Zero Hour (14 page)

With the nearest pillboxes captured, the 4th Division stacked the dead outside and used the blockhouses as headquarters, first-aid posts or resting places, while the dead men's skin blackened under the hot sun. Only one part of the line hadn't been captured, and, as the men dug in, German machine-gunners fired in the distance. The Australians launched several more futile charges. In one, Lieutenant Thomas McIntyre knew he couldn't fulfil his orders to capture a pillboxâit hadn't been hit by a single shell. All he said was, âAlright Sir, if it is to be taken it will be taken.' When he led his men over the top, he was killed alongside them.

Several days later, the Germans withdrew. Over 7500 men had been taken prisoner and all objectives captured. The battle had been so successful that many troops wanted to push on and capture the German guns that began shelling the new Allied trenches, but Plumer preferred small advances, to prevent the troops becoming too exhausted to defend their position.

Within 48 hours, long mule trains were transporting hot food and tea up to yet another front-line trench the men had dug. With so much digging in, the New Zealanders and Australians were now referring to themselves as âDiggers'.

HUMAN LIKE US

Before burying the dead, the men searched them for letters to loved ones, diaries, or other things of value to be sent home. They also hunted through German pockets for letters and photos either to keep as souvenirs or so they could be returned to the soldier's family. Lance Corporal Bett felt that

Somehow we get wrong ideas, we forget the Hun is human like us, has his home, his loved ones and sweethearts, and it was pathetic to look through the private belongings of the Huns we buried, and see his photos, and little Bible and treasures.

To many Australians and New Zealanders, the German was a âBoche', a âHun', a âFritz', an enemy they rarely sawâit was âold Fritz' that sent over shells or fired SOS rockets or was shot. The Diggers were eager to punish them for starting the war and for the atrocities they'd committed. They wanted, as Captain Harold Armitage wrote, to âmake our names stand out in Hunnish blood'. Some wanted nothing more than to use their bayonets on them. When Private David Harford first killed a German

a queer thrill shot through me, it was a different feeling to that which I had when I shot my first Kangaroo when I was a boy. For an instant I felt sick and faint, but the feeling soon passed; and I was normal and looking for more shots.

Similarly, Sergeant Eric Evans âfelt little emotion, just intense excitement'. Even after battles, men itched âfor another smack at the rotten Hun'.

Time allowed some soldiers to reflect on their actions and their beliefs about the âenemy'. Second Lieutenant Simon Fraser recalled how everyone cheered when their artillery smashed in German trenches,

but one does not think till afterwards that some poor devils may be flying up with it, who are just as anxious for the war to end as we are.

Private John Wright came to see them as ordinary men, like himself: âI don't think old Fritz is any better or worse than our soldiers.' And when Evans saw a mixture of German and Allied dead, he felt that it no longer mattered which side they were on. âThey are dead, and for their loved ones, that is all that matters.'

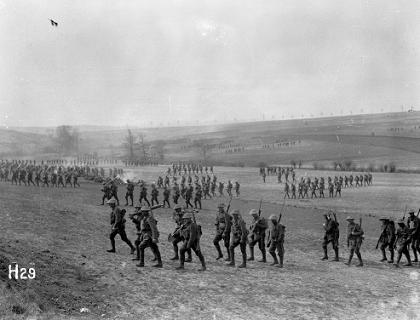

New Zealand troops training for an attack on Messines, Belgium.

Alexander Turnbull Library G- 12753-1/2

Like the Australians and New Zealanders, the Germans volunteered to defend their country and for adventure. One soldier, 19-year-old Ernst Jünger, volunteered on the first day of the war and marched out âin a rain of flowers' from well-wishers. After growing up âin an age of security, we shared a yearning for dangerâ¦We thought of it as manlyâ¦Anything to participate, not to have to stay at home.'

In the trenches, the Germans faced the same conditions as the Allies. They stamped their feet for warmth, used helmets as basins to wash in and, when it was quiet, thought of home. They too grew quiet as they marched forward through shell storms. They buried and mourned their dead and accepted cigarettes and bars of chocolate offered to them by captured soldiers. From craters, they watched and listened to low-flying aeroplanes circling âvulture-like' overhead, emitting âa series of low long-drawn-out siren tones' to alert their artillery. More often than not, shells would follow. During battles the men knew that if they fell, they'd be left to dieâa fellow soldier told Jünger that âNo one can help⦠Everyone knows this is about life or death.'

THE SOUR SMELL OF NEW DEATH

Within days, the New Zealanders and the 3rd Division began patrolling closer to the Warneton Line, the third line of German defence that had become the Germans' new frontline. In the dark, they bombed fortified strong points set up in farm ruins and craters. At dawn, the front-line troops returned to newly set up posts in shell holes and pulled over camouflage netting to prevent aeroplanes from finding them. It was dangerous work, and the German machine-gunners were active. New Zealander Private Sidney âStan' Stan-field saw his mate Private James Hallett, a shepherd from Waipukurau, get shot as they moved out of a trench. He recalled when he returned the following day to bury him,

poor old Jim was laying there, cuddled up in a heap, as men die. Don't forget we were all young, we didn't die easy. You don't die at once, you're not shot and killed stone dead. We were fit and highly trained, and of course we didn't die easy. You were slow to die, and you'd find them huddled up in a heap like kids gone to sleep, you know; cuddled up dead.

It had been hoped that the Germans would withdraw, but instead they strengthened their posts as their artillery tore into the Allied trenches and gassed and bombed the areas behind. Lieutenant George Mitchell saw a single shell kill seven men, leaving only shattered remains. The air stank of hot blood: âthe sour smell of new death, mingled with the hated acid of high explosive.' From a distance, machine-gunners fired at the men. An Australian officer who was new to the line asked Mitchell to knock out a troublesome machine gun, saying, âYou've got a decoration. How about you going out and silencing it?' Mitchell replied, after some thought, âHow about you going out and capturing it. Then you'll have a decoration too.' Neither went out.

Where possible, the men slept in the safety of captured German dugouts and pillboxes. With each close shell-burst the pillboxes would ring and rock. At times, only the âoccasional cry of “Stretcher-bearers!” broke the horrific monotony of whirring and crashing shells'.

In July, Mitchell was woken by a series of shell explosions. Then the daylight streaming into the entrance was blocked by his skipper, stumbling down the stairs, saying, âI'm hit.' His voice filled Mitchell with a âdragging, cold dread'. The officer had been trying to move men to safety when a tiny piece of shrapnel had pierced his chest. With each pulse, blood spurted from the wound. The officer, knowing he was dying, kept saying âI'm done, I'm done.' Mitchell knew he couldn't help him but he still tried to stem the blood. Tears fell down his face. There was nothing he could say to comfort him. Blood gurgled into the officer's chest. âSay good-bye to the boys. Tell my wifeâ' he started, before saying a prayer.

After the officer died, Mitchell climbed back into bed and slept. It was all he could do. It was what he had to do to survive at the front.

KILLED IN ACTION

____________________

CAPTAIN HAROLD ARMITAGE

School teacher. 3 April 1917

SECOND LIEUTENANT SIMON FRASER

Farmer. 11 May 1917

PRIVATE JAMES HALLETT

Shepherd. 8 June 1917

LIEUTENANT THOMAS MCINTYRE

Carpenter. 10 June 1917

PRIVATE MATTHEW GRAY

Miner. 12 October 1917

DIED OF WOUNDS

____________________

PRIVATE DAVID HARFORD

Miner. 31 March 1917

LANCE CORPORAL ROBERT BETT

Coachbuilder. 15 June 1917

SAPPER EDWARD EARL

Labourer. 28 July 1917

CHAPTER NINE

THIRD BATTLE OF YPRES, 1917

THOUGHTS

I'm travelling down a long straight road,

In Flanders, here in Flanders.

It's mud and cobbles, and cobbles in mud,

In Flanders, here in Flanders.

Tho' some may say that fine it beâ

A soldier's life is not meant for me,

For it's naught but cobbles and mud, you see,

In Flanders, here in Flanders.

TRUMPETER HERBERT AUBURN

ON 22 JULY, with the lower Messines ridgeline captured, over 3000 British guns began saturating the Ypres heights in preparation for Field Marshal Haig's main offensive to force the Germans from the high ground. Through a series of advances, British troops were to extend the line eight kilometres to Passchendaele.

To create a diversion, II Anzac Corps prepared to attack the Warneton Line, 10 kilometres from Ypres, but the Germans, watching the preparations from the heights, knew where the real advance was going to come from.

On 31 July, the first advance beganâto Pilckem Ridgeâ but the right flank of the British troops' 27-kilometre front was stopped at Menin Road by machine-gun fire between the shattered remains of two woodlandsâInverness Copse and Glencorse Wood. Then rain began falling: the heaviest downpour in 75 years. The complex drainage systems of the low-lying Flanders area had been destroyed by the war, and the rains quickly turned the land into a sea of mud. Orders were given to halt the attack.

Two hours after the British advanced, II Anzac Corps attacked the Warneton Line. Two battalions of the 3rd Division charged outposts while the New Zealanders fought from house to house in La Basse Ville. Then the rain blew in from Ypres.

The battlefield from La Basse Ville to Ypres became a bog. Men stood with their backs to trench walls, coats sodden and filthy, their wet socks and boots sinking into the mud.

HOPE DRIES UP

In the following weeks, further attacks over the churned mud and flooded craters failed to seize the woods. By the end of August the British held only the edge of Inverness Copseâ through harsh fighting it had changed hands 18 times. Haig, who'd believed that the Germans were demoralised, had abandoned General Plumer's small advances in favour of deeper ones, but now it was British morale that was suffering. One captured British soldier said he'd gladly shoot the officers who'd ordered the attacks.

Haig was determined to continue so, with Plumer in charge, a new offensive beginning on 20 September was planned to capture the centre of the Ypres heights. The area around Menin Road and the two woods was the first objectiveâan advance of 1300 metres in three short stagesâthen, further along the ridge, Polygon Wood and Broodseinde. From there, two more advances would see Passchendaele captured and the German line possibly broken. With the British divisions exhausted, the 1st, 2nd and 5th Australian Divisions of I Anzac Corps moved to Ypres after a long period of resting and training. The 4th Australian Division, which had fought with II Anzac Corps at Messines, was also back with the corps.

MENIN ROAD

In the darkness of 20 September, the 1st and 2nd Divisions, fighting side by side for the first time, huddled close to Inverness Copse and Glencorse Wood. Once leafy and beautiful, the woods were now black and skeletal against the skyline. The men were on the southern part of the ridge, and to their right was Menin Road, which ran from Ypres to Menin. Flares revealed shadowy pillboxes in the distance. Zero hour, 5.40 a.m., was close. The Australians readied themselves, then, with British divisions on either side, they advanced.

For five days, the artillery had bombarded the now-dry land with 1.5 million shells. It had crushed the fighting spirit of the Germans; many emerged from pillboxes waving white cloths as the Australians charged. The first and second stages fell quickly, and with the shattered woods in their hands, the men waited in captured pillboxes or shell holes, eating sandwiches, smoking German cigars and even reading newspapers.

One Australian group in a pillbox was surprised by a German messenger dog. In a metal tube tied to its neck was an order for the men who should have been in the pillbox to immediately recapture the lost land. But they were dead, wounded or prisoners helping to stretcher out the wounded. Their comrades further back were then expected to retake the land, but they had to advance through a storm of shells and no counterattack reached the Australians.

At the end of the third stage, the troops dug in as shells exploded around them. The men were in high spirits: the attack had been quick, limited and successful across the 12-kilometre front. They were relieved from the front-line that night.

Still, over 5000 Australians had been killed or wounded, most as they dug in. In this battle, as in others, families lost more than one son or brother. The Seabrook family of Five Dock in Sydney received three telegrams afterwards, one for each son that fought beside Menin Road. Theo was 25, George, 24 and William, 21. It had been their first battle. The bodies of Theo and George were never found. William, who was mortally wounded and died the following day, was buried nearby. It was devastating news for their parents and their youngest brother would never speak about it in his lifetime.