Zionism: The Real Enemy of the Jews, Volume 1 (8 page)

Read Zionism: The Real Enemy of the Jews, Volume 1 Online

Authors: Alan Hart

Because real understanding is impossible without reference to some of the major events of the 20th century, the context includes: two World Wars; the revolution in Russia that ended a thousand years of monarchy and brought the Communists to power; and the superpower rivalry that followed, including the obscenity of the arms race (obscene because it gobbled up the money and other resources including brainpower that, in a more civilised and sane world, would have been committed to fighting and winning the only war that matters—the war against global poverty in all of its manifestations).

In my experience one way to keep focused on the main issues raised by the telling of a very dramatic, exciting but complicated story is to have in mind one key question, and to go on asking it as the events unfold. The key question in my mind as I researched and wrote this book was:

Did two events—Imperial Britain’s decision in 1917 to give Zionism a spurious degree of legitimacy and the obscenity of the Nazi holocaust— make it inevitable that the story of Zionism’s colonial enterprise would have only an apocalyptic ending?

When I reviewed the final draft of my manuscript for this book, I took some comfort in the fact that I had performed in accordance with the first rule of journalism. It states that if the reporter offends both or all parties to a dispute or conflict, he (or she) is probably on the right track. I set out, not to give offence for the hell of it, but to participate in seeking the resolution of this dreadful conflict, for the well being of all concerned. Nonetheless, this book will offend not only Zionists everywhere and their standard bearers in the mainstream media, but also many in the political Establishments of just about the whole world, the Western and so-called democratic world especially but also the Arab world. (It’s impossible to tell the truth about Zionism without also telling the truth about the impotence of the Arab regimes). But I do believe this book should not give lasting offence to any who really want a just and sustainable peace because my real purpose, contrary to what sometimes might appear to be the case, is not to blame but to explain.

For Jewish readers especially I want to quote the most honest statement ever made to me by an Israeli.

He is the Israeli I most respect and admire. When I talked about him in the major capitals of the world to diplomats with the prime responsibility for crisis managing the Middle East, I said that if I was putting together a world government with 20 portfolios, he would have several of them, on account of his experience, his intellect, his wisdom and his humanity. In private conversations with me he did not display even a hint of the insufferable self-righteousness that is the hallmark of Zionism. He is without arrogance. For about two decades he was the head of research at the Directorate of Military Intelligence. Then, in 1973, he was called upon to become DMI, with a brief to make sure there could never again be an intelligence failure of the kind that had occurred in the countdown to the Yom Kippur war. He was, in short, the man to whom the government of Israel turned for salvation in the aftermath of what it perceived at the time, wrongly, to be a real threat to the Zionist state’s existence. His name is Gazit. Shlomo Gazit. Major General (now retired) Shlomo Gazit. I met him while I was shuttling to and fro between Peres and Arafat. In our little conspiracy for peace, Shlomo was one of the chosen few advising Peres.

Over coffee one morning I took a deep breath and said to Shlomo: “I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s all a myth. Israel’s existence has never ever been in danger.”

Through a sad smile he replied, “The trouble with us Israelis is that we’ve become the victims of our own propaganda.”

If this book assists Jews everywhere to come to terms with that truth and its implications, I shall be—forgive the cliché—all the way over the moon. Because that would make real peace possible.

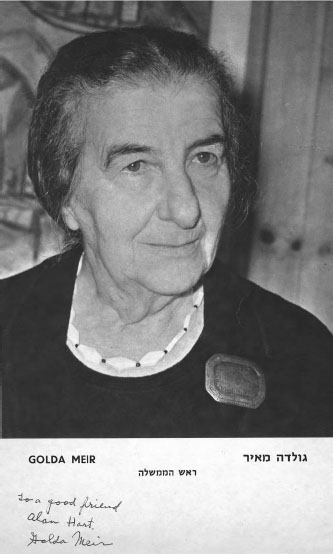

On reflection I decided that the cause of understanding might be well served if I reveal Golda’s last private message to me. It was in the form of a confession. With poetic license I could call it a deathbed confession. And it has its place in Chapter One.

A VOICE FROM THE GRAVE

When Golda Meir died at 4.30 p.m. on Friday 8 December 1978, she was three years older than the 20th century. She had been one of the movers of the wheels of history for the best part of six decades.

Within minutes of hearing the news on the radio I booked a flight to Israel. On this occasion I went as a private citizen representing nobody but myself, with a simple wish to pay my last respects to a Jewish friend as she was lowered into her grave.

On arrival a telephone call to Lou Kaddar guaranteed that I would receive the necessary security clearance to attend the burial at the national cemetery on Jerusalem’s Mount Herzl.

Lou was a warm, witty, wonderful Jewish lady of French origin. She had been Golda’s assistant, most trusted confidant and best friend for more years than either of them cared to remember. When Golda was prime minister, Lou handled the men in her cabinets according to need. Sometimes as equals. Sometimes as children.

Golda was to be buried in a plot next to her predecessor as prime minister, the wise but much maligned Levi Eshkol. (As we shall see, Eshkol had not wanted to take his country to war in 1967, which was why he was maligned by those then called “hawks” in Israel).

The final farewell to Golda on Mount Herzl was going to be brief. Golda herself had seen to that. When she was very much alive she had deposited a sealed letter with the administrator of the Labour party, with the instruction that it should not be opened until she was dead. In the letter Golda said she wanted no eulogies at her graveside. When later she informed some of her senior Labour party colleagues of the contents of the sealed letter, she said, “When you’re dead, people often say the opposite of what they mean about you.” In life she could not bear the thought of somebody like Begin adding to his own prestige by basking at her graveside in the light of her achievements. When she died Begin’s government considered her request and decided to respect her wishes.

It was, in fact, in my

Panorama

profile of her that Golda had put her nation on notice that she wanted no fuss when she died. Early in our friendship Golda told me she had no intention, ever, of writing a book about her life, in part because she had never kept a diary. She had been too busy for that. I said there had to be a record of some sort in her own words because she had played a role in shaping the history of the world. My last question to Golda for my profile was about how she wanted to be remembered. She replied that she didn’t want any streets or buildings named after her, and she didn’t want any eulogies at her funeral. Then, after a pause, she said she had just one wish: “To live only as long as my mind is sound.”

1

Her fear was not of death but life as a cabbage.

In truth there was no need for eulogies. For Israelis of her own generation Golda’s record of achievement spoke for itself.

The sobriquet “Mother Israel” was appropriate on account of her achievement in the months before the birth of Israel. Without what Golda achieved on a fund-raising mission to America, the Zionist state-in-the- making would not have acquired the weapons to give its leadership the confidence to declare their independence and trigger a war with the Arabs; and the Zionist enterprise might well have been doomed to failure.

On 29 November 1947, the consequence of Britain wanting to give up and get out of Palestine in the face of an escalating confrontation between its indigenous Arab inhabitants and incoming Zionist settlers, and a Zionist campaign of terror against the occupying British as well as the indigenous Arabs, the General Assembly of the United Nations voted to partition Palestine. There was to be one state for the Arabs and one for the Jews. The Arabs rejected partition but, as we shall see in Chapter Ten, the UN vote was rigged and the partition decision could not be implemented. So far as the UN was concerned as the body representing the will of the organised international community, the question of what to do about Palestine was still without an answer. But the British occupation of Palestine was going to end at midnight on 14th May 1948, whatever the situation at the UN and on the ground in the Holy Land. The mess the British had created would have to be cleared up by the UN (the successor of the ill-fated League of Nations), if it could be cleared up.

As soon as the British were gone, the Jewish Agency, the Zionist government-in-waiting, was intending to declare the coming into being of the Zionist state. The problem was that the Jewish Agency’s official underground army—the Haganah ostensibly for defence and the Palmach for attack—lacked the equipment and the ammunition to fight and win the war its unilateral declaration of independence would provoke.

The Jewish Agency’s treasurer, Eliezer Kaplan, made a presentation to the Agency’s Executive Committee, the Cabinet-in-waiting. Kaplan estimated they needed a minimum of $25 million U.S. dollars to equip the Haganah and the Palmach for war with the Arabs. The most urgent need was for tanks and planes. The only place where serious money could be raised was America. But Kaplan had just returned from there. His news could hardly have been more gloomy. American Jews, he pointed out, had been “giving and giving since the beginning of the Hitler era”. Because of that and the fact that wartime prosperity had come to an end in America, there was not so much money around. As a consequence there were limits to what they could expect to raise from America’s Jews. He estimated that perhaps $5 million, certainly not more than $7 million, could be raised in America. And that was not nearly enough to guarantee the survival of their state when they declared it.

David Ben-Gurion, the leader of the Jewish Agency and prime minister in-waiting, was an irascible character at the best of times. As Kaplan was sitting down, Ben-Gurion leapt to his feet. “I’ll leave at once for the United States.” Raising money was obviously the most immediate and most essential job. As leader he had to be the one to undertake the mission. Only he was likely to be successful. He did not say so but that was his view.

Golda at the time was the acting head of the Agency’s Political Department. She spoke her mind. When she was recalling the moment, she told me that even she herself was surprised by the words that came out of her mouth. “Let me go instead,” she heard herself saying. “Nobody can take your place here. What you can do here, I can’t do. But what you can do in the States, I can do.”

None too politely Ben-Gurion rejected Golda’s suggestion. But she was not going to take “No” for an answer.

“Why don’t we let the Executive vote on it?” Golda said.

With some reluctance Ben-Gurion agreed and the Executive voted for Golda to go.

“But at once,” Ben-Gurion said. “You must go immediately.”

She was driven to the airport in the spring frock she had put on for the Executive meeting and without a coat for the bitter winter that would greet her on arrival in New York. Her only luggage was in her handbag. It contained a ten-dollar bill and her comfort—her cigarettes. She smoked up to three packets a day.

Only when she was in the air did she allow herself to think about the consequences of failure. She was terrified by the thought that she might have bitten off more than she could chew. What if Kaplan was right in his assessment that America’s Jews would come up with not more than $7 million or less?

Golda was no stranger to America. She was born Goldie Mabovitch, the daughter of a carpenter, in Kiev, in the Ukraine. In 1906, when she was eight, the Mabovitch family emigrated to America and took up residence in Milwaukee.

She received her very first lesson in American politics and how it really worked on a visit to the home of Joseph Kennedy. He was bouncing his first-born son on his knee. Suddenly he lifted the boy into the air like a trophy. Then, sure that he had the complete attention of his audience, he said, according to what Golda told me, “It might take 50 million dollars, but this boy, my boy, will one day be the President of these United States of America and live in the White House.”

2

(As it happened Joe Kennedy’s first son did not make it. He was killed in action in World War II. But the second son, John Fitzgerald, did go all the way to the White House where he lived for a thousand days before his assassination).

The first great test of Golda’s ability as a major fundraiser came in Chicago on 21 January 1948, at a meeting of the General Assembly of the Council of Jewish Federations and Welfare Funds. All the delegates were professional fundraisers. They controlled the Jewish fundraising machinery across America. Because of Golda’s speed there had been no time to prepare the way for her. She learned about the meeting only after her arrival in America. Her first task was to persuade its organisers to let her address the gathering. Palestine was not on the agenda and most of the delegates had never heard of Golda Mabovitch. She was, so to speak, an unknown, cold calling. When she rose to speak she was aware that most of the elderly fundraisers in her audience were not supporters of the Zionist cause. Some of her friends in New York had advised her not to address this particular gathering because she might find herself in confrontation with those who opposed Zionism.