Young Men and Fire (16 page)

Read Young Men and Fire Online

Authors: Norman Maclean

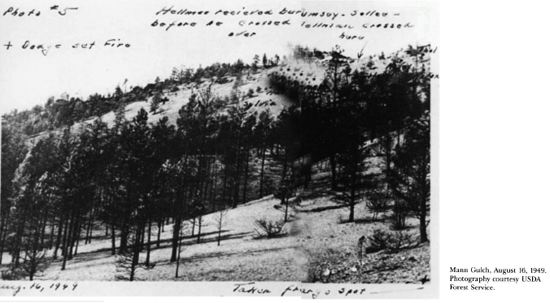

Accompanying the Smokejumpers on their August 5 flight was a Forest Service photographer named Elmer Bloom, who had been commissioned to make a training film for young jumpers; Bloom took shots of the crew suiting up and loading, of the Mann Gulch fire as it was first seen from the plane, and of what was to be the last jump for most of the crew. There are five frames from his documentary reproduced in

Life

, and for all my efforts to find the film, this is all I have ever seen of it. I did find an August 1949 letter from the regional forester in Missoula to the chief forester in Washington saying in effect that the film was too hot to handle at home so he was sending it along. Nobody in Washington can find it for me. I’m always told it must have been “misfiled,” and it may well have been, since there is no better way in this world to lose something forever than to misfile it in a big library.

It is hard to believe the film could be anything other than an odd little memento, but very early the threats of lawsuits from parents sounded in the distance and the Forest Service reversed its early policy of accommodating

Life’s

photographers to one of burying the photographs they already had.

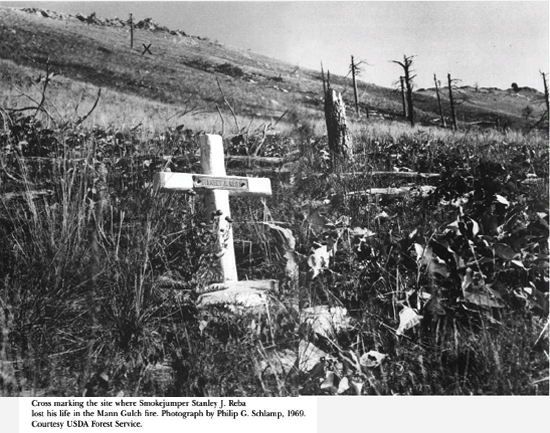

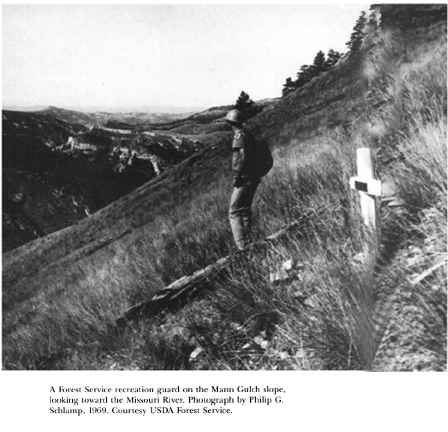

The leader of the public outcry against the Forest Service was Henry Thol, the grief-unbalanced father of Henry, Jr., whose cross is closest to the top of the Mann Gulch ridge. Not only was the father’s grief almost beyond restraint, but he, more than any other relative of the dead, should have known what he was talking about. He was a retired Forest Service ranger of the old school, and soon after the fire he was in Mann Gulch studying and pacing the tragedy. Harvey Jenson, the man in charge of the excursion boat taking tourists downriver from Hilger Landing to the mouth of Mann Gulch, became concerned about Thol’s conduct and the effect it was having on his tourist trade. His mildest statement: “Thol has

been very unreasonable about his remarks and has expressed his ideas very forcefully to boatloads of people going and coming from Mann Gulch as he rides back and forth on the passenger boat.”

The Forest Service moved quickly, probably too quickly, to make its official report and get its story of the fire to the public. It appointed a formal Board of Review, all from the Forest Service and none ranked below assistant regional forester, who assembled in Missoula on September 26, the next morning flew several loops around and across Mann Gulch, spent that afternoon going over the ground on foot, and during the next two days heard “all key witnesses” to the fire. The

Report of Board of Review

is dated September 29, 1949, three days after the committee members arrived in Missoula, and it is hard to see how in such a short time and so close to the event and in the intense heat of the public atmosphere a convincing analysis could be made of a small Custer Hill. In four days they assembled all the relevant facts, reviewed them, passed judgment on them, and wrote what they hoped was a closed book on the biggest tragedy the Smokejumpers had ever had.

In this narrative the

Report

and the testimony on which it was based have been referred to or quoted from a good many times, and an ending to this story has to involve an examination of the

Report’s

chief findings. But the immediate effect of the Forest Service’s official story of the fire was to add to its fuel.

By October 14, Michael (“Mike”) Mansfield, then a member of the House of Representatives and later to be the distinguished leader of the Democratic senators, pushed through Congress an amendment to the Federal Employees’ Compensation Act raising the burial allowance from two hundred dollars to four hundred dollars and making the amendment retroactive so it would apply to the dead of Mann Gulch.

The extra two hundred dollars per body for burial expenses did little to diminish the anger or personal grief. By 1951, eight damage suits had been brought by parents of those who had died in the fire, or by representatives of their

estates, “alleging negligence on the part of Forest Service officials and praying damages on account of the ‘loss of the comfort, society, and companionship’ of a son.” To keep things in their proper size, however, it should be added that the eight suits were filed by representatives of only four of the dead, each plaintiff bringing two suits, one on the plaintiff’s own behalf for loss of the son’s companionship and support, and the other on behalf of the dead son for the suffering the son had endured.

Henry Thol was the leader of this group and was to carry his own case to the court of appeals, so a good way to get a wide-angle view of the arguments and evidence these cases were to be built on is to examine Thol’s testimony before the Board of Review, at which he was the concluding witness.

Thol had become the main figure behind the lawsuits not just because he alone of all the parents of the dead was a lifelong woodsman and could meet the Forest Service on its own grounds. Geography increased his intensity: he lived in Kalispell, not far from the Missoula headquarters of Region One and the Smokejumper base. In addition, Kalispell was the town which had been Hellman’s home. Thol knew Hellman’s wife, and his grief for her in her pregnancy and bewildered financial condition only intensified his rage. There is also probably some truth in what Jansson told Dodge in a sympathetic letter written after the fire: Jansson says that Thol, like many old-time rangers, felt he had been pushed around by the college graduates who had taken over the Forest Service, so he was predisposed to find everything the modern Forest Service did wrong and in a way designed to make him suffer. In his testimony every major order the Forest Service gave the crew of Smokejumpers is denounced as an unpardonable error in woodsmanship—from jumping the crew on a fire in such rough and worthless country and in such abnormal heat and wind, to Dodge’s escape fire. The crew should not have been jumped but should have been returned to Missoula; as soon as Dodge saw the fire he should have led the crew straight uphill out of Mann Gulch instead of down it and so

dangerously paralleling the explosive fire; Dodge should not have wasted time going back to the cargo area with Harrison to have lunch; when Dodge saw that the fire had jumped the gulch and that the crew might soon be trapped by it, he should have headed straight for the top of the ridge instead of angling toward it; and so on to Dodge’s “escape” fire, which was the tragic trap, the trap from which his boy and none of the other twelve could escape.

The charge that weighed heaviest with both Thol and the Forest Service from the outset was the charge that Dodge’s fire, instead of being an escape fire, had cut off the crew’s escape and was the killer itself.

While the fire was still burning, the Forest Service was alarmed by the possibility that the Smokejumpers were burned by their own foreman. The initial committee of investigation appointed by the chief forester in Washington was headed by the Forest Service’s chief of fire control, C. A. Gustafson, who testified later that he had not wanted to talk to any of the survivors before seeing the fire himself because of certain fears about it which he wanted to face alone. In his words, this is what brought him into Mann Gulch on August 9. “The thing I was worried about was the effect of the escape fire on the possible escape of the men themselves.”

Jenson, the boatman who took tourists downriver to Mann Gulch, makes probably the most accurate recording of Thol’s opinion of Dodge’s fire. He said he had heard Thol say, “There is no question about it—Dodge’s fire burned the boys.” And the father didn’t blur his words before the Board of Review. “Indications on the ground show quite plainly that [Dodge’s] own fire caught up with some of the boys up there above him. His own fire prevented those below him from going to the top. The poor boys were caught—they had no escape.”

The Forest Service’s reply to this and other charges can be found in the conclusions of the

Report of Board of Review.

The twelfth and final conclusion of the

Report

is merely a summary of the conclusions that go before it: “It is the overall conclusion

of the Board that there is no evidence of disregard by those responsible for the jumper crew of the elements of risk which they are expected to take into account in placing jumper crews on fires.”

The Board also added a countercharge: the men would all have been saved if they had “heeded Dodge’s efforts to get them to go into the escape fire area” with him. Throughout the questioning there are more than hints that the Board of Review was trying to establish that a kind of insurrection occurred at Dodge’s fire led by someone believed to have said, as Dodge hollered at them to lie down in his fire, “To hell with that, I’m getting out of here!” As we have seen, there were even suggestions that the someone believed to have said this was Hellman and that, therefore, the race for the ridge was triggered by the second-in-command in defiance of his commander’s orders.

Rumors still circulate among old-time jumpers that there was bad feeling between Dodge, the foreman, and his second-in-command, Hellman, although I have never found any direct evidence to support such rumors. There seems somehow to be a linkage in our minds between the annihilation near the top of a hill of our finest troops and the charge that the second-in-command didn’t obey his leader because there had long been “bad blood between them.” Custer’s supporters explain Custer’s disaster by the charge that his second-in-command, Major Reno, hated the general and in the battle failed to support him, and it is easy to understand psychologically how a narrative device like this can become a fixed piece of history. It relieves “our” leader and all “our” men from the responsibility of having caused a national catastrophe, all except one of the favorite scapegoats in history, the “second guy.”