1491 (43 page)

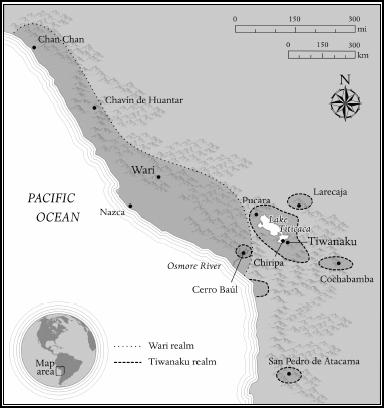

WARI AND TIWANAKU, 700 A.D.

In about 750

A.D.,

about a century after Wari came to Cerro Baúl, Tiwanaku groups infiltrated the region around it. In most places on earth, this encounter would have been fraught with tension. And perhaps if Tiwanaku had been more like Wari there would have been immediate war. But Tiwanaku was so different in so many ways that ordinary expectations rarely apply to it. The celebrated anthropologist Clifford Geertz has half-jokingly suggested that all states can be parceled into four types: pluralist, in which the state is seen by its people as having moral legitimacy; populist, in which government is viewed as an expression of the people’s will; “great beast,” in which the rulers’ power depends on using force to keep the populace cowed; and “great fraud,” in which the elite uses smoke and mirrors to convince the people of its inherent authority. Every state is a mix of all of these elements, but in Tiwanaku, the proportion of “great fraud” may have been especially high. Nonetheless, Tiwanaku endured for many centuries.

Tiwanaku’s capital, Tiwanaku city, was at the southwest end of Lake Titicaca. Situated at 12,600 feet, it was the highest city in the ancient world. Today visitors from lower altitudes are constantly warned that the area is very cold. “Bring warm clothing,” Williams advised me in Cerro Baúl. “You’re going to freeze.” The warnings puzzled me, because Lake Titicaca, which is big enough to stay at a near-constant 51 degrees Fahrenheit, moderates the local climate (this is one reason why agriculture is possible at such height). On winter nights the average temperature is a degree below freezing—cold, but not any colder than New England, and considerably warmer than one would expect at 12,600 feet. Only when I traveled there did I realize that this was the temperature

indoors.

The modern town of Tiwanaku is a poor place and few of its buildings have any heating. One night there I attended a performance at a family circus that was touring the Andes. It was so cold inside the tent that for the first few minutes the audience was shrouded in a cloud of its own breath. My host that night was an American archaeologist. When I woke the next morning in her spare bedroom, my host, in parka, hat, and gloves, was melting water on her stove. The cold does not detract from the area’s beauty: Tiwanaku sits in the middle of a plain ringed by ice-capped mountains. From the ruin’s taller buildings the great lake, almost ten miles to the northwest, is just visible. The wide expanse of water seems to merge into the sky without a welt.

The first important settlement around Titicaca was likely Chiripa, on a little peninsula on the lake’s southwest coast. Its ceremonial center, which may date to 900

B.C.,

was built around a Norte Chico–style sunken plaza. Chiripa was one of half a dozen small, competitive centers that emerged around the lake in that time. Most depended on raised-field agriculture, in which farmers grow crops on flat, artificially constructed surfaces created for the same reason that home gardeners grow vegetables on raised beds. (Similar but even larger expanses of raised fields are found in the Beni, the Mexican basin, and many other places.) By the time of Christ’s birth, two of these early polities had become dominant: Pukara on the northern, Peruvian edge of the lake and Tiwanaku on the opposite, Bolivian side. In the third century

A.D.,

Pukara rather abruptly disintegrated politically. People still lived there, but the towns dispersed into the countryside; pottery making, stela carving, and monument building ceased. No one is certain why.

Although Tiwanaku has been occupied since at least 800

B.C.,

it did not become an important center until about 300

B.C.

and did not expand out from southern Titicaca until about two hundred years after Pukara’s decline. But when it did reach out to its south and west, Tiwanaku transformed itself to become what Alan Kolata, an archaeologist at the University of Chicago, has called a “predatory state.” It was not the centrally administered military power that term conjures. Instead, it was an archipelago of cities that acknowledged Tiwanaku’s religious preeminence. “State religion and imperial ideology,” Kolata argued, “performed much the same work as military conquest, but at significantly lower cost.” Awed by its magnificence, fearful of the supernatural powers controlled by its priesthood, local rulers subordinated themselves.

Central to this strategy of intimidation was Tiwanaku city. A past wonder of the world, it is badly damaged today. In the last two centuries, people have literally carted away many of its buildings, using the stones for churches, homes, bridges, public buildings, and even landfill. At one point the Bolivian government drove a railroad through the site (recently it laid a road through another part). Hands more enthusiastic than knowledgeable reconstructed many of the remaining buildings. Still, enough remains to get a sense of the ancient city.

Dominating its skyline was a seven-tiered pyramid, Akapana, laid out in a pattern perhaps inspired by the Andean cross. Ubiquitous in highlands art, the Andean cross is a stepped shape that some claim is inspired by the Southern Cross constellation and others believe represents the four quarters of the world. Whatever the case, Akapana’s builders planned with a sense of drama. They constructed its base walls with sandstone blocks, the array interrupted every ten feet by rectangular stone pillars that are easily ten feet tall. So massive are the pillars that the first European to see Tiwanaku, Pedro Cieza de León, later confessed himself unable to “understand or fathom what kind of instruments or tools were used to work them.” Rising from the center of a large moat, Akapana mimicked the surrounding mountains. A precisely engineered drainage system added to the similarity by channeling water from a cistern-like well at the summit down and along the sides, a stylized version of rainwater plashing down the Andes.

The Andean cross

Atop an adjacent, somewhat smaller structure, a large, walled enclosure called Kalasasaya, is the so-called Gateway of the Sun, cut from a single block of stone (now broken in two and reassembled). Covered with a fastidiously elaborate frieze, the twelve-foot gateway focuses the visitor’s eye on the image of a single deity whose figure projects from the lintel: the Staff God.

Today the Gateway of the Sun is the postcard emblem of Tiwanaku. During the winter solstice (June, in South America) hundreds of camera-toting European and American tourists wait on Kalasasaya through the entire freezing night for the sunrise, which is supposed to shine through the Gateway on that date alone. Guides in traditional costume explain that the reliefs on the lintel form an intricate astronomical calendar that may have been brought to earth by alien beings. To keep themselves warm during the inevitable longueurs, visitors sing songs of peace and harmony in several languages. Invariably the spectators are stunned when the first light of sunrise appears well to the side of the Gateway. Only afterward do they discover that the portal is not in its original location, and may have had nothing to do with astronomy or calendars.

If those tourists had come to Tiwanaku at its height, walking through the miles of raised fields surrounding it to the city’s carefully fitted stone walls, they would have been delighted by its splendor. But it might also have seemed curiously incomplete, with half the city falling down and in need of repairs and the other half under construction. Modern drawings of ancient cities tend to show them at an imagined apogee, the great monuments all splendidly arrayed together, perfect as architectural models. But this is not what Tiwanaku looked like, nor even what it was

meant

to look like, according to Isbell and Vranich. From the very beginning, the two men wrote in 2004, the city was partly in ruins—intentionally so, because the fallen walls bequeathed on Tiwanaku the authority of the past. Meanwhile, other parts of the city were constantly enveloped in construction projects, which testified to the continued wealth and vitality of the state. Sometimes these projects acquired construction materials by cannibalizing old monuments, thereby hastening the process of creating ruins. In the Andean tradition, labor was probably contributed by visiting work parties. Periodically ritual feasts that included much smashing of pottery interrupted the hubbub of construction. But it always continued. “They build their monuments as if their intent was never to finish them,” the Spanish academic Polo de Ondegardo marveled in 1571. Exactly right, Isbell and Vranich said. Completion was not the object. The goal was a constant buzz of purposeful activity.

As our hypothetical modern visitors wandered through the hurly-burly of construction and deconstruction, they might have felt that despite the commotion something was missing. Unlike Western cities, Tiwanaku had no

markets—

no bazaars full of shouting, bargaining, conniving entrepreneurs; no street displays of produce, pottery, and plonk; no jugglers and mimes trying to attract crowds; no pickpockets. In Africa, Asia, and Europe, Kolata wrote, “a city was a place of meeting and of melding for many different kinds of people…. Through trade and exchange, through buying and selling of every conceivable kind, the city was made and remade.” Tiwanaku was utterly different. Andean societies were based on the widespread exchange of goods and services, but kin and government, not market forces, directed the flow. The citizenry grew its own food and made its own clothes, or obtained them through their lineages, or picked them up in government warehouses. And the city, as Kolata put it, was a place for “symbolically concentrating the political and religious authority of the elite.” Other Andean cities, Wari among them, shared this quality. But Tiwanaku carried it to an extreme.

On Lake Titicaca, the reed boats known as

totora

are still in use, as they have been for two thousand years. This replica of a large

totora

was built in 2001 to prove the vessels could have hauled the big stones used in Tiwanaku’s walls.