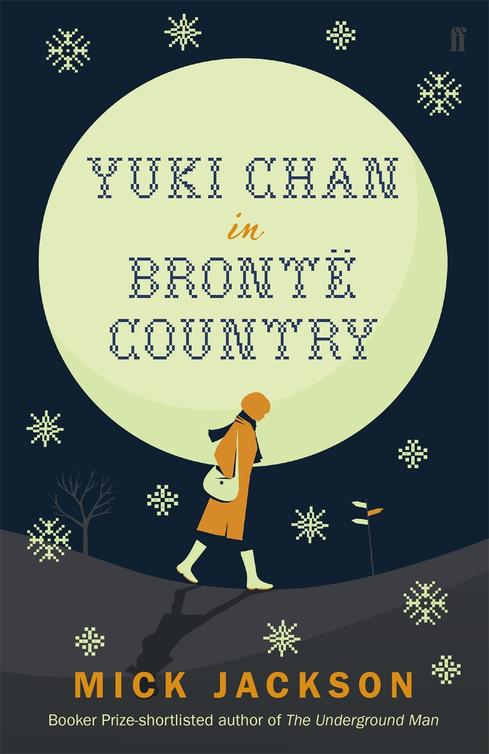

Yuki chan in Brontë Country

Read Yuki chan in Brontë Country Online

Authors: Mick Jackson

MICK JACKSON

Y

our only hope of getting a half-decent photo of the Post Office Tower is to shoot it from a distance. You can try standing directly below it, but the concrete base just gets in the way. There may be something in between these two perspectives, but Yukiko couldn’t find it. Which is kind of odd, since she’s long considered the Post Office Tower to be as much an icon of her beloved Swinging Sixties as Biba, The Beatles and Mary Quant.

Of course, the one surefire way of getting a great picture would be to rent a helicopter and hover over it, just off to one side. That way you’d get the height as well as the detail. Like those shots of Apollo 11, when it’s sitting on the tarmac in the last few seconds before they put a match to a billion litres of rocket fuel to try and get that sucker off the ground.

It didn’t take long for Yuki’s sister, Kumiko, to set her straight regarding any hope of her actually going up the tower. Apparently, civilians haven’t been allowed anywhere near it since about 1972. So not only is there no easy way of taking a photograph, but you can’t get inside to admire all the fittings and fixtures, or take an elevator up to a viewing platform – if such a thing even exists.

There’s a whole bunch of reasons why Yuki has such affection for the Post Office Tower, relating to its own peculiar beauty and the period in which it was conceived, but her Number One reason is the fact that it has one of the original revolving restaurants. Yuki gets giddy just thinking about it. Back in ’69 it must have seemed like the height of sophistication to be sitting at a table eating your fancy Sixties food while the world eased slowly by you – and presumably at exactly the right speed. Because too fast and you’d be bringing up the food you’d just eaten, and too slow and you’d have finished your meal and be back in the elevator before you’d covered the full 360 degrees. Someone somewhere must have carried out research into the optimum speed of revolving restaurants. When Yuki opens her Museum of Interesting Things she plans to make it a priority to track down all those technical drawings and data and have them displayed in pride of place.

Anyway, the fact that the restaurant hasn’t moved in several decades is, in Yukiko’s opinion, pretty much an International Tragedy. Not least, since high-altitude revolving restaurants now seem to be just about everywhere. The old Post Office Tower could show some of these new kids how it’s meant to be done. Yuki has put some thought into how she might sneak up there and get it going. Rather than waste time trying to crawl in through the air-con or sewage system, she’s decided the trick is to just show up with a dozen or so like-minded comrades, all dressed in their Sixties skirts and frilly

blouses, with their Vidal Sassoon haircuts, giggling and carrying bottles of champagne – as if they’ve just emerged from their own little time machine. Then just swan right past the security guy, stumble into the elevator, and – still giggling – zip on up to whatever floor the restaurant’s on.

It might take a little while to locate the light switches, and a little while longer to get the thing moving again. Yuki likes to imagine there’s just some great big lever. Then that old turntable will slowly grind back into action, and she and her pals will take their snacks out of their handbags and have a little picnic, gazing out over the city, pretending that it’s 1969 down there.

In fact, having encountered the tower up close, Yuki now sees that it’s not so much a NASA rocket and more a space station, with all its components neatly docked together and the whole thing planted just south of Regent’s Park. And she’s begun to wonder if there’s not some way of running giant cables between all the world’s revolving restaurants, with little chairs hanging off them, like on the ski-lifts. In the Beautiful Decrepit Future this may be the only means of international travel: sitting in a plastic seat, creeping high above the silent cities, as the revolving restaurants are cranked by hand.

Queues of people will fill the stairs, all patiently waiting for their long, slow journeys. People will be too tired, too philosophical to fight. In the past, the curvature of the earth might have been an issue, but the height of these new skyscrapers should see to that.

As you creep through the cold, still air on your plastic seat you’ll occasionally pass couples coming the other way. How’re things in Budapest? you’ll say. How many days’ travel is it from here? And it’ll be so good to see a fellow human you’ll find yourself longing to reach out and touch them. But the closest they’ll come to you will be fifty metres or so. You’ll watch them slowly pass. Then you’ll both carry on in different directions. And you’ll keep on looking back over your shoulder, until they’re just tiny specks of people, then finally gone.

Y

ukiko sleeps. She can’t seem to help it. She only has to take a seat or stretch out on a hotel bed these days and she’s out, like a boxer hitting the deck. And the next thing she’s coming round, all weak and sickly, and even more exhausted than she was before. At night, in its allotted hours, her sleep is fitful, unproductive. She wonders if maybe some unidentified gland fails to spit the appropriate dose of something important into her bloodstream. Or perhaps it is the English air.

Of course, she’s still burnt out after the last few months of college. Plus her internal clock has yet to align itself to UK Time. Then there was the flight itself. Twelve solid hours of inertia, breathing all that depleted air. Isn’t there legislation, she thinks, that limits the number of years a flight attendant can work before they’re grounded? Something happens. A thickening of the ankles, or constriction of the blood vessels in the brain. Then there were the late nights out with her sister before coming up here. Yuki doesn’t usually drink that much, but everyone else seemed to be throwing it down their throats with such grim determination. Including her sister. Who never used to drink at all.

She opens her eyes and has a quick glance round the coach to see if anyone’s noticed she was sleeping. Across the aisle, Mrs Kudo sits and stares out the window, watching the West Yorkshire moors roll by, apparently enthralled. Yuki’s talked to her two or three times and found her to be perfectly pleasant. Her only problem is that, along with every other woman on the coach, she’s a clear forty years Yuki’s senior.

She checks her phone for messages, then opens up her notebook. She’s kept a notebook since she was twelve – for her sketches, plus any odd little observations/hare-brained ideas. It is currently the place to note down anything idiosyncratically English. She is an anthropologist! For example, the tendency for English couples to argue in the street, regarding the most personal matters. Household finances … rumours of possible infidelities. Sure, they’re

drunk

, but even so.

She is like Columbo, gathering evidence. Imagines herself in grubby grey macintosh shambling around the streets of England, taking it all in. She will be mocked, naturally. Oh, that scruffy, bumbling Japanese girl! So ignorant of local custom. What an utter buffoon. Until at last she shuffles on up to the blondest, best-dressed suspect (in the most prosaic possible surroundings – their kitchen, say, or the drive to their expensive-looking house) and with notebook open, slightly cross-eyed, she scratches her head and throws one hand up into the air. And with a few choice words reveals the inconsistencies in their story, their motive, along with some vital clue

everybody else had missed. Then she shrugs and smiles that fractured smile as the uniformed cops head on in with their handcuffs and escort the guilty party out to the waiting car. Not so bumbling now, wouldn’t you say!

This whole trip is, in fact, one super-big investigation. A mission of non-stop note-taking and forensic examination. Every inedible English meal is photographed pristine before her. She finishes a bar of chocolate and presses the wrapper like a leaf between the pages of her book. It may be nothing but the apparent exotica of a foreign culture. But there is also the conviction that with sufficient vigilance and chocolate bar wrappers there might emerge a real and profound appreciation. Which may in turn lead to some critical point when the Answer is revealed and suddenly it all makes sense to her – maybe months off into the future, when she’s back in Japan.

To be honest, pretty much everything beyond the coach’s window seems alien to Yuki. The quality of light … the little houses … the fields in between. Even the glass through which she stares appears to be manufactured to European specifications – the rubber mouldings that hold the glass in place. The fabric on the seat before her … its density of colour … the depth of the fabric’s own fine fur. Even these tiny screws, Yuki thinks, at each corner of the plastic panel below the window are undeniably alien. You would never see a screw like that in Japan. And all at once she becomes conscious of the million individual parts that have come together in this coach’s construction, and imagines each

one slowly recalled to the place of its origin. She sees the screws begin to twist beneath the window. The plastic veneers peel away. Until suddenly the coach erupts into its near-infinite number of elements, which go twirling off and away to every part of the horizon. So that all that is left are the thirty-five Japanese travellers, their Tour Guide, Hana Kita, and Mr Thompson, their English Coach Driver. All thirty-seven of them standing on a moorland road, with their luggage stacked beside them, on a cold, grey English day.

*

Yukiko has been doing a fair amount of travelling lately. In her notebook somewhere she has made a list of all the tubes, trains, buses, taxis, etc. she’s recently occupied – the many and varied capsules that have shunted her about the place. Naturally, air travel remains the most exhilarating/disorienting – the one with the most potential for transcendence. If Yukiko had her way airline passengers would be obliged to wear something Futuristic. Ideally, something designed in the 1950s for how they imagined the twenty-first century would be. One day, she tells herself, she will create a figure-hugging jumpsuit in orange rayon and wear it on a regular domestic flight, without any hint of irony. Just to see how people react.

If she hadn’t been so busy studying Fashion, Yuki would very much have liked to train to be an Airport

Designer. She remains vaguely hopeful of someone approaching her regarding just such a position after coming across her sketches on the internet. If/when that happens she will just have to squeeze the extra work in at the weekends.

The fundamental mistake in airport design, Yuki believes, is that everything is so goddamned white. There is altogether too much light, both natural and artificial. The notion persists for some reason that, since the passengers are about to head skyward, a sense of space and whiteness is what’s required, to get everyone in the mood. But Yuki considers this to be a grave, grave error. In truth, the airport customer is preparing for a period of confinement, in what is essentially a fast-moving tunnel. One’s pre-flight, airport-bound hours are a process of surrender. We grow quiet. We withdraw into ourselves. And no wonder. We are about to pass through a portal. What’s required, Yuki feels, is warm, dark spaces. Something womb-like. Airports should, in fact, be underground.

Another of Yuki’s bugbears regarding modern-day airports – and one of the first things she will set about remedying once appointed – is having to travel the thirty or forty miles out to where the planes arrive/depart from the city after which the airport is named. Such a ridiculous waste of time. Yuki’s plan is to create a new generation of airports situated directly below the world’s major cities. Once the air traveller arrives at his/her destination and passes through immigration he/she will

simply step into an elevator and, moments later, stride out into: the Champs-Elysées, Times Square, Sydney Harbour, or the lobby of whatever hotel they happen to be staying in.

Sure, this will entail a good deal of digging, but Yuki believes that people are willing to rise to a challenge, particularly one with such evident benefits. She’s equally confident that there already exist large and noisy machines capable of doing the necessary earth-removal. If not, she is prepared to invent such a machine in any spare time she can conjure up between her regular job as a Leading Fashion House Designer and her weekend post creating a new generation of subterranean urban airports. She has already completed two or three rough sketches.

Most of the excavation will be spent creating the vast cavern necessary to house the airport. The tunnels/ corridors down which the aeroplanes will fly need not necessarily be that wide. Just big enough to accommodate a plane’s typical wingspan, plus an extra metre or two. But oh, yes – quite, quite long. At the point of entry Yuki envisages a sort of slash in the earth, somewhere just beyond the city’s perimeter. As the plane approaches its destination there is bound to be a little nervousness among the passengers. But people enjoy a tiny bit of nervousness now and again, don’t you think? The captain’s voice will come over the speakers: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, we are now approaching London Scar. Please fasten your seat belts, super-tight.’ Then – just imagine – dropping, dropping.

Peering out of the little windows to see the ground rising up to meet you. Children standing over their bicycles, open-mouthed. Then suddenly – POW! – the sky is gone, and the whole plane is swallowed up by Planet Earth and all you see are rocks and soil through the windows. And you are flying underground!

The coach starts to lurch and slow as it navigates the roads on the outskirts of a village. The passengers begin to look up. The chatter increases in tempo and volume. People are peering out in every direction. Yukiko thinks, If only there had been a Haworth International Airport. Imagine how much time and effort I could have saved myself over the last five days. Sure, I wouldn’t have spent four days in London with the sister I hadn’t seen in years. But I’d have been able to catch up with her later, most likely. Right now I’d be two hundred metres underground and heading for the elevator marked ‘Brontë Parsonage’.