100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (12 page)

Read 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die Online

Authors: Jon Weisman

27. Arrive Late, Leave Early

So, whenever a book about the Dodgers is published, does a fan of another team joke that the readers start reading in the third chapter and finish in the seventh? Maybe. And maybe it's even funny the first time someone says it. But not the second, or the third, or the three-hundredth.

If you're taking in a national or out-of-town broadcast from Dodger Stadium, it's inevitable that the so-called wit of some announcer will find its target in the ritual late arrival and early departure of Dodgers fans. If it's true fans are like this in Los Angeles, it's also true they're like this at major league parks across the country, with nary a person commenting. And this doesn't even address the ballparks where most of the seats are empty from start to finish.

It may be fair to say, however, that no city is quite like Los Angeles for a

laissez-faire

attitude toward seeing nine innings of baseball. Part of this is inspired by the geographical spread of Los Angeles, its epic traffic, and the notoriously crowded Dodger Stadium parking lots that are barely mitigated by the area's patchy public transportation system. Given those elements, it's no wonder fans are late or fear a homeward struggle.

There are Dodgers fans who will leave at a certain inning by rote, regardless of the hour, how close the game is, or how quickly the game is moving. When Montreal righty Dennis Martinez was pitching the 13th perfect game in major league history at Dodger Stadium in 1991, more than a few folks headed for the exits before the ninth.

But you know what? Not every person in the ballpark that day was a baseball fan. Not everyone who goes to a baseball game lives and dies with the sport. Not everyone has the kind of life that allows one to get to a game on time or stay until the end. So? Isn't it better that people get a taste of the ballpark, however shortened, than no taste at all?

To interject a personal momentâ¦one time my shift at work ended in the neighborhood of midnight. In my car, I listened to a Dodgers game that had entered extra innings. Instead of heading home, I decided to drive to the ballpark and see if the game was still going by the time I got there. Sure enough, I entered Dodger Stadium in the top of the 12

th

inningâand left triumphantly after the Dodgers won it in the bottom of the 12

th

. I saw one inning, and it was one of the most memorable games I have ever attended.

On some level, it's been decided that giving tardy slips or detention to baseball fans is a way of measuring their dedication, their innate “fanness.” That's not going to change, but the methodology isn't fail-safe. The Dodgers have sold more tickets than any franchise in history. Even after accounting for those who don't see a full game, it's doubtful there are many other fan bases that have seen more innings of baseball than the one in Los Angeles. And the passion of Dodgers fans, whether they're at the game or listening to Vinny (the No. 1 reason for not rushing to one's seat), has always been underrated.

Baseball is supposed to be fun. Baseball is not football or basketball with rigid time constraints. Baseball is a carefree day at the park, a night to unwind. No doubt, there are some of you who want to see nine innings of ball but just can't. But if you're pleased with less, then be pleased. Arrive late and leave early, and do it to your hearts' content. This is not a test.

What Goes Around, Comes AroundâAnd Smacks You

If you don't like seeing dramatic comebacks at the Dodgers expense, then August 21, 1990, was the night to leave Dodger Stadium early. Los Angeles built an 11â1 lead over Philadelphia, thanks largely to an eight-run fifth inning, and still led 11â3 heading into the ninth.

But the Phillies started stringing some singles and walks (with two errors by Dodger shortstop Jose Offerman tying it all together) that cut into the Dodger lead. Dale Murphy doubled off Tim Crews with the bases loaded to pull the Phillies within reach at 11â8, and John Kruk immediately followed with a pinch-hit three-run homer to tie the game. Two batters later, Jay Howell then gave up a double to Carmelo Martinez that drove in Philadelphia's ninth run in the ninth, the deathblow in a 12â11 loss for the Dodgers.

Postgame traffic was light, but heavy-hearted.

28. Hail the Duke of Flatbush

“With two runners on base and the Dodgers leading 5â4 in the 12

th

inning, Willie Jones drove a 405-footer up against the left-center-field wall. Duke isn't a look-and-run outfielder like Mays. He prefers to keep the ball in view all the time if possible, and he was judging this one every step of his long run to the wall. There it seemed he was climbing the concrete âon his knees,' as awed Dodger coach Ted Lyons put it. Up and up he went like a human fly to spear the ball, give a confirming wave of his glove and fall backward to the turf. The wooden bracing on the wall showed spike marks almost as high as his head. It was such a catch that, although it saved the game for Brooklyn, admiring Philly fans swarmed the field by the dozens. Duke lost his cap and part of his shirt and almost lost his belt.”

â Al Stump,

Sport

Â

Edwin Donald Snider gets third billing in the Terry Cashman song, “Willie, Mickey, and the Duke”âa placement that seems to celebrate as well as diminish his legacy. Snider was one of the greatest center fielders of all time, up there with Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle, but he was forever proving himself to the Dodgers and to baseball history.

“Duke was so talented, and he had a grace about him,” said his Dodgers roommate for 10 years, Carl Erskine. “They talk about [Joe] DiMaggio and how he carried himself on the field.⦠His outfield play and his running the bases and his trot for the home run, he just looked class, man.

“The thing that bothered Duke was, no matter how well he did, the coaches [and] managers always said, âHe can do better than that.' They always kind of made Duke feel no matter how hard he tried, he couldn't satisfy everybody. It was bothersome for him.”

Â

Â

Â

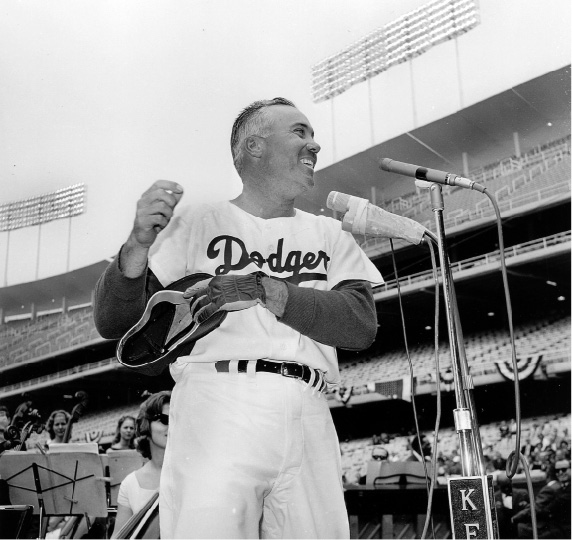

Longtime Dodgers center fielder Duke Snider greets invited guests to the “sneak peek” of the new Dodger Stadium on April 9, 1962. “The Duke of Flatbush” played his final season at Dodger Stadium, was the franchise leader in home runs at 389, and played on two Dodgers world championship teams in 1955 and 1959.

Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Times Collection, UCLA Library Special Collections.

Â

Snider, a Compton High School graduate from Los Angeles, even had a love-hate relationship with Ebbets Field fans, as Maury Allen writes in

Brooklyn Remembered.

“Snider always wore his emotions on his sleeve,” Allen said. “A home run in a key spot would produce that Hollywood handsome grin. A strikeout with the bases loaded and the Brooklyn fans booing his very name announcement the next day would result in a week of sulkiness.”

Ultimately, like the way he climbed that Ebbets Field wall to save the game against the Phillies, Snider reached magnificent heights. He had eight full seasons and two partial seasons with TAvs of .300 or better, more than any other Dodger ever. He had at least 40 homers in the Dodgers' five final seasons in Brooklyn, and a career .295 batting average, .380 on-base percentage, and .540 slugging percentage. He hit an all-time Dodgers record 389 homers.

In a 1955 article,

Sports Illustrated

chose Snider over Willie Mays: “In every sense, the contemporary hero of Flatbush, prematurely gray at the temples in his 29

th

year, is a picture player with a classic stance that seldom develops a hitch. Next to [Ted] Williams, Snider probably has the best hitting form in the game. And, like Williams, he has amazing eyesâlarge, clear, calm, and probing. With each oncoming pitch, Snider tenses and then throws his full 195 pounds into it, if he swings, with a smooth, lashing motion.”

The Duke was much, much more than a name in a song.

15-Love

May 21, 1952: Just another lovely night at Ebbets Field, the Dodgers facing the Cincinnati Reds. Billy Cox leads off the bottom of the first by grounding out, but Pee Wee Reese walks and Duke Snider homers over the right-field scoreboard. Would that be enough?

Maybe this would help: Jackie Robinson speeds to a double on a Texas leaguer, then after an Andy Pafko walk, scores on a George Shuba single. Pafko was thrown out at third on an attempted double steal, but perhaps a 3â0 lead would suffice.

Just in case it wouldn't, the Dodgers eke acrossâ¦12 more runs. The next 14 Dodger batters all reach base on seven singles, five walks, and two batters hit by pitches. Reese alone notches a single and two walks in the inning. Finally, with the bases loaded, Snider takes a curveball from Frank Smith, the fourth Reds pitcher, for a called strike three, and the Dodgers settle for a 15â0 lead, the biggest first-inning onslaught in big league history.

And yes, pitcher Chris Van Cuyk, who went 4-for-5 at the plate, is able to make the lead stand up for a 19â1 Dodger victory.

29. 1965

A catharsis of a different kind. Two years after their fulfilling, resounding sweep of the Yankees, the once-snakebitten Dodgers won another World Seriesâthe team's third in Los Angeles and fourth since 1955. But 1965's triumph came at the end of an exhausting season of scratching and clawing and self-medicating that elicited as much relief as elation.

It was a year most remembered for two grit-your-teeth moments: Giants pitcher Juan Marichal using Dodgers catcher Johnny Roseboro's head for batting practice, and Sandy Koufax's perfect game that the Dodgers offense backed with a single hit. It was a year that the only Dodger to bat .300 or slug .400 was pitcher Don Drysdale, who was 39-for-130 with seven homers.

Down 4

1/2

games to the Giants on September 15, the Dodgers found the way to win 13 straight and 15 of their final 16, allowing only 17 runs over that stretch. On October 1, Koufax struck out 13 in clinching the title for the Dodgers with a 3â1 victory over the Milwaukee Braves. How did the Dodger offense break a 1â1 tie in the fifth? Almost inexplicable bases-loaded walks to Roseboro and Koufax.

There was every indication that the Dodgers were spent by the time the World Series began in Minnesota on October 6: Yom Kippur that year. Famously, Drysdale got the Game 1 start instead of Koufax, and when Walter Alston met Roseboro and Drysdale at the pitcher's mound to pull him during a six-run third inning, the pitcher supposedly quipped, “I bet you wish I was Jewish, too.” (Rob Neyer, in his

Big Book of Baseball Legends,

investigated the story and found that “all three of these men later composed their memoirs [Alston twice], and yet none of them happened to mention this seemingly memorable joke that Drysdale made.⦠A check of various newspaper archives doesn't find it attributed to Drysdale until the 1980s, usually in reference to Sandy Koufax and the status of the Jewish ballplayer.”) No matterâthe tale spoke volumes, with the added irony that on Game 2 the following afternoon, Alston probably wished Yom Kippur had returned in time to prevent Koufax from allowing two runs in the sixth inning of a scoreless contest. The Dodgers lost the game 5â1 and headed back to Los Angeles in a 2â0 Series hole.

Â

Â

Â

Sandy Koufax and Lou Johnson were Game 7 heroes of the 1965 World Series. The Dodgers defeated the Minnesota Twins 2â0. Koufax pitched a complete-game shutout and Johnson drove in the initial run with a home run.

Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Dodgers, Inc. All rights reserved.

Â

In Game 3, the Dodgers' one major preseason acquisition paid its greatest dividend. Claude Osteen, acquired in a deal that marked the departure of slugger Frank Howard, threw a 4â0 shutout backed by RBI hits from Roseboro, Lou Johnson, and Maury Wills that put the Dodgers back in Series contention. A three-run sixth gave Drysdale breathing room in a 7â2 Game 4 victory, and then Wills' four hits helped Koufax cruise to a 7â0 Game 5 shutout, in which he took a perfect game into the fifth inning and a two-hitter into the ninth.

But nothing was going to be entirely easy for the Dodgers, not this year. Back in Mnnesota, Mudcat Grant hit a three-run homer while pitching a complete-game 5â1 victory on two days' rest, setting up the Dodgers' first Game 7 since '55.

Koufax and Jim Kaat, also pitching on two days' rest, started out scoreless through three innings. Then, leading off the top of the fourth, “Sweet” Lou hooked one off the left-field foul pole to put the Dodgers on the scoreboard and give Koufax the only run anyone ever hoped he would need. Wes Parker's high chopper over first base to drive in Ron Fairly that same inning seemed almost luxurious in context.

Koufax, who later said he relied on fastballs because his curveball had abandoned him, would get even more help. In the bottom of the fifth, with runners on first and second and one out, Jim Gilliamâwho began the season as a Dodgers coachâmade a sprawling, backhanded stop of Zoilo Versailles' grounder for a force play that helped preserve Koufax's shutout.

In the ninth, a one-out single by Harmon Killebrew gave the Twins two final chances to tie the score. But Koufax fanned Earl Battey and Bob Allison to end it. A very much non-leaping Koufax, who had struck out 29 in 24 innings over nine days while allowing one earned run, joined the Dodgers in thankful celebration. In the clubhouse after the game, Vin Scully reminded Koufax that after that Game 5, Koufax said he felt 100 years old. “So today,” Scully asked him, “how do you feel?”

“A hundred and one,” Koufax replied. “I feel great, Vinny, and I know that I don't have to go out there any more for about four months.”

Â

Â

Zero for '66

Dodgers futility never got a more public airing than the 1966 World Series against the Baltimore Orioles. In Game 1, Jim Lefebvre homered in the bottom of the second inning, and Jim Gilliam walked with the bases loaded in the third. That was itâthe team was done. For the remaining 33 innings, the Dodgers did not score. Only two Dodger base runners reached third base. The nadir was Game 2, when the Dodgers made six errors, three in the space of two batters by center fielder Willie Davis, though back-to-back 1â0 losses in Games 3 and 4 offered their own special brand of excruciation. The Dodger doldrums began in earnest in 1967, after Sandy Koufax retired, but the entry point was here.