(1/20) Village School

Read (1/20) Village School Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #Country life, #Country Life - England, #Fairacre (England: Imaginary Place), #Fairacre (England : Imaginary Place)

| Village School | |

| Fairacre [1] | |

| Miss Read | |

| Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (1976) | |

| Rating: | ★★★★☆ |

| Tags: | Fiction, Country Life, Fairacre (England : Imaginary Place), Country Life - England, Fairacre (England: Imaginary Place) Fictionttt Country Lifettt Fairacre (England : Imaginary Place)ttt Country Life - Englandttt Fairacre (England: Imaginary Place)ttt |

Review

"If you've ever enjoyed a visit to Mitford, you'll relish a visit to Fairacre." -- Jan Karon

Product Description

The first novel in the beloved Fairacre series, VILLAGE SCHOOL introduces the remarkable schoolmistress Miss Read and her lovable group of children, who, with a mixture of skinned knees and smiles, are just as likely to lose themselves as their mittens. This is the English village of Fairacre: a handful of thatch-roofed cottages, a church, the school, the promise of fair weather, friendly faces, and good cheer -- at least most of the time. Here everyone knows everyone else's business, and the villagers like each other anyway (even Miss Pringle, the irascible, gloomy cleaner of Fairacre School). With a wise heart and a discerning eye, Miss Read guides us through one crisp, glistening autumn in her village and introduces us to a cast of unforgettable characters and a world of drama, romance, and humor, all within a stone's throw of the school. By the time winter comes, you'll be nestled snugly into the warmth and wit of Fairacre and won't want to leave.

Village School

Miss Read

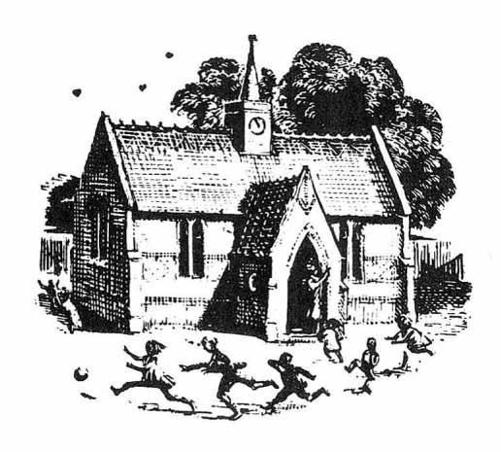

Illustrated by J. S. Goodall

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Boston New York

First Houghton Mifflin paperback edition 2001

Copyright © 1955 by Dora Jessie Saint

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Visit our Web site:

www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com.

Library of Congress catalog card number: 56-7240

ISBN

0-618-12702-

X

Printed in the United States of America

QUM

10 9 8

PART ONE

Christmas Term

1. Early Morning

T

HE

first day of term has a flavour that is all its own; a whiff of lazy days behind and a foretaste of the busy future. The essential thing, for a village schoolmistress on such a day, is to get up early.

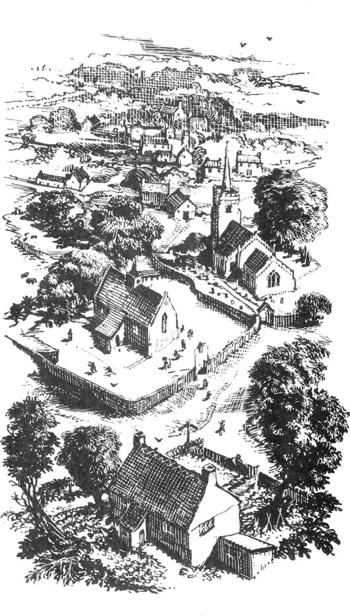

I told myself this on a fine September morning, ten minutes after switching off the alarm clock. The sun streamed into the bedroom, sparking little rainbows from the mirror's edge; and outside the rooks cawed noisily from the tops of the elm trees in the churchyard. From their high look-out the rooks had a view of the whole village of Fairacre clustered below them; the village which had been my home now for five years.

I had enjoyed those five years—the children, the little school, the pleasure of running my own school-house and of taking a part in village life. True, at first, I had had to walk as warily as Agag; many a slip of the tongue caused me, even now, to go hot and cold at the mere memory, but at last, I believed, I was accepted, if not as a proper native, at least as 'Miss Read up the School,' and not as 'that new woman pushing herself forward!'

I wondered if the rooks, whose clamour was increasing with the warmth of the sun, could see as far as Tyler's Row at the end of the village. Here lived Jimmy Waites and Joseph Coggs, two little boys who were to enter school today. Another new child was also coming, and this thought prodded me finally out of bed and down the narrow stairs.

I filled the kettle from the pump at the sink and switched it on. The new school year had begun.

Tyler's Row consists of four thatched cottages and very pretty they look. Visitors always exclaim when they see them, sighing ecstatically and saying how much they would like to live there. As a realist I am always constrained to point out the disadvantages that lurk behind the honeysuckle.

The thatch is in a bad way, and though no rain has yet dripped through into the dark bedrooms below, it most certainly will before long. There is no doubt about a rat or two running along the ridge, as spry as you please, reconnoitring probably for a future home; and the starlings and sparrows find it a perfect resting-place.

'They ought to do something for us,' Mrs Waites told me, but as 'They,' meaning the landlord, is an old soldier living with his sister in the next village on a small pension and the three shillings he gets a week from each cottage (when he is lucky), it is hardly surprising that the roof is as it is.

There is no drainage of any sort and no damp-course. The brick floors sweat and clothes left hanging near a wall produce a splendid crop of prussian blue mildew in no time.

Washing-up water, soap-suds and so on are either emptied into a deep hole by the hedge or flung broadcast over the garden. The plants flourish on this treatment, particularly the rows of Madonna lilies which are the envy of the village. The night-cart, now a tanker-lorry, elects to call in the heat of the day, usually between twelve and one o'clock, once a week. The sewerage is carried through the only living-room and out into the road, for the edification of the schoolchildren who are making their way home to dinner, most probably after a hygiene lesson on the importance of cleanliness.

In the second cottage Jimmy Waites was being washed. He stood on a chair by the shallow stone sink, submitting meekly to his mother's ministrations. She had twisted the corner of the face-flannel into a formidable radish and was turning it remorselessly round and round inside his left ear. He wore new corduroy trousers, dazzling braces and a woollen vest. Hanging on a line which was slung across the front of the mantelpiece, was a bright blue-and-red-checked shirt, American style. His mother intended that her Jimmy should do her credit on his first day at school.

She was a blonde, lively woman married to a farmworker as fair as herself. 'I always had plenty of spirit,' she said once, 'Why, even during the war when I was alone I kept cheerful!' She did, too, from all accounts told by her more puritanical neighbours; and certainly none of us is so silly as to ask questions about Cathy, the only dark child of the six, born during her husband's absence in 1944.

Cathy, while her brother was being scrubbed, was feeding the hens at the end of the garden. She threw out handfuls of mixed wheat and oats which she had helped to glean nearly a year ago. This was a treat for the chickens and they squawked and screeched as they fought for their breakfast.

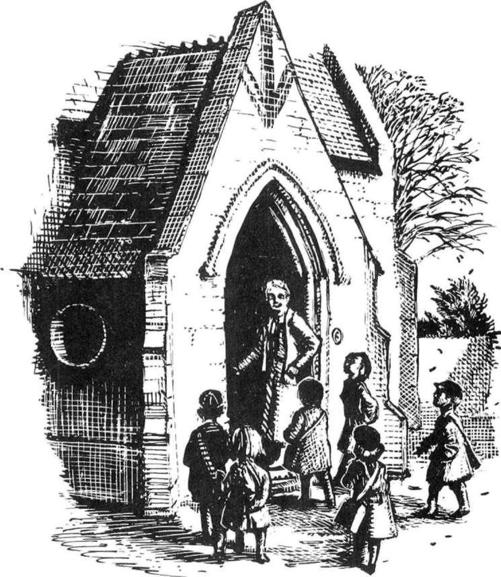

Their noise brought one of the children who lived next door to a gap in the hedge that divided the gardens. Joseph was about five, of gipsy stock, with eyes as dark and pathetic as a monkey's. Cathy had promised to take him with her and Jimmy on this his first school morning. This was a great concession on the part of Mrs Waites as the raggle-taggle family next door was normally ignored.

'Don't you play with them dirty kids,' she warned her own children, 'or you'll get Nurse coming down the school to look at you special!' And this dark threat was enough.

But today Cathy looked at Joseph with a critical eye and spoke first.

'You ready?'

The child nodded in reply.

'You don't look like it,' responded his guardian roundly. 'You wants to wash the jam off of your mouth. Got a hanky?'

'No,' said Joe, bewildered.

'Well, you best get one. Bit of rag'll do, but Miss Read lets off awful if you forgets your hanky. Where's your mum?'

'Feeding baby.'

'Tell her about the rag,' ordered Cathy, 'and buck up. Me and Jim's nearly ready.' And swinging the empty tin dipper she skipped back into her house.

Meanwhile, the third new child was being prepared. Linda was eight years old, fat and phlegmatic, and the pride of her fond mother's heart. She was busy buttoning her new red shoes while her mother packed a piece of chocolate for her elevenses at playtime.

The Moffats had only lived in Fairacre for three weeks, but we had watched their bungalow being built for the last six months.

'Bathroom and everything!' I had been told, 'and one of those hatchers to put the dishes through to save your legs. Real lovely!'

The eagle eye of the village was upon the owners whenever they came over from Caxley, our nearest market-town, to see the progress of their house. Mrs Moffat had been seen measuring the windows for the curtains and holding patterns of material against the distempered walls.

'Thinks herself someone, you know!' I was told later. 'Never so much as spoke to me in the road!'

'Perhaps she was shy.'

'Humph!'

'Or deaf, even.'

'None so deaf as those that won't hear,' was the tart rejoinder. Mrs Moffat, alas! was already suspected of that heinous village crime known as 'putting on side.'

One evening, during the holidays, she had brought the child to see me. I was gardening and they both looked askance at my bare legs and dirty hands. It was obvious that she tended to cosset her rather smug daughter and that appearances meant a lot to her, but I liked her and guessed that the child was intelligent and would work well. That her finery would also excite adverse comment among the other children I also surmised. Mrs Moffat's aloofness was really only part of her town upbringing, and once she realized the necessity for exchanging greetings with every living soul in the village, no matter how pressing or distracting one's own business, she would soon be accepted by the other women.

Linda would come into my class. She would be in the youngest group, among those just sent up from the infants' room where they had spent three years under Miss Clare's benign rule. Joseph and Jimmy would naturally go straight into her charge.

At twenty to nine I hung up the tea towel, closed the back door of the school-house and stepped across the playground to the school.