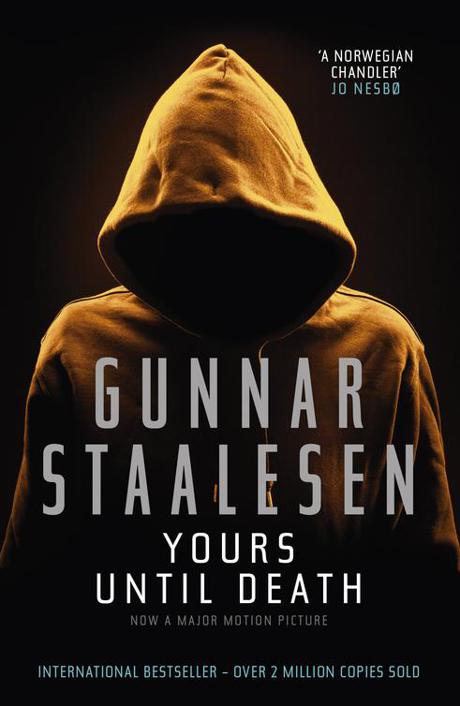

Yours Until Death

Authors: Gunnar Staalesen

PRAISE FOR GUNNAR STAALESEN

‘Undoubtedly, one of the finest Nordic novelists in the tradition of such masters as Henning Mankell’ Barry Forshaw,

Independent

‘The Varg Veum series stands alongside Connelly, Camilleri and others, who are among the very best modern exponents of the poetic yet tough detective story with strong, classic plots; a social conscience; and perfect pitch in terms of a sense of place’

Euro Crime

‘Hugely popular’

Irish Independent

‘Norway’s bestselling crime writer’

Guardian

‘The prolific, award-winning author is plotting to kill someone whose demise will devastate fans of noir-ish Nordic crime fiction worldwide’

Scotsman

‘Intriguing’

Time Out

‘An upmarket Philip Marlowe’ Maxim Jakubowski,

Bookseller

‘In the best tradition of sleuthery’

The Times

‘Among the most popular Norwegian crime writers’

Observer

‘Dazzling’

Aftenposten

‘Ice Marlowe’

Thriller

magazine

‘Gunnar Staalesen and his hero, Varg Veum, are stars’

L’Express

‘An excellent and unique series’

International Noir Fiction

GUNNAR STAALESEN

Translated from the Norwegian by

Margaret Amassian

Maybe it was because he was the youngest client I’d ever had. Maybe it was because he reminded me of another little boy in another part of Bergen. Or maybe it was because I had nothing else to do. Anyway, I listened to him.

It was one of those days at the end of February when the wind shoves the temperature up from minus eight to plus twelve. Twenty-four hours of unexpected rain had washed away the snow which had been lying around for three or four weeks, making a paradise of the hills around the city and a complete hell of its centre. But that was over. A breath of spring lay over the city now, and people hurried through the streets with new energy in their bodies towards destinations they could only guess at.

The office seemed unusually deserted on a day like this. The square room with its big desk and a phone, with the nearly empty filing cabinets, was like a little isolated corner of the universe, a place where they stash forgotten souls. People whose names nobody remembers any more. I’d had one call all day – from an old lady who’d wanted me to find her poodle. I’d said I was allergic to dogs – especially poodles. She’d sniffed and hung up. That’s how I am. Don’t sell myself cheap.

It was almost three when I heard somebody outside the waiting-room door. I was half asleep in my chair and the sound made me start. I swung my legs to the floor, got up and opened the door between the two rooms.

He stood in the exact middle of the floor, looking around curiously. He could have been about eight or nine. He was dressed in a worn-out blue ski jacket and jeans with patched knees. He wore a grey knitted cap, but when he saw me he yanked it off. His hair was long and straight and almost white. He had big blue eyes and a half-open anxious mouth which threatened to cry any minute.

‘Hello,’ I said.

He gulped and looked at me.

‘If you’re going to the dentist, it’s the office next door,’ I said.

He shook his head. ‘I want …’ he began, and nodded towards the door. In mirror-writing on the pebble-glass pane it said V. Veum, Private Investigator. He looked shyly at me. ‘Are you really a real detective?’

‘Maybe.’ I smiled at him. ‘Come in. Take a seat.’ We went into my office. I sat behind the desk and he settled himself in the other shabby chair. He looked around. I don’t know what he’d been expecting, but anyway he looked disappointed. It wasn’t the first time. Disappointing people is the only thing I’m really good at.

‘I found you in the phone book,’ he said. ‘Under Detective Bureaus.’ He pronounced the last word slowly and carefully, as if he’d invented it.

I looked at him. Thought: Thomas’ll be his age in a few years. And he’d also be able to find me in the phone book. If he wanted to.

‘And how can I help you?’ I said.

‘My bike,’ he said.

I nodded. ‘Your bike.’

I looked out of the window and across Vågen. The cars were bumper to bumper. It was stop-and-go all the way to

that far-off land they call Åsane, east of the sun and west of the moon. Which you reach – if you’re lucky – just in time to turn around, line up, and drive back into the city early next morning.

I’d had a bike once. But that was before they’d given the city to cars and had baptised it with exhaust. The smog was like a hood over the harbour. Mount Fløien looked like a poisoned rat lying on its belly, trying to suck in a little sea air. ‘Your bike’s been stolen?’

He nodded.

‘But don’t you think the police …?’ I said.

‘Yes, but that would cause trouble.’

‘Trouble?’

‘Yes. It would.’ He nodded. It was as if his whole face were filled with something he wanted to say but couldn’t find words for.

Then suddenly he became a pragmatist. ‘Do you charge a lot? Are you expensive?’

‘I’m the most expensive and the cheapest,’ I said.

He looked confused, and I added quickly, ‘It depends entirely on what kind of work and who’s hiring. On what you want me to do and who you are. Tell me about it. Okay, so your bike’s been stolen. And you want to know who did it and where it is?’

‘No. I know who’s got it.’

‘Really? Who?’

‘Joker and his gang. They want my mum.’

‘Your mother?’ I didn’t understand.

He looked very serious. ‘Listen, what’s your name?’ I said.

‘Roar.’

‘What else?’

‘Roar Andresen.’

‘And how old are you?’

‘Eight and a half.’

‘And where do you live?’

He named one of the bedroom suburbs southwest of the city, a place I wasn’t very familiar with. I’d only seen it from a distance. It had sort of reminded me of a lunar landscape, if they have high-rises on the moon.

‘And your mother – does she know where you are?’

‘No. She hadn’t come home when I left. I found your address in the phone book, and I took the bus all by myself, and I got here without asking anybody.’

‘We should try calling your mum so she won’t worry about you. Do you have a phone?’

‘Yes. But she won’t be home yet.’

‘But she works somewhere, doesn’t she? Maybe we could call her there?’

‘No. She’s probably on her way home by now. And anyway I’d just as soon she didn’t know anything about … this.’

Suddenly he seemed grown up. He seemed so grown up I thought I could ask the question on the tip of my tongue. Kids know so much more these days.

‘And your father – where’s he?’

His eyes widened. The only reaction. ‘He … he doesn’t live with us any more. He moved out. Mum says he’s got

somebody

else, even though she’s got two kids of her own. Mum says my dad’s no good. That I ought to forget him.’

I could see Thomas and Beate, and I had to say something in a hurry. ‘Listen. I think I’d better drive you home, and then we’ll see if we can’t find your bike. You can tell me the rest in the car.’

I put on my overcoat and took a last look around. One more day was about to die without having left any special trace behind it.

‘Aren’t you going to take your pistol?’ he said.

I looked at him. ‘My pistol?’

‘Yes. Your pistol.’

‘I don’t have a pistol, Roar.’

‘You don’t? But I thought …’

‘That’s only in films. TV. Not in real life.’

‘Oh.’ Now he looked really disappointed.

We left. The minute I locked the door, the phone rang. For a second I wondered if I should answer it, but it was probably only somebody who wanted me to find his cat, and it would probably stop ringing just as I got to my desk. Anyway, I was allergic to cats. So I let it go.

This was the one week in the month when the lift worked, and on the way down I said, ‘This Joker, as you call him – who is he?’

He looked seriously at me and his voice shook. ‘He’s … I can’t.’

I didn’t ask any more until we were in the car.

It was turning cold again. The frost clawed at the milky sky. The morning’s champagne fizz was gone. Not much hope in the eyes of those we passed: dinner, or problems at work. Or waiting at home. Winter played an encore, both in the air and in people’s faces.

I’d left my car at a meter up on Tårnplass. It stood there looking innocent, even though it knew that the meter had long since run out.

My little client had been glancing up at me the whole time, just as any eight-year-old glances up at his father when they’re in town together. The thing was, I wasn’t his father and not much to glance up at. I’m a private investigator in his

mid-thirties

, no wife, no son, no good friends, no steady partner. I’d have been a credit to the National Association for the

Advancement

of Singles, but they’d never asked me to join.

Anyway I had a car. It had survived one more winter and was on its way to turning eighteen. But it still ran, even though it had minor problems starting. Especially in choppy weather. We got in and were under way after a few minutes of my

hard-handed

diplomacy. Roar seemed impressed by my soundless cursing.

I’ve always been good at that. I almost never curse in front of women and children. Maybe that’s why nobody likes me.

Suddenly we got stuck in traffic in the middle of Puddefjord Bridge. It was like being on top of a fading rainbow. To our

right, Ask Island lay like a smear between the pale grey sky and the grey-black water. A thin veil of late afternoon light began to shimmer on the mountains.

To our left, at the very end of Viken, lay the skeleton of something which – if God and the shipping market willed it – would some day be a boat. A crane swung threateningly over the skeleton as if it were a prehistoric lizard just about to dine off a fallen dinosaur. It was one of those late winter afternoons with death in the air no matter where you looked.

‘Now tell me about your bicycle, and your mother, and about Joker and his gang,’ I said. ‘Tell me what I can do for you.’

I glanced at him and smiled. He tried to smile back, and I don’t know anything more heartbreaking than a little kid who tries to smile but can’t make it. This wasn’t going to be easy.

‘They took Petter’s bike last week.’ he said. ‘He doesn’t have a dad either.’

‘Oh?’

The traffic was slowly moving now. I automatically tailed the red brake-light ahead of me. He went on. ‘Joker and his gang they hang out – they have a hut up in the woods at the back of the high-rises.’

‘A hut?’

‘They didn’t build it. Somebody else did. But then Joker and them came and chased the others away. Nobody’ll go there now. Too scared to. But then …’

We were on the main road to Laksevåg. On the right, on the other side of Puddefjord, Nordnes looked like a dog’s paw lying in the water. ‘And then?’ I said.

‘We’d heard they’d done it before. That some of them took the big girls – grabbed them and took them up there to the hut

and … did things with them. But that was girls, not mothers. But then they stole Petter’s bike, and when Petter’s mother went up there to get his bike, then … then she didn’t come back down.’

‘She didn’t come back down?’

‘No. We waited at least two hours – Petter and Hans and I. And Petter cried and said they’d killed his mother and his father’d gone to sea and hadn’t ever come back, and …’

‘But didn’t you go – couldn’t you get hold of a grown-up?’

‘Who? What grown-up? Petter doesn’t have a father. Hans doesn’t. I don’t. And the caretaker chases us away and so does Officer Hauge, and that stupid youth leader just tells us we should come and play Parchese.

‘And then his mother came down again. From the woods. And she had the bike. But somebody had torn her clothes – and she was dirty, and she was crying. Everybody saw her. And Joker and the others followed her and they laughed. And when they saw us they said – so everybody could hear – they said if she said anything to anybody they’d cut off … that something bad would happen to Petter.’

‘But what happened after that?’

‘Nothing. Nobody’ll do anything to Joker and them. One time when Joker was alone, a girl’s father caught him outside the supermarket and shoved him up against the wall and said he’d beat him until he couldn’t stand up if he didn’t lay off.’

‘And?’

‘One evening he came home late, and they stood outside the door and waited for him. The whole gang. They beat him up and it was two weeks before he was okay. Afterwards he moved. So there’s nobody who has the guts.’

‘So I’m supposed to have the guts?’ I glanced at him.

He looked hopefully up at me. ‘You’re a detective.’

I let that sink in for a while. A big strong detective with little little muscles and a big big mouth. We were past the first

built-up

area and the fifty-kilometre limit, but I didn’t especially speed up. I felt less and less that we were in a hurry.

‘And now,’ I said, ‘so now they’ve got your bike, and now you’re afraid … Your mother, have you told her what

happened

to Petter’s mother?’

‘No! I was too scared to.’

‘And you’re sure that it’s Joker and his gang who –’

‘I’m sure! Because there’s a fat little kid they call Tasse, and he found me when I got home from school, and he told me Joker’d borrowed my bike and I could have it back if I went up to the hut. And if I didn’t have the guts, I could send my mother, he said. And he laughed.’

I said, ‘How many in this gang?’

‘Eight or nine. Sometimes ten.’

‘Just boys?’

‘They have some girls – but not always, not when they …’

‘How old are they?’

‘Oh, they’re old. Sixteen, seventeen. And Joker’s a little older. Some people say he’s over twenty, but he’s probably nineteen.’

Nineteen: a psycho’s best age. Too old to be a kid and too young to be an adult. I knew the type. Tough as a boot one minute and crying like a baby the next because you’ve hurt his feelings. As predictable as a day at the end of February. You never know how he’ll react. I had a lot to look forward to.