic collection of Russian recipes and childhood reminiscences. There was something more than slightly surreal about sitting at one of the new pavement cafés outside the redbrick

Rotes Rathaus

, now once again City Hall for reunited Berlin, chatting to a man credited with being the Soviet bloc’s most successful spymaster. It was Wolf who had infiltrated one of his own agents into the heart of the Bonn government, a coup which when belatedly discovered led to the fall of Chancellor Willy Brandt’s government. He chose to regale me with far more entertaining stories, notably about how difficult it was to organise security when Fidel Castro paid a state visit to East Berlin, because instead of sticking to his schedule and keeping within sight of his Stasi-appointed bodyguards the Cuban dictator lived up to his

reputation

by climbing out of hotel room windows to visit whorehouses. Before we parted I had the chance, however, to pull a surprise on Wolf: I produced from my bag the thick lever-arch bound copy of my Stasi file and asked him to comment. He looked uncomfortable for a bit, then shrugged and said that after all, his responsibility had been gathering foreign intelligence, not domestic surveillance. But he signed it for me, anyhow, adding the comment: ‘As a bit of fun.’

But as he knew, as I know, as anyone who ever lived in a totalitarian

society will testify, a state that practises constant surveillance of its citizens is no laughing matter. George Orwell, whose

mould-breaking

novel

1984

was published sixty years ago this year, gave us

neologisms

that are not only still with us, but expand their resonance year on year: doublethink, newspeak, Room 101, and above all, Big Brother. Orwell described a world in which three competing alliances – Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia – are forever at war with one another, a war which necessitates their near-total control over their own citizens’ lives; a war of which occasionally maverick citizens doubt the necessity – or reality – but which is convenient for the authorities who rule over them.

Orwell may not have got it exactly right – the power blocs of today may not be absolutely identical in number or geography – but he came a lot closer than is comfortable. His concept of Britain

redesignated

‘Airstrip One’, an unsinkable aircraft carrier and

unquestioning

ally of an American-based power bloc, appeared horribly near the knuckle during the uncomfortable unequal alliance entered into by former prime minister Tony Blair with US president George Bush. For decades we were told that the Cold War was a standoff that threatened humanity, that the clock stood at five minutes to midnight. Life seemed perpetually under threat. Having grown up in Northern Ireland and used to the perennial IRA threat, to being forever on the lookout for suspect packages, to being searched going into shops, the respite after the Good Friday agreement seemed wonderful. Yet no sooner had both decades-old threats been lifted than along came the ‘clash of civilisations’ and the ‘war on terror’ to take their place. Our politicians abhor a vacuum of terror. A climate of fear gives them a greater mandate over the lives of their citizens.

What could be more Orwellian an example of doublethink and newspeak than the daily announcement on the London Underground that it is ‘important to be watchful at all times during this period of heightened security’? What they mean is ‘heightened insecurity’, but to say so would be to reduce the impression that ‘they’ are in control, especially when – as the shooting of innocent Brazilian electrician Jean-Charles de Menezes at Stockwell Tube station showed – they often are not. At the very least, ‘they’ are not as in control as they would like to be. But living as we do in a nation-state with more

security cameras per head of population than any other on earth (London alone has more than many whole countries) – compare any German, or even Russian, airport; their experience of Big Brother is too recent – the ‘security situation’ is a convenient excuse for almost every organ of government, from Whitehall to your local council refuse collection department, to ‘collect evidence’ about ‘miscreant behaviour’. To those who say ‘if you have done nothing, you have nothing to fear’, I would ask only who defines ‘nothing’, and how do you know when – or why – that definition may change?

I am not saying there are no terrorists or no threat. The attacks on New York and the London Underground proved that. What lacks proof is that the risks always inherent in a free society justify

curtailing

that freedom: measures such as locking up citizens for three months without trial or even charge, investigating the contents of rubbish bins or keeping a database of every phone call made, email sent or website looked at, all of which have in recent years been proposed by the government of a country that likes to boast of its people’s freedom and democracy. Recent press exposés of the

corruption

endemic in the British parliament have only proved how important it is for the press to be free, for journalists to be able to report what they see, for the public to have the power to censure governments, rather than governments have the power to censor what the public may see, or do.

I would not have thought, in East Germany in 1989 as we rejoiced at the crumbling of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of corrupt

governments

who thought their power over their populations was total, backed up by policemen – secret or otherwise – who considered themselves unanswerable to the public, that twenty years later, Britain would be a country where politicians tried to use the law to prevent revelation of how they twisted the rules to their own profit, or where policemen would wear masks and illegally cover up their

identifying

numbers to lash out at legitimate demonstrators. No, we are not a worse country today than East Germany was before the Wall came down. But we are not always so very much better as we like to imagine.

The lesson of ‘1989 and all that’ is that history is not something that happens around us. It is something we are part of. For richer, for poorer, for better or worse.

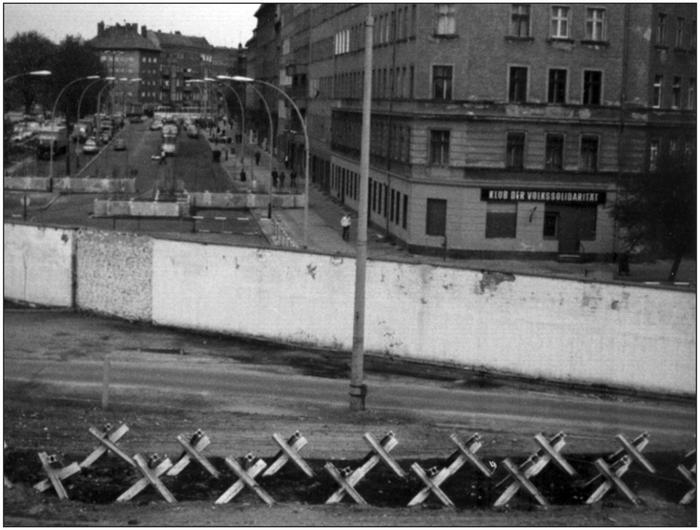

French sector (abandoned piece of wall), 1981

View from the West near our flat, 1981

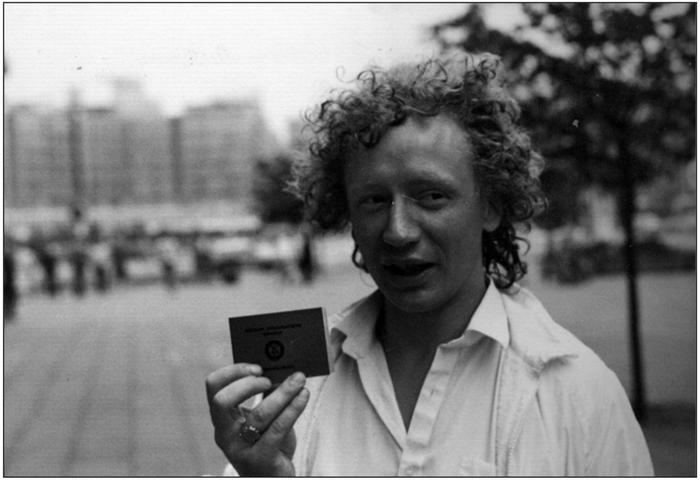

Der Führer(schein) – passing my driving test, 1981

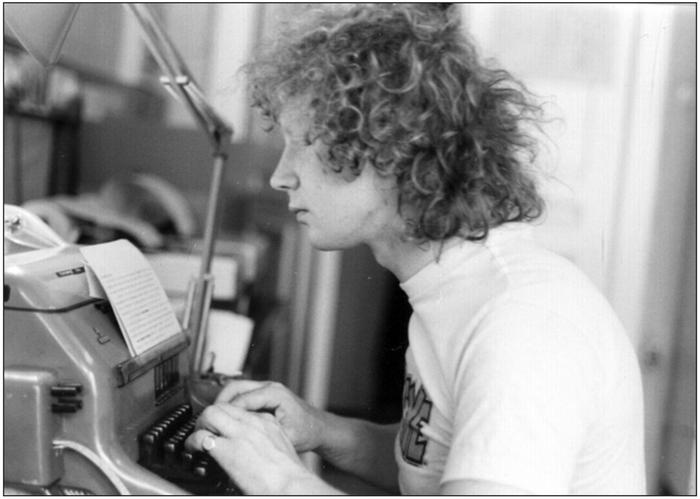

Portrait of the artist as a young hack

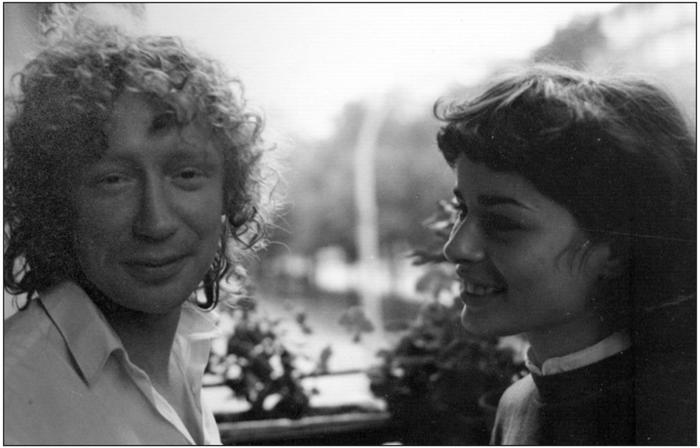

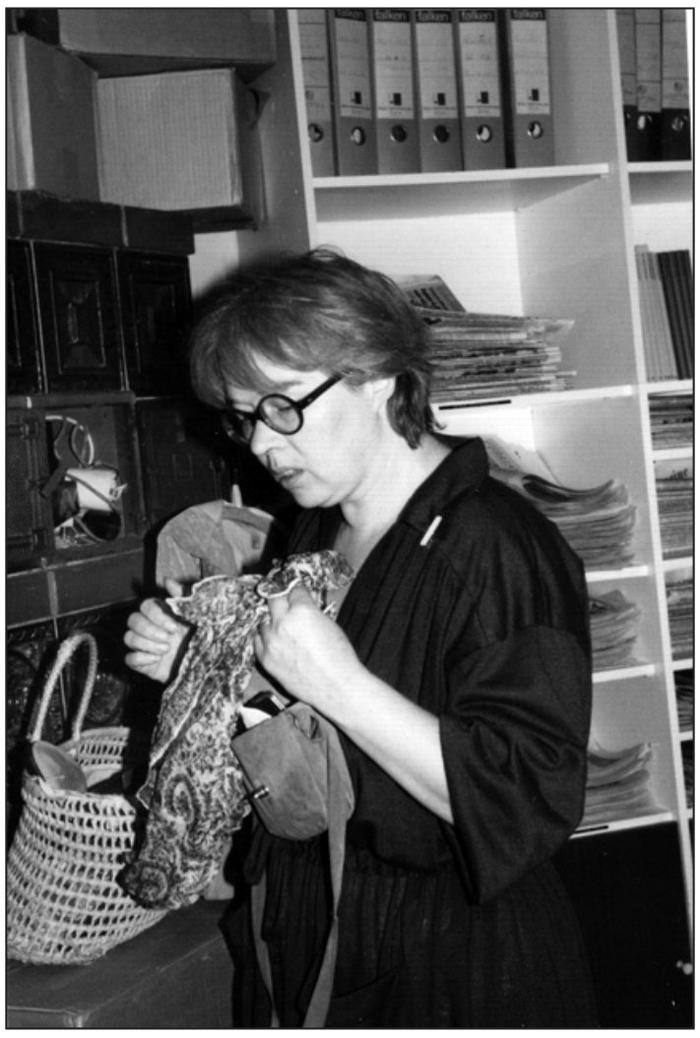

Helga the honeypot

Erdmute the fusspot

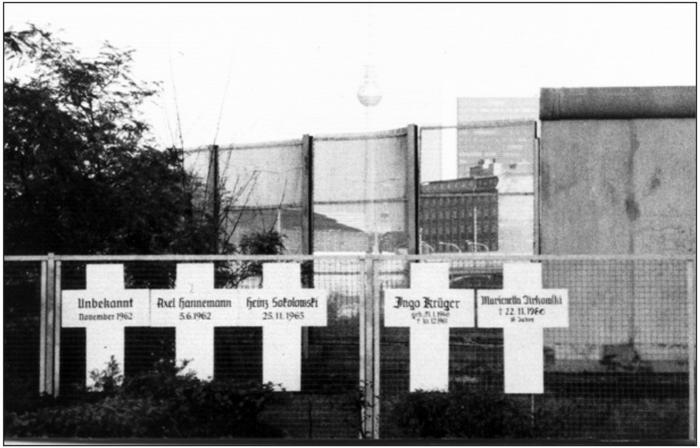

Crosses (in West) commemorating those killed crossing the Wall at this spot

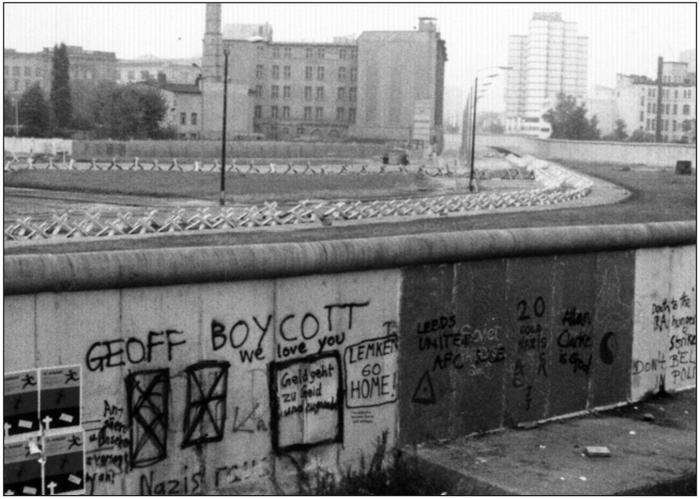

The Wall with contemporary English graffiti – not exactly political (Hitler’s bunker underneath the no-man’s-land)

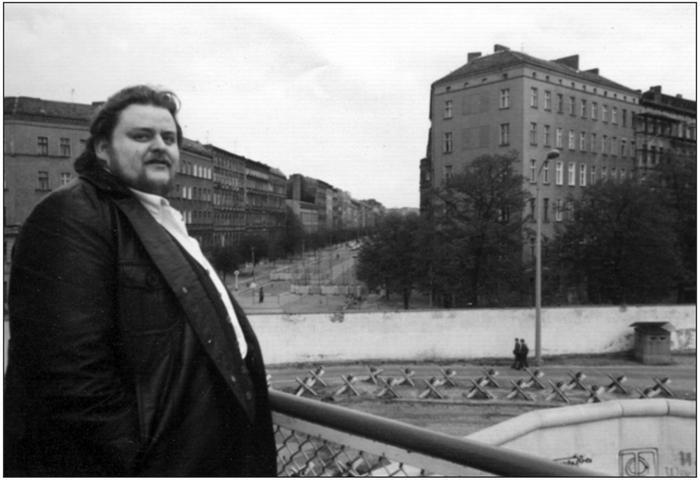

Manne Schulz on his first trip West looks back towards home

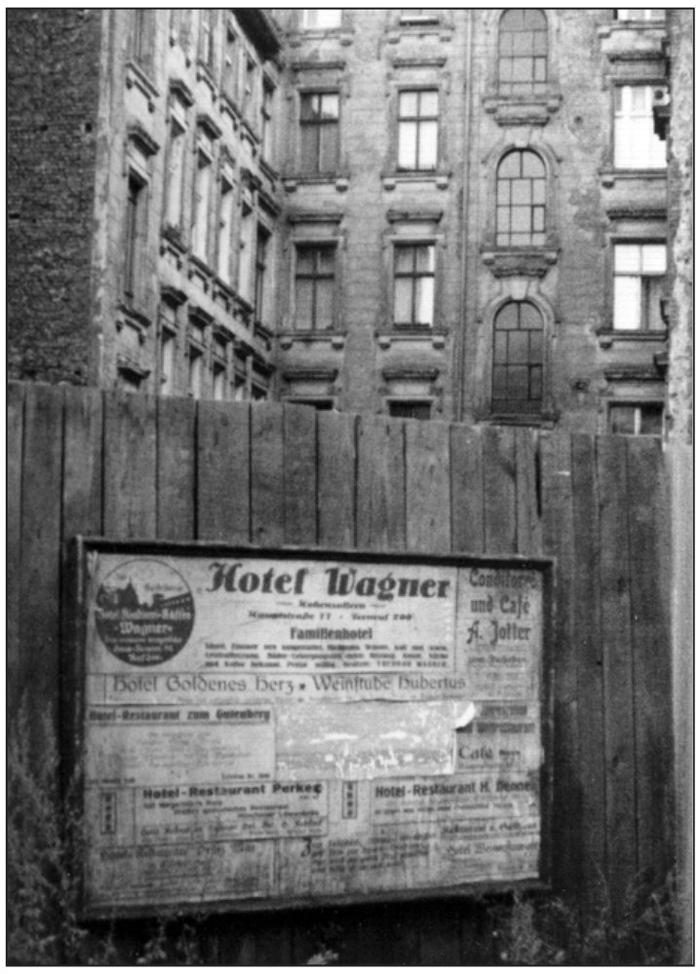

Not quite the best hotel in town, 1981

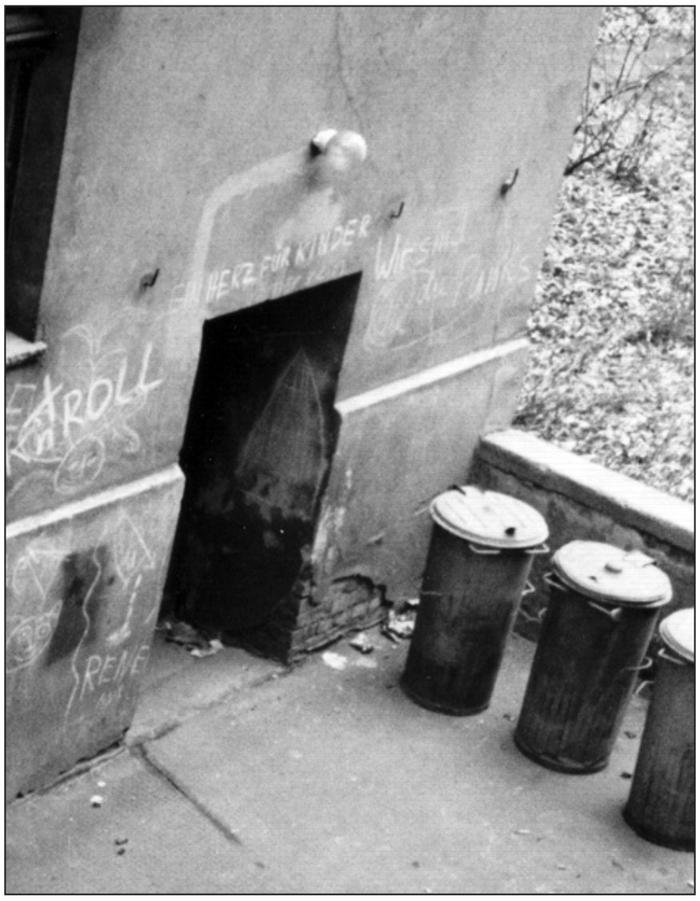

Our back yard (entry to Volker’s flat), 1981

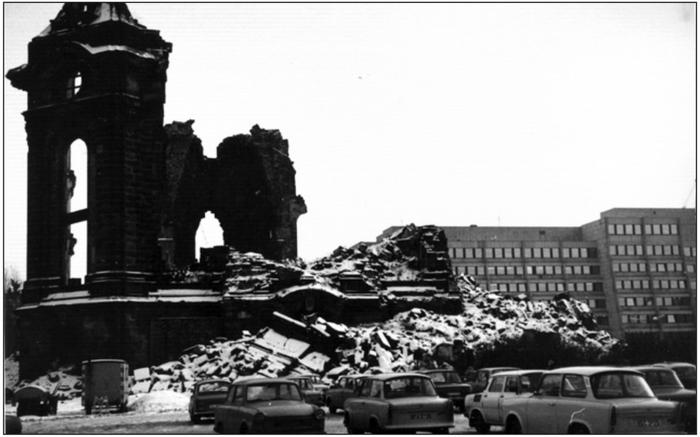

Dresden Frauenkirche ruins – scene of demo, February 1982

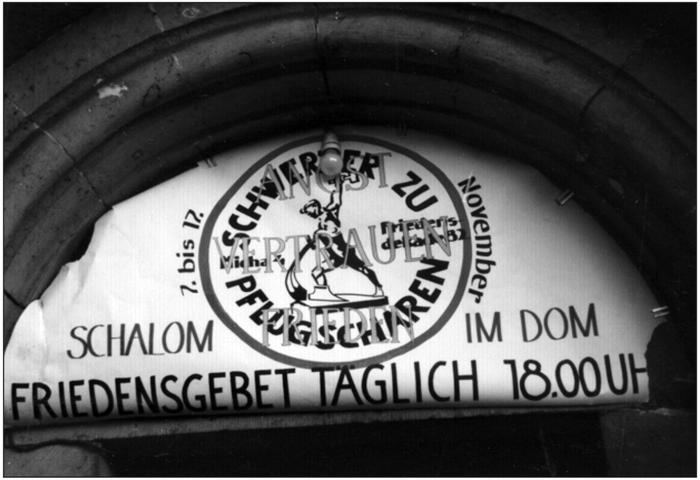

Swords to Ploughshares symbol of protest movement, 1982

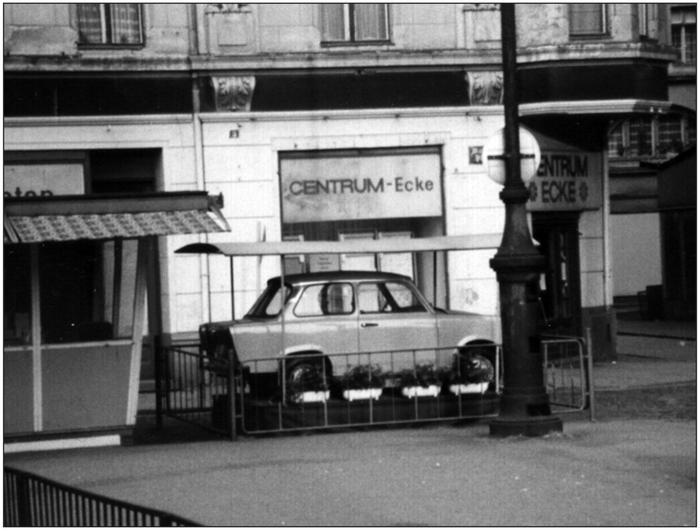

‘You too could win this luxury car!’ Berlin, 1982