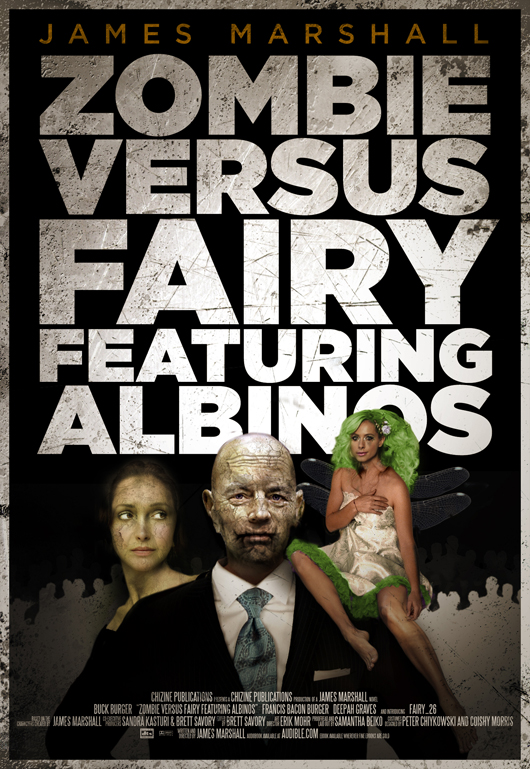

Zombie Versus Fairy Featuring Albinos

Read Zombie Versus Fairy Featuring Albinos Online

Authors: James Marshall

NINJA VERSUS PIRATE

FEATURING ZOMBIES

“Chaotic, crazy, and undeniably captivating,

NVPFZ

is the quirkiest take yet on the zombie genre. First in a series that is sure to be a smash with the gaming generation.”

—Library Journal

“. . . if you’re anything like me, you will laugh hysterically and feel vaguely guilty over it and wonder if maybe there’s something wrong with you.”

—Carrie Harris,

author of

Bad Taste in Boys

“Readers who like their literary escapism on the psychotropic side should definitely seek out and read this stroboscopic debut. Bomb disposal suit not included—but highly recommended.”

—Barnes & Noble

“. . . a good old-fashioned spin-your-head-around-twice mindfu@#.”

—Corey Redekop,

author of

Husk

ChiZine Publications

Zombie Versus Fairy Featuring Albinos

© 2013 by James Marshall

Cover artwork © 2013 by Erik Mohr

Cover design © 2013 by Samantha Beiko

Interior design © 2013 by Danny Evarts

All rights reserved.

Published by ChiZine Publications

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either a product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

EPub Edition APRIL 2013 ISBN: 978-1-92748-142-7

All rights reserved under all applicable International Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews.

CHIZINE PUBLICATIONS

Toronto, Canada

www.chizinepub.com

[email protected]

Edited and copyedited by Samantha Beiko

Proofread by Kelsi Morris and Zara Ramaniah

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $20.1 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada.

Published with the generous assistance of the Ontario Arts Council.

CHAPTER ONE

A Depressed Zombie In The

Anti-Depression–Era Depression

CHAPTER TWO

A If My Wife Wasn’t Already Dead,

I’d Probably Kill Her

CHAPTER THREE

The Illusion Of Differencer

CHAPTER FOUR

Farm-Raised Humans Don’t Taste

As Good As Free-Range

CHAPTER SIX

All Human Children Are Born

Of Zombies

CHAPTER SEVEN

Word Came From On High

CHAPTER EIGHT

Who’s Using Our Brains?

CHAPTER NINE

You Might Act In A Way Contrary

To Your Best Interest

CHAPTER TEN

Think Of Zombies As A Whole

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Why Does Barry Graves Care?

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Zombie Marriage Counselling

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

The Biohazard I Am

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Aircraft Carrier / Pirate Ship

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Trying Not To Want What I Want

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

A Celebratory Ham

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

Everything Human And Afraid

CHAPTER NINETEEN

We Need To Talk

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

I Know You’re Married And

You’re A Zombie But I Can’t

Help The Way I Feel

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

Buck Burger, Where On God’s

Zombie-Infested Dystopia Have

You Been?

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

Everything Seems To Happen Now

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

The Destruction Starts Again

Tomorrow

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

We Need, or Think We Do

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

He’s Great Until You Find Out He’s

A Zombie And He Ate Your Cat

ONE

A Depressed Zombie In The

Anti-Depression–Era Depression

I yell at my wife, Chi, asking her if she washed my pants, and she hollers back, “No, of course not,” and I yell, “They look clean,” and a few seconds later, she staggers into the bedroom carrying a human foot.

She grinds it—the ragged skin, chewed meat, dried blood part—onto my thigh. “Better?” she asks, staring at the new stain on my trousers.

I look down at it, disgusted. “Yeah.” I hate this. All of this. I despise it. I loathe my life. I detest everyone and everything in it. It’s torture to me: the routine, the monotony, the drudgery.

A couple of nights ago, I heard Chi talking to one of her friends. “I always wanted a man who could cry,” she said. “Just not all the time.”

Now, staring at the blood-stain she just smeared onto my trousers, not hiding the irritation in her voice, she says, “Why couldn’t you do that yourself, Buck?”

I undo the top two buttons of my shirt. “I’m helpless.” I jerk my tie to the side.

“I don’t know what you’d do,” she agrees, “if I wasn’t around.”

The other night, while eavesdropping on Chi, I overheard her say, conspiratorially, “His emotions aren’t the only part of him to go soft, if you know what I’m saying.”

Constance, the cat, slinks into the bedroom. Constance mocks me constantly. She’s so at ease. So self-assured. She’s so comfortable in her own skin. I hate her. The fire of life burns under her ash-grey coat.

Chi throws the human foot against the wall as hard as she can. When it hits the floor, Constance hurries over to it and starts nibbling. As Constance eats, Chi lurches around our bedroom, messing things up. She pulls apart a pillow’s stuffing, scattering it on the unmade bed. She jerks out the only drawer left in the dresser, dropping it on the floor. The drawer is empty, like the gesture. Chi performs these actions without thinking. She does them because she’s supposed to. Like somebody is watching. “What time is your appointment again?”

“Three.” I tuck in my shirt. Then I yank out half of it.

“You tell him you took a shower.”

“I will.”

“And you used soap.”

“I’ll tell him.”

“I can still smell you.” When she turns on me, I can tell by her expressionless face and emotionless eyes she’s revolted.

Constance stops nibbling on the human foot and looks at me, judgmentally. She finds me wanting. Lacking.

“I’ll roll around in some garbage before I get to work.”

“You’d better.”

Our non-living room is covered in blood: the hardwood floor is streaked with it; the walls are splattered with it; there’s a lot on the ceiling. When you walk into the non-living room, you think, “Something terrible happened here.” And it did. And it keeps happening. The smell is atrocious. It’s feces mixed with sick. You can’t breathe. You gag. Flies aren’t individual insects here. They’re cells. They form a loose body. A monster. A cloud that swarms. It’s a panic attack. It eats and waits. For what? More to eat and its babies? Is there any difference?

When she finished decorating it, Chi looked at me, satisfied, and said, “What do you think?”

I didn’t say, “I’m a zombie.” I didn’t say, “I don’t think.” Instead, I said, “It’s good, Chi.”

Before I leave for work, I watch my wife. She stumbles around on broken grey high heels, making sure Francis Bacon is ready for school and getting herself ready for work. She looks for her purse between the partially-consumed human corpses sprawled on the floor, wearing grotesque masks of death. Her grey legwarmers, stiff with the stuff of life and its absence, are scrunched down over her calves. She searches for her keys. Her disgusting legwarmers partially cover teeth-torn skinny black pants. What did she do with Francis Bacon’s lunch? A fingernail-shredded, knee-length, formerly-shiny silver dress hides the more lurid teeth marks in her pants. She can’t find the quarterly report. A blood-smeared, white, dress shirt collar sticks up from under a bullet-holey and knife-slashed brown cashmere sweater she’s wearing under an open knee-length black jacket. How does she misplace everything? Where does everything go?

“Look under the torso, Chi.”

Groan

“I don’t know why I don’t help you. I really don’t.”

Time passes. That’s what we tell ourselves. One minute, we’re here. The next minute, we’re somewhere else but we’re still here. What’s changed? Anything?

On my way to work, at an intersection, I watch a wild dog lope across a street perpendicular to the one I’m on. The dog’s tongue hangs out the side of its open mouth. It sees me but doesn’t change its pace. With its tail between its legs, it just keeps going. I’m part of the scenery.

I’m at the office now, sitting in a cubicle, staring at a monitor, wishing I was alive.

“Hey, Buck,” says Barry, stopping by.

“Hey, Barry.”

Barry Graves is a good-looking zombie and he knows it. He’s been shot in the face. Twice. It’s hard to tell because he’s been very well-burned. And a group of kids took shovels to his head, trying to bash out his brains—but they missed, and all they did was make him better looking. Now he’s so disfigured you can’t even make him out. His head is one big lump of rotten, burnt, dented meat. “Did you hear about Maturity Section?” he asks, leaning against my cubicle’s divider, casually.

“No.”

“Some kind of riot.”

“Really.” I’m not interested. On my way to work, I tried to think of anything I’m interested in. I couldn’t do it.

“Heads are rolling,” says Barry.

“Uh huh.”

“Hey, Buck?”

“Yeah?”

“Why is your cubicle so neat?”

That gets my attention. I keep forgetting to do things. Normal everyday things. The paper on my desk is stacked tidily. My computer is upright, turned on, and functioning. The receiver is hung up on my telephone. There are no fires. I didn’t even notice. That’s how out of it I am.

“I don’t know,” I confess. Awkwardly, I stand. I pick up the computer, hold it over my head, and crash it down onto the floor. I sweep all the paper off my desk.

“Anyway, I’ll see you later, Buck.”

“See you later, Barry.”

I try to throw a stapler through a window. It just bounces off. I look at the window: the transparency of it; the apparent fragility and the surprising strength. I pick up the stapler and try again. Same result. I do it over and over, again and again, until it’s lunchtime.

Then, in the cafeteria, I have a salad. Just a salad. Everybody looks at me. I don’t care. After lunch, I do the stapler thing some more. At three o’clock, I go to my appointment.

I don’t know how I got here. One minute I’m at work, the next minute I’m at the doctor’s office. Am I forgetting things or ignoring them?

For a while, I’m in the waiting room with the others. Then I’m in the doctor’s office all by myself. I can’t really tell the difference.

“What can I do for you?” asks the doctor, ambling in with my file.

“I don’t think there’s anything you can do for me,” I answer, honestly.

He tosses my file on his desk. “Okay then.” He falls onto a chair. “What brings you by?”

“My wife. She made the appointment.”

The doctor’s white lab coat is torn, pulled halfway off his left shoulder, and stained dark red with blood. Bits of flesh are stuck to it, here and there. “She’s worried about you, is she?” He turns away, opens my file, and pulls out a page. He turns back to me, holds up the piece of paper, and begins, methodically, shredding it into narrow strips.

“I guess.”

I look around the office: degrees have been yanked off walls; there’s shattered glass on the floor; broken picture frames have been thrown around, mindlessly, and jigsaw pieces of family photos have been strewn about, religiously. There are tongue depressors all over the place. Is that what they do here? Do they just depress our tongues? The sanitary paper that once covered the examination bed has been completely unrolled.

“Why is your wife worried about you?” asks the doctor, looking at me, interested, disinterestedly ripping what’s left of a page from my file into two last shreds that fall when he lets them go.

“I’m not eating. Not sleeping. Sometimes I cry and I don’t know why.”

The doctor stuffs his hand into his coat pocket and fumbles out a prescription pad. He snatches a pen off his desk, scribbles something down, tears off the piece of paper, crumples it, and throws it away without looking. It hits the door and falls to the floor. “Anything else?”

“I took a shower last night. With soap.”

The doctor frowns at me. His forehead doesn’t change. Neither do his eyes. He frowns at me with his mind. “Why?”

“I wanted to feel clean again.”

“Did you?”

“No. I still felt dead.”

The doctor nods. “Yeah. It’s okay.” He stands, uncoordinatedly, ambles a few steps, bends at the waist, and picks up the piece of paper he crumpled and threw at the door. “We see this sometimes.” He straightens up and stumbles back. When he gets to his desk, he kicks the lowest metal drawer as hard as he can several times. Then he falls onto his chair. “It’s not common but it happens.”

“What is it?” I’m not worried. I don’t care what he says. He could say, “Buck, you’re dying,’” and I wouldn’t care. It’d be exactly what I want but it wouldn’t make me happy. Where I am, in my head, there’s no such thing as happy. It doesn’t exist.

“You’re depressed,” says the doctor.

“I can’t be depressed.”

“You’re married, right?”

“Right.”

“Then you can be depressed.”

I stare at him, vacantly.

Vacantly, he stares back. Then he says, “That was a joke.”

“Good one.”

“Tell me about your sex life.”

“Is that another joke?”

“No.”

In my mind, I picture the last time I had sex with my wife: she wears a French maid uniform. She holds a feather duster. She waves it around in the air, half-heartedly, cleaning nothing. She won’t take it all the way. Later, she complains about how it makes her feel. She vows she’ll never do it again. It’s not open for debate.

Cleaning fetishes are among the most taboo in our community. The pornography is black-market. Underground. It’s as tame as pretty living girls in short skirts bending at the waist to pick things off the floor. Tidying up. Cute living girls in bright yellow plastic gloves washing dishes. But, from what I hear, from what I’m told, it can get pretty racy.

Before my wife told me she’d never do it again, there’s the memory of her disgusting skin where it’s exposed, beyond the uniform I ask her, no, I

beg

her to leave on. It’s so new, so clean. I keep my hands on it and my eyes on it and I try to concentrate on it. I try not to think of the truth: my wife’s open wounds and festering sores and her expressionless face as I lay on my back while she uses my rigidity, my inflexibility, my thoughtless conformity to biological processes I don’t understand and probably wouldn’t approve of even if I did, for her . . . whatever it is, amusement, or her own mindless acceptance of physiological impulses she doesn’t comprehend.

I wonder. Is this love?

“It’s not like it used to be,” I admit.

“Pretty sure you’re depressed,” says the doctor, opening and flattening the paper he crumpled a few moments ago. “I wrote you a prescription.”

“Okay.”

He crumples it back up and throws it at my face. Conveniently, it bounces onto my lap. The doctor stabs the pen into his stomach, repeatedly, until it punctures and stays there. Satisfied it will remain, the doctor, unsteadily, lifts his head. “Yeah, so get that filled, follow the directions, and you should be as good as dead. Eat some human flesh and don’t bathe or clean your clothes. You have to look after yourself, Buck.”

“Is there anything I should look out for while taking this medication?”

“The most common side effects are insomnia, loss of appetite, and sexual dysfunction.”

“So I could feel better and never know it because the side effects of this medication are exactly the same as the problems I already have.”

“Hypothetically. Why?”

“No reason.”

“Hey, you work in Reproduction Section, don’t you?”

“Yeah.”

“Are you going to make your quota?”

“Easily.”

“Good.”

Precariously, I get up. For a minute, I just stand there, wondering what I’d do right now if I weren’t depressed. Then I pick up my chair and hurl it at a filing cabinet.

“That’s it, Buck,” says the doctor. “That’s the spirit.”

When I weave my way out of the doctor’s office, I walk unevenly past all the other zombies, sitting there dumbly, staring emptily, dripping drool from the corners of their mouths. One has a machete embedded in his side, spilling white sausage from the wound. Another holds her own severed leg, dangling purple ground meat from her stump. The others reach their stiff arms out for something: death maybe, for death to return; that briefest of moments when we died, when we passed from living, actually being alive, really alive, truly alive, to just being undead. In disorganized chairs, nonaligned chairs, in chairs purposefully arranged haphazardly, in the waiting room, all the zombies sit with nearly straight bodies.

I walk outside and keep going. I walk and walk. After an hour or so, I end up on a dead-end street. There’s a chain-link fence keeping me from going any farther. Beyond the fence and through it, I see a group of living teenagers hanging out behind a strip-mall where all the deliveries are made to the backs of stores. The teenagers are gathered among big dumpsters where the day’s waste is brought out, taken away, and turned into energy to make more waste.

The teenagers are skateboarding. They’re practicing tricks on the pavement. They’re making use of the curbs, the railings, and all the other unnatural obstacles: jumping them, sliding down them, riding up, turning around, and gliding back down them. I stick my fingers into the metal diamonds and stare at the teenagers—at the life in them—through the chain-link fence. I think about their DNA. The teenagers are made of chains but they still think they’re free. Free from what? Their looks? Their brains? Their environment? The strange age into which they were born? Free to do what? Become a zombie? It’s so sad. Is there anything sadder than a slave who believes he or she is free? I don’t know. Until they get blurry in my eyes from the tears that don’t come from staring and wouldn’t come at all if I were normal, I watch the teenagers.