(1/20) Village School (25 page)

Read (1/20) Village School Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #Country life, #Country Life - England, #Fairacre (England: Imaginary Place), #Fairacre (England : Imaginary Place)

This remark must have been instantly regretted, so scandalized was the vicar's expression on hearing it, for as well as its derogatory tone about the importance of the Sabbath, he would be celebrating Holy Communion at 7 a.m., 8 a.m., Matins at 11 a.m., Children's Service at 3 p.m., and Evensong at 6.30 p.m.

'Four-thirty at Bunce's then,' he repeated, in a somewhat shaken voice, 'and five-thirty here.'

He stood aside, and with whoops of joy and rattlings of buckets, the youth of Fairacre swept on to the beach with a reckless disregard for kerb drill that made their teacher's blood, if not their parents', run cold.

Miss Clare had decided to take a turn about the shops before going down to the sea and asked me if I would like to accompany her.

'But not, of course, if you would prefer to be elsewhere. It's only that I am looking out for a blue cardigan, something between a royal and a navy, to wear with my grey worsted skirt in the winter.'

I said that there was nothing I should like better than a turn about the shops.

'It would be so useful too, for school,' went on Miss Clare happily, her eyes sparkling at this prospect, 'just in case, you know, I am needed, from the time Miss Gray leaves, until Christmas. The vicar has been so very kind about it all, and I feel so much better for my rest, that I hope I can come back, even if it is only for a few weeks.'

It was nice to see Miss Clare so forward-looking again, and I hoped, for her sake, that the vacancy at Fairacre School would not be filled before the end of next term.

We had a successful shopping expedition. '

Most

suitable, madam,' the girl had gushed, 'and if madam ever indulged in a

blue rinse,

the effect would be quite, quite electrifying.' Digesting this piece of intelligence we made our way to the beach, where, scattered among other families, the Fairacre children could be seen digging, splashing and eating with the greatest enjoyment.

The tide was crawling slowly in over the warm sand, and Ernest was busy digging a channel to meet it. His spade was of sharp metal and cleaved the firm sand with a satisfying crunch. I thought regretfully of my own childhood's spade, a solid wooden affair much despised by me, but nothing would persuade my parents that I would not chop off my own toes and be a cripple for life if I were given a metal one, and so I had had to battle on with my inadequate tool, while more fortunate children sliced away beside me with half the effort, and, as far as my jaundiced eye could see, their full complement of toes.

Ernest paused for a minute in his work.

'Wish we could stay longer here,' he said, 'a day's not long, is it?'

We settled ourselves near him and agreed that it wasn't very long.

'You'd better make up your mind to be a sailor,' I said, nodding to a boat drawn up at the edge of the beach. People were climbing in ready for a trip round the harbour.

'Oh, I wouldn't like that,' responded Ernest emphatically, 'I don't reckon the sea's safe, for one thing. I mean, you might easy get drownded, mightn't you?'

'A lot of people don't,' I assured him, but his brow remained perplexed, working out the countryman's suspicions of a new environment.

'And there don't seem enough grass and trees, somehow. Nor animals. Why, I didn't see any cows or sheep the last bit of the journey. No, I'd sooner live at Fairacre, I reckons, but I'd like to have a good long holiday here.'

Having come to terms with himself he began digging again with renewed effort, and I looked about to see how the other children fared.

The sky was blue but with a fair amount of cloud, which kept the temperature down. Despite this, most of the children seemed content to be in bathing costumes, but it was interesting to see with what respect and awe they treated the sea. Not one of them, it appeared, could swim-not surprising perhaps, when one considered that Fairacre was a downland village and the nearest swimming water was at Caxley, six miles distant.

I wished, not for the first time, that I could see my way clear to taking my older children into the Caxley Swimming Baths once a week, but the poor bus service, combined with the difficulties of rearranging the time-table to fit in this activity, made it impossible at the moment. Paddlers there were, in plenty, but not one of the Fairacre children went more than a yard or two from the beach edge into the surf, and while they stood with the swirling water round their ankles, they kept a weather eye cocked on dry land, ready to make a dash for safety if this strange, unfamiliar element should play any tricks with them.

At digging they came into their own. Armchairs, sand-works, channels, bridges and castles of incredible magnitude were constructed with patience and industry. The Fairacre children could handle tools, and had the plodding unhurried methods of the countryman that produce amazing results. Here was the perfect medium for their inborn skill. The golden sand was turned, raked, piled, patted and ornamented with shells and seaweed, until I seriously thought of importing a few loads into the playground at home to see what wonders they could perform there.

One or two went with their parents for a trip in the boat, but they sat, I noticed, very close to the maternal skirts, and looked at the green water rushing past them with respectful eyes.

The day passed cheerfully and without incident. Tea at Bunce's was the usual happy family affair, held in an upstairs room with magnificent views of the harbour.

'Our Mr Edward Bunce,' as the waiter told us, was in personal attendance on our needs, an elegant figure in chalk-striped flannel and bow tie. Soft of voice and smooth of manner, he swooped around us with the teapot, the living emblem of the personal service which has made Bunce's the great tea-shop that it is.

At five-thirty, we were back in our coaches, with seaweed, shells and two or three unhappy crabs awash in buckets in an inch or two of seawater. The vicar, quite pink with the sea-air, was holding his gold half-hunter and counting heads earnestly.

Mr Annett and Miss Gray mounted the steps in a dazed way and resumed their seat amidst sympathetic smiles, and only one seat then remained empty.

'Mrs Pratt, vicar,' called someone, 'Mrs Pratt and her two little'uns!'

'I think I see one of them, coming across from the chemist's shop,' answered the vicar. A fat little girl in a pink frock stumped across to the coach, panted heavily up the steps and to her place, and sat, swinging her legs cheerfully. We continued to wait. The driver nipped back his little glass window and said:

'That the lot?'

'No, no,' answered Mr Partridge, rather flustered, 'one more and a little boy to come. Peggy, my dear,' he said to the elder Pratt child, 'is your mummy still in the chemist's?'

'Yes,' said the child, smiling smugly. 'Robin's got something in his eye.' She sounded both proud and pleased.

The vicar looked perturbed, and sought his wife's support anxiously. She rose, bustling, from her seat, leaving her gloves and bag neatly behind her.

'I'll just run across to her,' said the good lady and trotted across to the open door of the chemist's shop.

Dimly, in the murk of the interior, we could see figures grouped around a chair, on which, presumably, sat the patient. There were head-shakings and gesticulations, and at length Mrs Partridge came hurrying back with the news.

'The chemist seems to think that the child should see a doctor. He suggests that we take him to the out-patients' department at the hospital. It's quite near here evidently.'

There was what reporters call 'a sensation' at this dramatic announcement. Some were all for getting out of the coach, rushing across to fetch Robin and Mrs Pratt away from all these foreigners, and taking them straight home to their dear familiar Doctor Martin; others suggested that the chemist was a scaremonger, and that 'the bit of ol' whatever-it-is will soon slip out. You knows what eyes is—hell one minute, and all Sir Garnett the next!' But all factions were united in the greatest sympathy for the unfortunate family.

'The child is in great pain,' went on Mrs Partridge, looking quite distracted. 'Cigarette ash evidently, and it seems to have burnt the eye. I really feel that he should go to the hospital.'

'In that case, my dear,' said the vicar, making himself heard with difficulty above the outburst of lamentation that greeted this further disclosure, 'you and I had better stay with Mrs Pratt and see this thing through, while the rest of the party go back to Fairacre.'

'But tomorrow is Sunday!' pointed out his wife.

'Upon my word,' said the vicar, turning quite pink with embarrassment, 'it had slipped my mind.'

'Shall I stop?' I volunteered. At the same time, a voice said:

'What about little Peggy here? Had she better come with us or stay with her mum?'

Bedlam broke out again as everyone offered advice, condolence or reminiscences of past experiences of a similar nature. The driver, who had had his head stuck through his little window, and had been following affairs with grave attention, now said heavily, 'I 'ates to 'urry you, sir, but I'm due back at nine to collect a party of folks after a dance in Caxley; and we're running it a bit fine, if you'll pardon me mentioning it.'

The vicar said that, of course, of course, he quite understood, and then outlined his plan.

'If you will stop with Mrs Pratt and Robin,' he said to his wife, 'I'm sure our good friend Mr Bunce will be able to find you a night's lodging—I will hurry there myself, if the driver thinks we can spare ten minutes.' He looked inquiringly at the driver and received a reassuring nod. He produced his wallet, and there was a flutter of notes between him and Mrs Partridge, 'And then hire a taxi, my dear, to bring you all back tomorrow.' He looked suddenly stricken. 'I shall have to remember to set the alarm clock for early service, of course. I must tie a knot in my handkerchief to remind me.'

This masterly arrangement was applauded by all and we were sitting back congratulating ourselves on our vicar's acumen when a little voice said, 'And what about me?' We all turned to look at Peggy who sat, wide-eyed and rather cross, waiting to hear her fate. There was an awkward pause.

'There's no one at home,' said Mrs Pringle, 'that I do know. Mr Pratt's off doing his annual training with the Terriers.'

'Would you sleep in my house?' I asked her, 'I've got a nice teddy-bear in the spare room.'

This inducement seemed to be successful, for she agreed at once. Mrs Partridge hurried back to tell Mrs Pratt what had been planned, while the vicar sped at an amazing pace back to Bunce's tea-shop, to see if he knew where beds might be engaged for the night.

The coach buzzed with conversation as we waited for the vicar's return.

'Real wonderful, the vicar's been, I reckons.'

'Got a good headpiece on him … and kind with it, proper good-hearted!'

'I feels sorry for that little Robin. Must be painful, that. Poor little toad!'

Peggy elected to sit by me and Miss Clare obligingly took herself and her parcel containing the new winter cardigan to Peggy's vacated seat. In a few minutes a sad little group emerged from the chemist's shop. Robin had a large pad of cottonwool over one eye, securely clamped down with an eye-shade. Mrs Pratt was drying her tears as bravely as she could, while Mrs Partridge held Robin by one hand, and Mrs Pratt's shopping bag in the other. They approached the coach and made their farewells.

'You be a good girl now, Peg,' adjured her tearful mother, 'and do as Miss Read tells you. And if you'd be so kind as to keep a night-light burning, Miss, I'd be real grateful—she gets a bit fussed-up like if she wakes up in the dark. High strung, you know.'

I assured her that Peggy should have all she wanted, and amid sympathetic cries and encouragement the three made their farewells and departed in the direction of Bunce's.

In record time, the vicar reappeared. Mr Bunce's own sister had obliged with most suitable accommodation and had offered to accompany the Fairacre party to the hospital, in the kindest manner, said the vicar.

The driver set off at once and the great coach made short work of the miles between Barrisford and Fairacre.

Nine o'clock was striking from St Patrick's church as we clambered out and within half an hour, Peggy Pratt was sitting up in the spare bed, drinking hot milk and crunching ginger-nuts. A candle was alight on the chest of drawers, its flame shrinking and stretching in the draught from the open door.

'I likes this nightie,' said the child, looking admiringly at a silk vest of mine that was doing duty as nightgown for my small guest. There had been no tears and no pining for the distant mother and little brother left behind at Barrisford. I hoped that she would fall asleep quickly before she had time to feel homesick.

'I shall leave the door open,' I told her, tucking in the moth-eaten teddy beside her, 'in case you want me. And in the morning we'll have some boiled eggs for breakfast that Miss Clare's chickens laid yesterday.' I took her mug and plate and went to the door.

She wriggled down among the pillows, smiled enchantingly, sighed, and closed her eyes. She was asleep, I think, before I had reached the foot of the stairs.

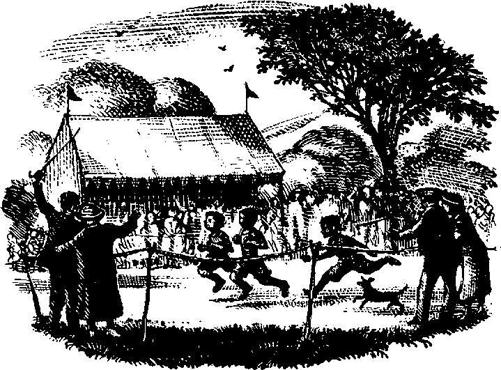

23. Sports Day