Zombie CSU (21 page)

However Raymond Singer, Ph.D., a nationally known expert witness on cases involving neuropsychology and neurobehavioral toxicology, says that there might be some basis for the suspension of disbelief in zombie films that have a “toxic waste contamination” plot. “It’s not a bad theory. People with this type of poisoning are alive in some senses, but dead in the finer aspects of being a human. Depending upon the case, they could go into states of automatic rage. I kinda doubt cannibalism—unless that is or was part of their culture.”

When I asked Dr. Singer to provide any examples of toxic chemicals turning someone into a soulless monster, he provided this anecdote. “I served as an expert witness in a murder trial of a confessed mass murderer, who heinously slaughtered a mother and her children while they were sleeping in their bedrooms. The prosecution wanted the death penalty—which if applied anywhere, could have been applied in this case most deservedly. After carefully reviewing the killer’s background and history in depth, and examining him personally in the maximum security facility, I concluded that his long history of exposure to toxic chemicals, including playing many idyll days as a youth in ‘Shit River’—eponymously named because of widespread pollution from toxic waste—led to the creation of a monster, a zombie, who lacked the normal human ability to control hateful impulses.

“Toxic waste and other chemicals can damage the nervous system, leading to disruptions in the ability to control, plan, manage and judge—what neuropsychologists call ‘executive function.’ In this case, his executive function failed to control his hatred for the woman and her children. Basically, he was insane and deranged, in part from toxic chemical poisoning of his youth. The jury took my words into consideration, and gave him life without parole. The killer was animated when he committed these crimes, but he had been dead inside.”

Now that’s frightening.

The Zombie Factor

In order for “toxic zombies” to work, the contamination would have to do more than alter behavior. It would have to shut down most of the body’s functions while isolating and preserving a few (minimal brain, heart, and lung activity, etc.). Toxins are dangerous, but they are not parasitic; and though contamination can be passed on, it diminishes in strength with each contact and would not be something that could be passed on through a bite. A major outbreak would require a large number of persons becoming similarly contaminated at the same time and exhibiting behavioral changes at about the same rate, which isn’t as likely. Similarities in symptomology occur more often in disease pathogens.

J

UST THE

F

ACTS

Forensic Entomology

One of the creepiest (or perhps

crawliest

) fields within evidence analysis is that of forensic entomology, which is the study of insects as they relate to police work. Many insects are necrophageous (meaning they “eat corpses”), and the study of them can help to establish the time that has elapsed since death, or the PMI (post mortem interval).

Forensic entomology is an old science, dating back to at least thirteenth-century China; however it’s become a very widely accepted science mostly over the last twenty years or so. Though there are a number of subspecialties within forensic entomology, medico-legal forensic entomology is the specialty involving the study of insects as they relate to criminal and legal matters.

A forensic entomologist is generally called in for cases where the decedent is believed to have died at least seventy-two hours ago, which is when insect presence is significantly seen and the age of newborn insects (such as maggots) from eggs laid on the body postmortem can help the entomologist begin his or her calculations. Flies typically arrive within a few minutes of death, attracted by protein-rich body fluids and to lay their eggs. They lay eggs and their maggot hatchlings feed on the necrotic tissue. As the process of decomposition kicks in, the body releases a variety of chemicals, including

putrescine

and

cadaverine

, both of which contribute to the ripe odor of decaying flesh and act as attractants to the insects that form such a necessary part of the natural breakdown of organic matter. Without this process no corpses would ever decay and we’d be hip deep in the unrotting dead. Necrophageous flies include blowflies, fleshflies, houseflies, coffin flies, sun flies, black soldier flies, and cheese flies.

Mites often come along next, feeding on the drying flesh and also dining on the fly eggs. If there are enough mites on hand and they consume a considerable portion of the fly eggs, there will be fewer maggots and, therefore, less tissue consumption, which can significantly interfere with the forensic entomologist’s attempts to estimate the normal rate of decay and hence the length of time the body has been dead. Establishing approximate time and date of death is often a crucial factor in police work.

Beetles prefer drier flesh and usually come along after the decomposition process is moderately far along. These include rove beetles, hister beetles, carrion beetles, carcass beetles, hide beetles, scarab beetles, and sap beetles.

Moths often attend the feast, dining on human hair. It’s mostly clothes moths that do this (which is something to think about next time you find one in your closet).

Other critters often found on corpses include bees, ants, and wasps. These creatures are not there to feed on the corpse but are predators who attack and eat the necrophageous insects. Just as with the mites, this can interfere with PMI calculations.

The forensic entomologist is an expert on the life cycle of these insects and by evaluating the apparent age of maggots, beetles, and mites, he or she can often make a determination of how long the body has been dead.

Expert Witness

Forensic entomologist Dr. Robert Hall, associate vice chancellor for research at the University of Missouri, discusses how the presence of these insects helps in establishing time of death: “There are two basic approaches. First is the temperature dependent development of flies (the warmer it is, the faster they develop, within limits). Knowing that blow flies arrive very soon after death, if the temperature prevailing at the crime scene can be inferred from proximate weather stations, then knowing the species of blow fly and the stage collected, it’s possible to calculate how long it would have required for the species in question to progress from the stage the female deposits on the corpse (egg or first instar larva) to the stage collected. This represents the ‘must have been dead at least as long’ estimate called the ‘minimum postmortem interval.’ The second approach is to collect all insects associated with a corpse; these ‘assemblages’ of arthropods may then be compared with decomposition studies conducted under similar environmental and geographic conditions and the time-since-death inferred from a ‘presence or absence’ analysis that refers to the aforementioned studies.”

Occasionally the type of insect can give clues to where the body might have been—as in cases where a victim is killed in one state and the body carried across state lines for burial—a tactic sometimes used by serial killers. Dr. Hall gives us an example. “Some blow fly species are found only in the far southern U.S. When a corpse is found in, say, North Dakota, and infested with a southern species, it’s pretty significant evidence that corpse was dead within the southern range of that species and subsequently transported north. Although this doesn’t happen often, it does occasionally.”

Insects don’t set up camp on a corpse by accident. They’re actually part of nature’s process of decomposition, as Dr. Hall explains. “Maggots are a powerful eating machine. ‘Maggot mass’ refers to the large number of writhing maggots that actually—by friction—generate heat above ambient temperature. These squirming maggot masses consume tissue and can disarticulate skeletons. They’re the ‘buzzards’ of the insect world.”

Maggot Therapy

For thousands of years healers (licensed or not) have used the placement of maggots on wounds as a method of preventing gangrene. Maggots will not eat healthy living tissue and will feed only on dead (necrotic) tissue. Soldiers in war would sometimes apply a poultice of maggots to a festering wound to clean it up. In more controlled circumstances, the maggots were disinfected first.

The Zombie Factor

Italian horror director Lucio Fulci (and many of his peers) was fond of using masses of maggots in his zombie flicks. In

House by the Cemetery

(1981) a zombie “bled” maggots after being stabbed. I wondered if insects would colonize a dead body that was walking around and put that question to Dr. Hall.

“I have no idea whether zombies ‘decay’ as human corpses do, but the medical condition called

myiasis

16

refers to infestation of a living body with the blow flies normally associated with corpses. Most living humans move, and thus movement itself is not a complete barrier to blow fly females laying eggs.”

This isn’t that big a stretch when you consider that humans typically wave flies away, and a zombie would be indifferent to their presence. They could very easily land and lay eggs, and the hatching maggots would have plenty of necrotic tissue upon which to feed. It would be the undead equivalent to a dinner cruise, or maybe an ambulatory “meals on wheels.”

T

HE

F

INAL

V

ERDICT

: T

HE

C

RIME

S

CENE

I

NVESTIGATORS

The amount of information that can be collected is amazing, and all that the forensic investigators can glean from that evidence is truly staggering. Because we live in a computer age and the Internet is a reality of our lives, investigators can share information via databases and e-mail, they can instantly contact with other experts around the world, and they can bring to bear such a weight of technology that our poor mindless zombies don’t seem to have much of a chance.

Fingerprints, blood analysis, bite mark analysis, forensic art and anthropology, toxicology and entomology, footprints, and gait patterns…any one of these elements might identify our patient zero and help investigators backtrack to a possible source of contagion while at the same time hunting down the zombie/vector.

This is an area seldom if ever addressed in zombie fiction, as if there would be no time to use forensics and nothing to be gained even if there was time. Slow, shuffling zombies are just not going to move faster than science geeks. Not going to happen.

Medical Science Examines the Living Dead

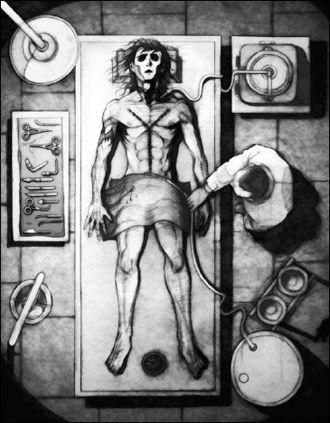

Zombie Autopsy

by Zach McCain

S

cience cannot exist in the absence of logic. Science depends on both theory and evidence. If the recent dead came back to life, there must be a reason, and that reason will have to be grounded in science.

In

Night of the Living Dead

Romero insists that “something” has caused all the recent human dead to return to life. He includes in this buried corpses, subjects of autopsies, accident victims—the works. Whereas this is extremely cool and cinematically very threatening, it makes no scientific sense at all. In order for humans to move, certain parts of the central nervous system

have

to be working. Any other explanation is magic, and Romero never intended his films to be supernatural.

So, we’re going to make a couple of deductions. First, if the dead rose, then this would have to be the result of some kind of pathogen. No other explanation really stands up to scientific scrutiny. Epidemics start from a source, are spread by a vector, and then increase exponentially as long as the vector(s) continue to make infectious contact with victims.

In later films and books of the genre, the other storytellers recognized the logical need to address this and established that the plague is spread through direct infection, specifically through the exchange of fluids during a bite. And this is necessary in order for the films and books to continue to be frightening, and indeed to become even more frightening. Otherwise it’s fantasy, and we’re much too jaded these days to get spooked by something that has no possibility of ever coming true. We need at least some measure of plausibility.

The burden is on the filmmakers and authors to create a framework on which a plausible story can be built. Throw the audience a bit of a bone, logic-wise, and they’ll allow for a lot; insult the intelligence of an audience by denying them

any

reasonable scientific structure, and their mood gets ugly real fast. And I don’t blame them one bit. There are whole books written on the inaccuracies in classic and beloved shows like

Star Trek, The X-Files, Buffy

…and online message boards are ablaze with postings about everything from continuity errors (like Han Solo’s now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t vest in

Empire Strikes Back

), to technical flubs (the entire crew leaving the

Sulaco

to go down to the planet in the film

Aliens

), to outright scientific impossibilities (

Daredevil

doing gymnastics and intense fighting after having been stabbed through the shoulder—he has heightened senses, not a mutant healing factor!).

1

Most monsters can be scientifically understood, at least to some degree. Werewolfism—overactive hair follicles notwithstanding—has been heavily documented, particularly in court cases involving a person tried for werewolf murders. Anyone who understands abnormal psychology and who reads the many transcripts of those trials will see a clear pathology indicating sociopathic behavior. What the courts called a “werewolf” four hundred years ago would very clearly be called a serial killer today.

The legends of a mysterious invisible night-predator sneaking into the bedrooms of children by night and stealing their breath is what our ancestors called vampires but which we call sudden infant death syndrome. The belief of a soul-stealing old hag who comes in the night to torture men is now understood as sleep paralysis. Granted, not all the things that go bump in the night have been (so far) explained away, but someone grounded in science and using an open mind can work up a really good set of explanations for

most

of them.

2

Zombies, though they are creatures of fiction rather than folklore, can also be reasonably understood. Except for a twitch here and there, Romero did a solid job of giving us a set of guidelines to understand the zombies. He is a very smart man and a terrific storyteller, and though he’s not a scientist, he did try to make sure scientific plausibility existed within the framework of his undead world. In his films it’s established that:

Zombies are not alive. They are the recent dead brought back to some kind of semblance of life, but they are definitely corpses.

Zombies are not alive. They are the recent dead brought back to some kind of semblance of life, but they are definitely corpses. Zombies don’t breathe. Maybe some of them have been shown to have throats torn away, gaping chest-cavity wounds, etc.

Zombies don’t breathe. Maybe some of them have been shown to have throats torn away, gaping chest-cavity wounds, etc. Zombies don’t think. Not (at least) until the third movie, and then more so in the fourth. This suggests that a process of change is ongoing in the zombies and that cognitive powers may be returning to them.

Zombies don’t think. Not (at least) until the third movie, and then more so in the fourth. This suggests that a process of change is ongoing in the zombies and that cognitive powers may be returning to them. Zombies can’t be wounded (only killed). Lop an arm off, riddle their bodies with bullets and you get bupkiss. Put a round through the brainpan and the ghoul goes down.

Zombies can’t be wounded (only killed). Lop an arm off, riddle their bodies with bullets and you get bupkiss. Put a round through the brainpan and the ghoul goes down. Zombies can be killed only by severe trauma to the brain. This suggests that the central nervous system functions to some degree.

Zombies can be killed only by severe trauma to the brain. This suggests that the central nervous system functions to some degree.

For this chapter I approached a number of experts in various medical and scientific fields to see if we can get a better scientific view of what zombies are and what makes them do what they do.

J

UST THE

F

ACTS

Neurology and the Living Dead

The first problem to solve is: Are zombies truly dead, partly alive, or something else? Personally, I’m leaning toward “something else,” some state between clinical death and actual life.

Let’s discuss death. It’s not just an end to life—which is both a medical and philosophic issue—death is also a process during which the body undergoes remarkable change. The dead are by no means static, they’re not frozen in time. Death begins the instant the heart stops beating. Without blood flow no oxygen goes to the cells. The brain cells are one of the first to die in the absence of oxygen, and the skin cells are among the last. Depending on temperature, the presence of insects, and other factors, this process may occur at different speeds. When the heart stops beating, blood no longer flows and begins to settle, draining from the highest points to the lowest point due to gravity. The upper skin surface is pale as blood drains, and the lower parts of the body darken as that blood collects. The now inert cells no longer produce the molecular movement needed to energize the biochemical processes in the muscles. Calcium ions leak into the nonenergetic muscle tissue and prevent them from relaxing normally, and therefore stiffen. This muscular rigidity is called rigor mortis and it kicks in about three hours after death and will keep the body as stiff as a statue for about thirty-six hours. As more and more cells die, the body’s capacity to fight off destructive bacteria fails; and then the enzymes in the muscles, coupled with the now uncontrolled bacteria, begin to decompose the muscles, which ultimately cause the muscle integrity to fail, and the body becomes limp again.

During this time the body’s temperature steadily cools. On average it takes about twelve hours for a corpse to become “cool” to the touch; and a full day for it to cool all the way to the core.

Are zombies dead? Do they fit the criteria? If we take the Romero zombies as the basis for our discussion, we have to assume that some aspects of reported zombie behavior must be dismissed. For starters, there is no way an embalmed corpse will rise. Nope, no way. I’m going to mark that down to bad reportage from hysterical and therefore unreliable witnesses.

I posed the question of zombie reanimation to my experts. They weren’t as dismissive of the whole idea as you might think. In fact, they collectively built a pretty strong case for how a zombie might operate. Strong enough to be deliciously creepy.

Let’s start by discussing the anatomy and function of the human brain, which is essentially an electrical and chemical machine, weighing only three pounds and containing about 100 billion cells. Most of these cells are called neurons and serve basically as on/off switches to conduct electrical impulses. Neurons are either transmitting signals (on) or resting (off). Each neuron has a cell body, a kind of conducting wire called an axon, and a pump for shooting out neurotransmitters that cross a gap between neurons (called a synapse) and are received by a receptor (called a dendrite), where the neurotransmitter triggers the next neuron to continue sending the signal. Different neurons use different types of transmitters, including epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine and others. Collectively, the electrical charge from these billions of axons generates a charge equal to a 60-watt lightbulb (give or take). Devices such as the electroencephalograph (EEG) can track and measure this electrical activity.