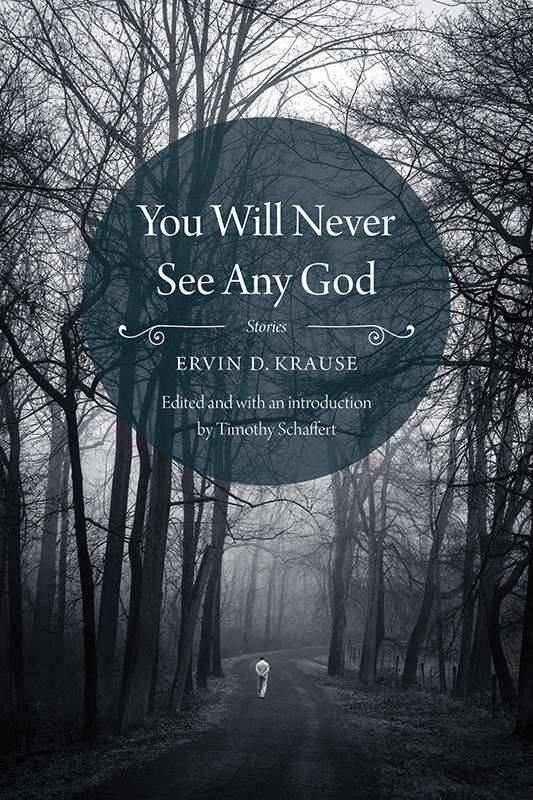

You Will Never See Any God: Stories

“To the rough South of Larry Brown, and the insular snarl of Daniel Woodrell’s Ozarks, add the austere plains of Ervin D. Krause. As hard, spare, and evocative as a prairie field in winter, the stories in this collection represent unearthed treasure, the important resurrection of an unflinching American voice. I’m lost in admiration.”

—Sean Doolittle, author of

The Cleanup

and

Lake Country

“Although there is not a single ghoul or specter to be found in the fiction of Ervin Krause, these sad, troubling stories will haunt you. He anatomized every part of us: our wicked wishes, our shameful, fears, and our tragic desires.”

—Owen King, author of

Double Feature: A Novel

“Krause is a brilliant and important writer without a book. His death at an early age cut short what surely would have been an important literary career. . . .

You Will Never See Any God

is both an act of rescue and a critical consideration of a body of work.”

—Hilda Raz, author of

What Happens

and former editor of

Prairie Schooner

You Will Never See Any God

Stories

Ervin D. Krause

Edited and with an introduction by Timothy Schaffert

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London

© 2014 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Publication of this volume was assisted by a grant from the Friends of the University of Nebraska Press.

“The Right Hand” is reprinted from

Prairie Schooner

33.1 (Spring 1959) by permission of the University of Nebraska Press, copyright 1959 by the University of Nebraska Press. “The Metal Sky” and “The Snake” are reprinted from

Prairie Schooner

35.2 (Summer 1961) by permission of the University of Nebraska Press, copyright 1961 by the University of Nebraska Press. “The Quick and the Dead” is reprinted from

Prairie Schooner

34.1 (Spring 1960) by permission of the University of Nebraska Press, copyright 1960 by the University of Nebraska Press.

Cover image from

stocksy.com

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Krause, Ervin D.

[Short stories. Selections]

You will never see any God: stories / Ervin D. Krause; edited and with an introduction by Timothy Schaffert.

pages cm

ISBN

978-0-8032-4976-9 (paper : alk. paper) —

ISBN

978-0-8032-5407-7 (pdf) —

ISBN

978-0-8032-5408-4 (epub) —

ISBN

978-0-8032-5409-1 (mobi)

I. Schaffert, Timothy. II. Title.

PS

3611.

R

3767

A

6 2014

813'.6—dc23

2013041641

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For Loretta

Acknowledgments

Over the years, Ervin Krause’s family and friends remained fiercely committed to the author’s memory and the work he left behind. We should all be so lucky to have such a devoted village of archivists. Most significant among them has been Loretta Krause, my dear friend and research partner. Loretta not only saved notebooks, drafts, and correspondence but has generously shared her memories of Ervin from their life together. I’m extremely grateful for Loretta’s kindness, humor, and spirit.

I’m also grateful for the time and attention that Marlene and Hank Krause have given to the project and the archives they’ve maintained—material that dates back to Ervin’s high school years. And it’s been a great pleasure to learn more about Ervin through his close friend and colleague Richard Goodman.

Special thanks to Kristen Elias Rowley of the University of Nebraska Press for her shepherding of this project. Ted Kooser has provided key perspective on the period and Karl Shapiro’s role in Ervin’s work. And many thanks to Susan Belasco for her support and encouragement.

Thanks also to Kurt Andersen, David Manderscheid, Judy

Slater, Wendy Katz, Kay Walter, Leta Powell Drake, Amber Antholz, Hilda Raz, Owen King, and Rhonda Sherman. And special thanks to Rodney Rahl for his insights and his enthusiasm for all my various literary endeavors.

This collection celebrates the tradition of the small literary journal and its decades-long commitment to the short-story writer. Some of the stories in this collection first appeared in

Prairie Schooner

(“The Right Hand,” “The Metal Sky,” “The Quick and the Dead,” “The Snake”) and

Northwest Review

(“The Shooters,” “The Witch”). The O. Henry Awards prize stories anthology reprinted “The Quick and the Dead” and “The Snake.” Other of Krause’s stories appeared in

University Review—Kansas City

,

Literary Review

,

New Letters

, and

College English

.

Introduction

In the stories of Ervin Krause, men and women are often unforgiving of each other’s trespasses. But their fiercest grudges are with the land and the sky. The characters are troubled by floods and parched earth, battered by “vivid, hurting” snow and intense summer sun. Sometimes nature wins in these struggles and sometimes humans do, but in Krause’s fiction it’s never a fair fight, and it’s often brutal.

In one of Krause’s most heart-wrenching and terrifying passages, in “The Metal Sky,” a farmer examines the intricate beauty and flight of a butterfly as he struggles to stay alive after an accident. Pinned, bleeding, beneath his own machinery, he seeks companionship in death while also envying the insect’s light-as-air indifference:

He brought his fingers up and then very carefully and quickly snapped the fingers shut on the arched yellow wings. The butterfly struggled, but its wings were caught and its fragile black body vibrated in its writhings. The yellow dust on the wings rubbed off and filtered down, lightly.

It will know I am not dead, the man thought. It alone, if nothing else, will know. He held the fragile wings of yellow light, with the wings so delicate he could not even feel them between his hardened hands. The butterfly tried to move and could not and the claws of its legs clasped the air.

Had Krause lived to write longer, to write more, we would almost certainly have come to have a sense of the

Krausian

—fiction characterized by the stark, haunting poetry of his language, the treachery of his landscapes, the moral and fatal failings of his unblessed characters. His stories are tantalizing portraits of sad hamlets surrounded by fields of failed crops and rising rivers, grim little worlds as gritty as the settings of pulp crime. These stories aren’t so much about survival as they are about the characters’ determination to outlive all the other hard-living men and women around them.

Though his stories are told without sentiment, with all of pulp’s electric tension and lack of mercy, they nonetheless have the gentle but insistent rhythms of folktale. There’s life, then there’s death. These are tales that command retelling; they’re cautionary, while inviting you to perversely delight in every character’s every reckless act. The stories play on our memories of shadowy figures and childhood fears, the countryside peopled with witches and skinflints, the nights prowled by wolves and scrutinized by an “agonized and lamenting” moon. And above all, a legendary bad luck plagues the characters’ minor lives.

“There was nothing dead that was ever beautiful,” considers the farmer of “The Metal Sky” in a last stab at philosophizing, as he perishes beneath a fallen tractor, unfound, unnoticed, in a field to which he has dedicated his life.

Some of this country squalor Krause knew by heart, having grown up in poverty, among tenant farmers. The Krauses moved

from plot to plot across Nebraska and Iowa in the years immediately following the Depression. Krause’s fiction depicts lives and fates he strove to avoid. His characters pontificate in saloons, condemning the morals of others as they slowly get sloshed; his men and women have extramarital affairs in old cars on winter nights; they traffic in gossip, terrorize their neighbors; they steal, they hunt, they spy. A child’s innocent curiosity can turn sinister in a minute—children see things too terrible too soon. These are stories of crimes big and small, with no law in sight.

While Krause’s characters contended with all sorts of demons, both within and without, Krause himself grew up under the strong moral guidance of Lutheran parents. Krause was born in Arlington, Nebraska, on June 22, 1931, to German Russian immigrants and grew up with four brothers. When he was fifteen, “his father fell paralyzed from a stroke,” writes Joseph Backus, a friend of Krause’s and an early devotee of his fiction, “to linger six years unable to speak, only listening as Erv would sit and read to him. But great purpose and principle drove the boys’ mother, who kept them in line with knuckle-thunks to the head or the tweak of an ear.”

Old Moder, as the boys’ mother was known, was not old at all. But stout and sturdy, her hair pulled back tight, she was an intimidating presence. She instilled in her young men a respect for education, but she seems also to have inspired a great sense of urgency—they studied hard, they went to college, they excelled in their professions. One son became an aeronautical engineer, one a professional baseball scout, one a doctor, one a farmer. Ervin proved both poetically and mechanically minded; a popular family legend has it that he was so expert in his high school science classes that the school never had to hire a substitute—

Krause readily stepped in to instruct whenever the teacher was out. While pursuing his bachelor’s degree in physics and math at Iowa State University, he contributed fiction and poetry to the school’s literary journal.

In between his bachelor’s degree and graduate school, Krause worked as a technical writer for MacDonald Aircraft in St. Louis and served eighteen months in the Air Force, stationed in England. Krause entered the master’s program in English at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln in 1956, the same year that poet Karl Shapiro took the reins of

Prairie Schooner

, the venerable literary quarterly that has been published by the English Department since its first issue in 1927.

Krause’s relationship with

Prairie Schooner

, and Shapiro’s mentorship, would rapidly advance Krause’s writing career, but it would also toss him into the center of controversy when his story “Anniversary” was declared “obscene” by the university’s dean of the College of Arts and Sciences—leading to an act of censorship that made national news.

As an editor, Shapiro showed a rigorous commitment to Krause’s work; “Anniversary” was to be the seventh story by Krause to appear in

Prairie Schooner

. The first, “Daphne,” was published in 1958. “The Quick and the Dead,” published in

Prairie Schooner

in 1960, was reprinted in

Prize Stories 1961: The O. Henry Awards

, along with stories by Tillie Olsen, Reynolds Price, Arthur Miller, Peter Taylor, and John Updike. In 1961 Shapiro promoted Krause’s work in a bold move: he featured three of Krause’s stories in the summer issue and boasted of it on the front cover with the same typographic fanfare he had previously allowed Walt Whitman and Henry Miller.

One of the three stories was “The Snake,” which went on to

become widely reprinted over the next several years and earned Krause another appearance in the O. Henry Awards anthology (alongside fiction by Terry Southern, Jessamyn West, Joyce Carol Oates, and Ellen Douglas). Textbook editors have proven particularly partial to “The Snake”—the story, with its brevity and efficiency and its powerful examination of cruelty and punishment, lends itself well to instruction in craft and analysis. Metaphor, motif, theme, allusion, conflict, foreshadowing, imagery—students of writing and literature can take the back off the clock and see how the cogs all click together. What lends the story its authority, however, is a bit more difficult to define. At the heart of it is a small act of passion on an ordinary morning of routine farm work, one that will likely change the relationship between the two characters—a boy and his uncle—for the rest of their lives.

By the time Krause’s story “Anniversary” was accepted for a 1963 edition of

Prairie Schooner

, Krause had moved to Honolulu, having taking a teaching job at the University of Hawaii. He was now married—at the University of Nebraska he had met Loretta Loose, who had spent a fast-paced year in a new master’s program in theater, performing role after role in the campus playhouse. Ervin and Loretta were young artists in love; they were married in 1961.

In Hawaii Krause taught creative writing and continued to write fiction and poetry—but his characters remained, determinedly, in the Midwest. According to Loretta, Ervin recognized the importance of place to a young writer seeking to establish an original voice. He knew the land and the life of the Midwest too well to ever finish with it, and he knew that such knowledge gave his work a necessary edge of authenticity. His notebooks—currently housed with his papers in the archives of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s Love Library—are riddled with sketches of characters and places, many drawn from his childhood on the plains.

The censored story, “Anniversary,” is one of only a few of Krause’s stories to be set in an actual city—and it’s this specificity that might have provoked the anxiety of university administrators. In “Anniversary” a character named McDonald returns to Lincoln, Nebraska, over holiday break to visit Wanda, a woman with whom he’d had an affair during his master’s program in an unnamed English department. McDonald, now an assistant professor of English at the University of Missouri, is a bit of a prig in the making. He’s a womanizer (the narrator provides insight into his sexism when the story describes the “birdy” female graduate students McDonald dated as having “unsexed bodies like store-window dummies and faces like parakeet beaks”), generally insensitive (the “fairies” in the department, we’re told, had approached McDonald “in sly, nuzzling, knee-touching familiarity”), and largely misanthropic (in a single sentence businessmen are “bland-faced” and sergeants are “gross-faced”). But he’s lonely, and desperately so, and “Anniversary” is easily Krause’s most chilling story.

McDonald’s emptiness contrasted with Wanda’s sweet nature and vulnerability further demonstrates an exploration of cruelty and frailty that so motivated Krause—most notably in his story “The Snake.” McDonald is even a writer himself and publishes his work in literary journals.

“Why do you write about such dark and unhappy things?” Wanda asks. “You should take things more lightly.”

Ultimately, McDonald convinces himself that Wanda is as dead inside as he is, and after lovemaking he confronts her with a sociopath’s disgust. All along, Krause articulates McDonald’s mean spirit in dark prose worthy of Richard Yates.

The prose proved too dark for university administrators, or the sex was described too explicitly. It’s unclear what most offended. Different stories abound regarding the true impulse to censor and how the story came to cross the desk of a dean not typically

involved in

Prairie Schooner

’s editorial processes. But Dr. Walter Millitzer, dean of the university’s College of Arts and Sciences at the time, took official responsibility. Millitzer removed the story from galleys without Karl Shapiro’s knowledge. Shapiro then publicized his immediate resignation from his editorship of

Prairie Schooner

and his intention to leave the university. He also read “Anniversary” on a local radio station. “Anniversary,” however, has never been published until now.

In an article in the

New York Times

dated May 24, 1963, Millitzer is quoted as describing the story as “obscene and in poor taste.” Shapiro, in the same article, defends the story as simply one of “washed out love with a couple of bedroom scenes.” The headline of the article indicated Shapiro’s response to the controversy: “Shapiro Quits Nebraska U.; Cites ‘Editorial Tampering.’”

Krause wrote to Clifford Hardin, the university’s chancellor, from Hawaii a few days after the censorship of his short story made the

New York Times

and other newspapers across the country: “The university must stand with fierce pride and integrity against the forces of ignorance and prejudice and stupidity; the university must defend the right of the artist to speak. You have denied what a university must stand for.”